Wood Milk sounds like something you might find in the Goop catalog, or on Saturday Night Live, but it doesn’t actually exist. Rather, Plaza — acting in the commercial as a co-founder of Wood Milk — is mocking plant-based milks, the non-dairy varieties made from oats, almonds, soybeans, or coconuts.

Throughout the ad, Plaza hugs trees and dumps wood shavings on her head while espousing the supposed benefits of this “artisanal,” “old-fashioned,” “eco-friendly,” and “free-range” nectar of the forest. Wood Milk, like other non-cow milks, comes in various flavors: oak, cherry, maple, and mahogany.

“If you can’t pick your favorite [flavor], that’s okay, because they all taste like wood,” Plaza says in her trademark deadpan style. The implication is that non-dairy milks taste like, well, wood.

But the main point of the ad arrives at the end, when Plaza asks the camera in the same sarcastic style, “Is Wood Milk real? Absolutely not. Only real milk is real.” Black text on the screen reads “IS YOUR MILK REAL?” and the commercial ends with the iconic “got milk?” slogan. “Obviously, Wood Milk has zero nutritional value,” viewers are warned.

Plaza was mocking plant-based milk on behalf of the Milk Processor Education Program, or MilkPEP, the quasi-governmental dairy industry organization administered by the United States Department of Agriculture that ran the “got milk?” campaigns of the 1990s and 2000s.

While Plaza’s mock TV commercial is tongue-in-cheek, the dairy industry is serious about its message: Only milk from cows is “real.”

It’s an odd claim, given that people have been drinking milk from plants for centuries. But plant-based dairy and meat products have also been subject to industry attacks charging that they’re overly processed (another odd claim, considering the dizzying complexity of modern-day meat and milk production).

But the stakes of the milk wars go beyond mere aesthetics. While the Wood Milk commercial touts the “realness” of cow’s milk, it fails to mention the very real harms of dairy production: air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, inhumane treatment of cows, and dangerous conditions for a low-paid and vulnerable workforce, half of whom were immigrants in 2014, according to an industry survey. Shortly after the ad went live, Plaza was condemned for propagandizing for Big Dairy, and eventually turned off the comments section on her Instagram post about it.

Here’s a fact that is 100 percent real: Shifting some of our meat and dairy production to plant-based is critical to meeting climate targets, and doing so would reduce air and water pollution and prevent animal suffering. But that shift is made all the harder when the incumbent industry has an enormous advertising budget and immense power in Washington.

The backlash against plant-based milk and meat, explained

It’s safe to say that the millions of people who regularly drink plant-based milks don’t think it tastes like wood — otherwise the industry wouldn’t have grown fast enough to account for 16 percent of fluid milk sales. The product’s ascent into coffee shops and the dairy aisle has been swift enough to cause the conventional dairy sector to counterattack — US per capita dairy milk consumption fell by over 25 percent from the mid-90s, when “got milk?” ads began to take over the airwaves, to 2018.

The war of words over the authenticity of milk has escalated to the halls of Congress and statehouses in recent years — dairy groups have lobbied for legislation that bars plant-based milk companies from calling their products plant-based “milk,” “yogurt,” or “cheese.” The dairy industry, which spent $7.2 million on federal lobbying in 2022, argues that calling plant-based milk “milk” violates the US Food and Drug Administration’s “standards of identity,” which stipulate ingredient formulations for certain products.

For example, there are strict definitions that differentiate jelly, jam, and preserves, while “milk” is defined as “the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.”

The dairy industry has a point, but many commonly eaten foods have names that aren’t a perfect description of their contents. There’s no butter in peanut butter, for instance, or ham in hamburgers. (The latter name comes from Hamburg, Germany, home to the particular cut of beef that eventually went into hamburgers.)

Earlier this year, the FDA temporarily settled the matter when it issued draft guidance stating that plant-based companies can indeed call their products “milk,” but that the word must be preceded by what the milk is made of (e.g. oats). The National Milk Producers Federation called that part of the decision “unacceptable,” but the group was happy that the FDA at least recommended that plant-milk companies make voluntary statements on their packaging about how the nutrition of their product compares to that of cow’s milk.

The FDA hasn’t said when it may finalize its guidance, but wherever it lands, it probably won’t stop Big Dairy from provoking dairy-free companies with “real” versus “fake” messaging. That may appeal to our preference for what we think is the real thing, but it doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. It’s a perfect example of the naturalistic fallacy, which asserts that whatever is “natural” is good and real, and whatever is “unnatural” is bad and artificial.

The idea that one type of milk is real and the other isn’t is absurd on its face: Humans have produced and consumed milk from plants for centuries, which makes sense when you consider that over two-thirds of people, especially those of Asian, African, and South American descent, have difficulty digesting lactose, a sugar found in the milk of mammals.

The argument that plant-based meat and dairy are bad because they are highly processed is another fallacy that has gained traction in recent years. It’s disingenuous, and not because plant-based meat and dairy aren’t processed — they undergo a number of processes before they reach consumers — but so do animal-based foods.

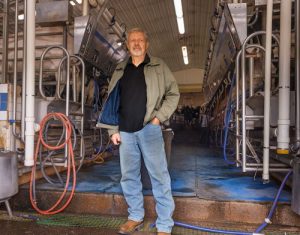

Let’s first look at how “real” dairy is made. Most milk comes from cows raised on large, industrialized farms in which they’re artificially inseminated and have their offspring removed from them shortly after birth. They go on to produce milk for a few years in massive barns where a couple times a day they’re hooked up to milking machines for 10 minutes at a time. The whole system hardly resembles the rolling green hills sometimes featured on milk and cheese labels (less than 20 percent of US dairy cows have access to pasture).

