In December, he withdrew his support for the Affordable and Secure Food Act that would have eased labor pressures on American farms by opening pathways to citizenship for farmworkers who have been in the country for at least 10 years.

An earlier version of the legislation had passed the House but failed to garner consideration in the fading weeks of last year.

A long list of groups representing farmers and farmworkers, who often don’t agree, had supported the bill. In the House, Idaho Rep. Mike Simpson voted for it, while Rep. Russ Fulcher opposed it.

Crapo had worked with Sen. Michael Bennet, D-Colorado to negotiate a bi-partisan bill but dropped his support for reasons he has refused to outline. His silence is a disservice to consumers and to his agricultural state. His withdrawal of support was a blow to worker-starved agricultural operations.

His website states, “Agriculture is a multi-billion-dollar industry in Idaho, and it is important for our farmers, ranchers, producers and growers that strong agriculture sector remain part of Idaho’s and America’s economy.”

Well, Senator? Knowing that it is not possible to have farms without farmworkers or to stabilize rising food prices when workers are scarce is not rocket science.

The bill would have extended the time foreign workers could work in agriculture in the U.S. Currently, they are allowed to work only in the spring and summer. Passage of the bill would have allowed year-round work. This would have helped farmers and farmworkers maintain healthy operations.

In the United States of America in 2023, picking your own produce is something Americans do for entertainment in the fall when pumpkin patches inspire afternoon jaunts to the country.

If Crapo and his colleagues don’t do something soon, pick-your-own or pack-your-own expeditions could become a necessity instead of a day’s outing.

Crapo is old enough to know that obtaining a gallon of milk wasn’t always just a matter of driving to a food market. Surely, not all of his ancestors were lawyers.

It took feeding and milking the family cow, separating the milk from the cream and packaging it—or having neighbors who did all of this. The cow itself needed pastureland, hay, a milking shed and veterinary care.

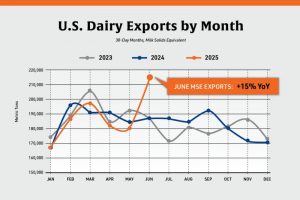

An industry spokesman illustrated the problem in 2022 when he told a state newspaper that it took one worker to care for 100 cows, but that farms could get only one worker for every 140 cows.

It’s easy to ignore the labor shortage as long as there is plenty of food on grocery shelves.

It’s going to get a lot harder when supplies get thin, when the romance of picking your own wears off, when dependence on foreign food products becomes dicey, when silence won’t cut it—and voters get hangry.