Counterfeits are the bane of the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium, which is now trialling tech in the rind.

When is a cheese not what it seems? When it’s a fake parmesan.

Italy’s renowned parmigiano reggiano, favoured for finishing off bowls of pasta and rocket salads, is one of the most counterfeited cheeses in the world. Now its manufacturers have found a new way to hit back against the lookalikes: by adding microchips.

The move is the latest innovation from the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium (PRC), the association which oversees production, which has been trying for a century to fight off cheaper imitations that do not follow the exacting requirements to make the real deal.

The cheese, which can trace its history back to the middle ages, gained the EU’s prized protected designation of origin (PDO) status in 1996. Under those rules parmigiano reggiano – the only kind which can be called parmesan within Europe – must be made in a small part of northern Italy, including in the provinces of Parma and Reggio Emilia.

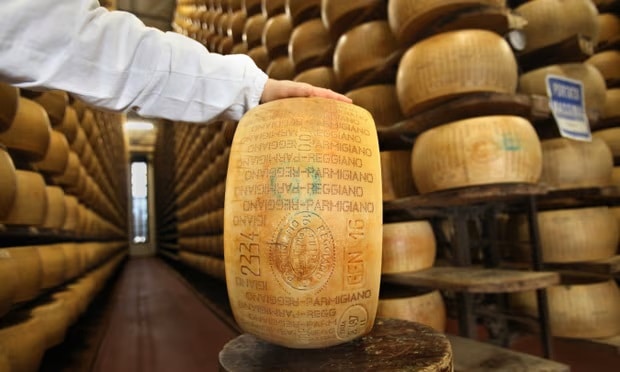

In addition, the wheels of cheese – which weigh on average 40kg (88lb) – have to be matured for at least 12 months in a mountain area, and are tested by experts two years after production to ensure they make the grade.

PDO status is given to foodstuffs “produced, processed and prepared in a given geographical area using recognised knowhow” and covers French champagne, Portuguese port and kalamata olive oil from Greece.

Given the strict rules in attaining the certification, such delicacies usually sell for higher prices, making it an enticing market for copycats. Indeed, the PRC estimates that annual global sales of counterfeit cheese reach about $2bn (£1.6bn), not far off those of the authentic product, which hit a record high of €2.9bn last year.

Now producers have been trialling the most modern of authentication methods – microtransponders about the size of a grain of salt inserted into the labels found on the rind of 120,000 wheels of parmigiano reggiano. The microchips are food-safe, but are unlikely to be eaten, given their location in the cheese’s hard skin, which is made from the milk protein casein.

The chips work as long-lasting, scannable food tags that allow consumers to track their product back to where it originated. Made by the US company p-Chip Corporation, they are embedded directly into a QR code label, and function like “tiny digital anchors for physical items”, according to the company.

“We keep fighting with new methods,” Alberto Pecorari, from the PRC, told the Wall Street Journal. “We won’t give up.”

The new way of tracing the cheese came about through a partnership between the PRC, p-Chip and Dutch/French cheesemark producers Kaasmerk Matec.

Despite billing itself as a “unique and inimitable cheese”, according to the PRC, the previous mark of origin has not been enough to fend off some counterfeits. Under that system all wheels of cheese – made from 550 litres of milk – carried a casein plate, featuring a unique and sequential alphanumeric code. Functioning as an ID card, the code made up a distinctive dot pattern running around the wheel, and included the month and year of production.

The new microchips are the latest stage in the cheese’s history, which dates back more than a thousand years to when it was devised by Benedictine and Cistercian monks looking for a long-lasting foodstuff.

Producers now believe new technology is needed, at a time when exports of parmesan to international markets are increasing, with just under half of last year’s production making its way beyond Italy’s borders.

The digitisation of the tracking process was designed to “convey the value of our product globally and distinguish it from similar-sounding products on the market that do not meet our strict requirements for production and area of origin,” PRC president Nicola Bertinelli has previously said.

The threat from knockoff varieties first raised its head after the first world war, when a South American imitation called reggianito appeared on the market, which had been created by Italian emigrants to Argentina.

Last year, the PRC was successful in blocking the US food giant Kraft Heinz from registering the “Kraft parmesan cheese” trademark in Ecuador, and hailed this as a notable victory, given that the EU’s PDO status is not recognised everywhere outside Europe.