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24632607/GettyImages_629562447.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24632620/GettyImages_1482357105.jpg)

The cows’ milk is chilled, and then transported by truck to a factory where it’s tested for antibiotic residues before it’s pasteurized — heated to kill harmful bacteria — and then rapidly cooled. It’s also filtered to remove sediment and separate out some of the cream, which goes into producing creamer and other fat-heavy dairy products. Next, fat content is adjusted and, finally, the milk is homogenized, which entails forcing hot milk through tiny holes to break down oil droplets so as to ensure a smooth consistency. Dairy companies may add sugar, vitamins and minerals, or preservatives and emulsifiers, depending on how the milk will be consumed.

The cows, which have been bred to produce 2.5 times more milk than cows did 50 years ago, are killed at around three or four years old once their production has waned — far short of their “natural” lifespan of around 20 years.

The whole system is a far cry from the mental image we may have of milk production, and the one the industry sometimes evokes on its packaging and advertising: a farmer gently milking cows who were raised on pasture or in a big red barn.

And while there are many ethical problems in dairy production, the highly processed nature of dairy milk isn’t one of them. In fact, it’s necessary. If you’re trying to produce enough milk to feed 330 million Americans at a low cost, you have to do it on a large scale with the aid of technology to make it more efficient and safe. (Raw, unpasteurized milk may be more “natural,” but the FDA says it can pose a “serious health risk.”) The fact that dairy production entails a complex series of processes tells us little about how good or bad it is for us — or the environment and animals, for that matter.

The same goes for plant-based milk. Take oat milk, for example. Manufacturing methods vary, but generally it begins with taking oats that have been cleaned, peeled, and heat-treated and mixing them with water and enzymes that break down the oats’ starch. Oat bran, an insoluble fiber, is separated out. Plant oils are added for texture and gums are added as preservatives and thickeners. It’s filtered to remove solids, heat-treated to improve shelf life, and finally homogenized, just like cow’s milk. Producers may also add sugar, vitamins and minerals, and other additives.

Even better than the real thing?

Despite the highly processed nature of both plant- and animal-based foods, and the benefits derived from some of that processing, consumers keep falling for the fake versus real framing.

As Vox’s Kelsey Piper has written, this new generation of plant-based alternatives — especially alternatives to meat — were often praised by food writers as sustainable game-changers when they were produced in smaller batches and cooked up by trendy chefs. But as they landed on fast-food menus and were, by necessity, mass-produced, they were marked as “ultra-processed” foods of which consumers should steer clear.

To be fair, the plant-based industry can fall prey to the naturalistic fallacy as well, decrying GMOs and touting plant-based burgers that are “simple and clean” with “no synthetic ingredients, no artificial anything.” But the problem with processed foods isn’t that they’re processed, or how much they’re processed. It’s that sometimes the processing involves adding in a lot of addictive ingredients your doctor probably wants you to eat in moderation, like salt, sugar, and fat, which, of course, make those foods really difficult to eat in moderation.

The food writer Tamar Haspel of the Washington Post summed it up this way: “Processing is a tool, and, like any tool, it can be used for good or for evil. If I have a hammer, I can use it to fix my neighbor’s roof. Or I can kill his dog. Likewise food processing.”

NOVA, a classification system that sorts foods into four categories of processing — unprocessed/minimally processed, processed culinary ingredients, processed, and ultra-processed — puts plant-based alternative products in the latter category, along with Twinkies and soft drinks. Mark Messina, the director of nutrition science and research at the Soy Nutrition Institute Global, told Food Navigator that while food processing can impact nutrition, such categorization is “simplistic and does not adequately evaluate the nutritional attributes of meat and dairy alternatives based on soy.”

Instead of asking whether, or how much, a food is processed, we’d be better off simply looking at a food’s nutritional content. When it comes to plant-based milk, there’s a high degree of variability — soy milk is similar in fat, protein, and calcium to 2 percent cow’s milk, though other plant-based milks tend to have little protein. (It’s worth noting, though, that Americans already consume far more protein than the USDA recommends). Plant-based meat tends to have a similar amount of protein when compared to animal meat. As a plus, plant-based meats contain no cholesterol and typically less saturated fat, and are higher in fiber. But on the downside, they’re usually higher in sodium.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24632685/GettyImages_1319118145.jpg)

Ultimately, I wonder how much this mud-slinging and ingredient interrogation really matters. Americans love to say they hate processed foods, but our behavior in the grocery store and at the drive-thru belies that notion. “Ultra-processed food” accounted for 57 percent of our caloric intake in recent years (up from 53.5 percent in the early 2000s). Food corporations have created a culinary landscape in which added sugar, salt, and fat reign supreme; many plant-based meat and dairy companies are merely trying to fit into a world that Big Dairy and Big Meat have helped create. And given that every animal product replaced with a plant-based alternative reduces the toll of animal suffering and environmental degradation, that seems like a reasonable trade.

There’s room to criticize plant-based food producers for taking the route they have, but it’s a bit rich when it comes from the dairy industry, which partnered with Domino’s to create a pizza with 40 percent more cheese and with Taco Bell to create the creamer-based Mountain Dew Baja Blast Colada Freeze.

It’s unclear how many of the punches against plant-based food have landed. After years of record growth, plant-based meat and dairy sales have slowed, though it’s likely due to factors like cost, taste, and habit, rather than what celebrities are paid to think. But Big Dairy’s attempt to discredit plant-based milk could all be in vain, anyway; researchers say it has played only a small role in the decline of cow’s milk, which started decades before cow-free milk began to make a splash. The dairy industry’s real enemy, based on consumer trends, is bottled water, which indeed is minimally processed. And while it has no nutritional value, it also doesn’t include added sugar, fat, or salt.

Wood Water, anyone?