Westland is the country’s second largest dairy co-op and if the Yili offer goes ahead, the country will have only two remaining co-ops — Fonterra and the Waikato-based Tatua Co-operative Dairy Company.

Westland chairman Pete Morrison said: “the board believes that the proposed transaction represents the best available outcome for our shareholders and has the unanimous support of the board.

The acquisition price represents an attractive price to the Westland shares’ nominal value.

Westland will seek shareholder approval for the proposed transaction at a special shareholder meeting which is expected to be held in early July 2019”.

Under a scheme of arrangement, the Yili acquisition must receive the approval of 75 per cent of shares voted as well as a simple majority of shares held by shareholders entitled to vote.

This co-op structure may be on its last legs as Westland’s and Fonterra’s performance illustrates that these farmer-owned structures are struggling in a highly competitive consumer market environment.

Dairy co-operatives have played a huge role in New Zealand.

An estimated 60 of them were operating in the late 1800s, rising to a peak of 500 in the 1920s. The benefits of economies of scale led to a raft of mergers including the amalgamation of the Westland Cool Storage and Dairy Company Limited, Kokatahi Co-operative and Waitaha Co-operative into the Hokitika based Westland Co-operative Dairy Company in 1937.

The Karamea Co-operative Dairy Company joined Westland in 1987.

By the late 1990s there were only four remaining dairy co-ops — Westland, Tatua, the New Zealand Dairy Group and Kiwi Co-operative Dairies. The latter two merged in 2001 to form Fonterra.

Westland stayed on its own as farmer-shareholders were determined to maintain their independence and have total control of their destiny.

This allowed the co-op to begin developing and marketing its own products under the Westland Milk Products brand name.

Westland is proud of its underdog status and during its 75-year anniversary in 2012 chairman Matt O’Regan said: “We are often billed as a David to the Goliath that is the dominant force in the New Zealand dairy industry.

In a way it is an apt metaphor, but it’s also worth remembering that by New Zealand standards we are pretty big in our own right.

“We might be a smaller player on the New Zealand dairy scene, but nationally we are in the top 100 New Zealand businesses by turnover, and we market to more than 70 customers in more than 40 different countries around the world”.

O’Regan went on to write: “The key reason for this success is that we have stuck with a truly co-operative model that has proven to be adaptable and resilient.

“The co-operative gives farmers the security of knowing their milk will always be processed, and they have direct access to the value that is added to their milk beyond the farm gate. As part of a co-operative, farmers have the market power rather than handing it to someone else down the value chain”.

These comments have been invalidated since then, as Westland has struggled to meet the aspirations of its farmer-shareholders.

Westland’s problems had already begun when the co-op held its 75th Jubilee celebrations in July 2012.

The co-op’s underlying problem is its lack of permanent capital, as shareholders can redeem equity when they cease supplying the co-op.

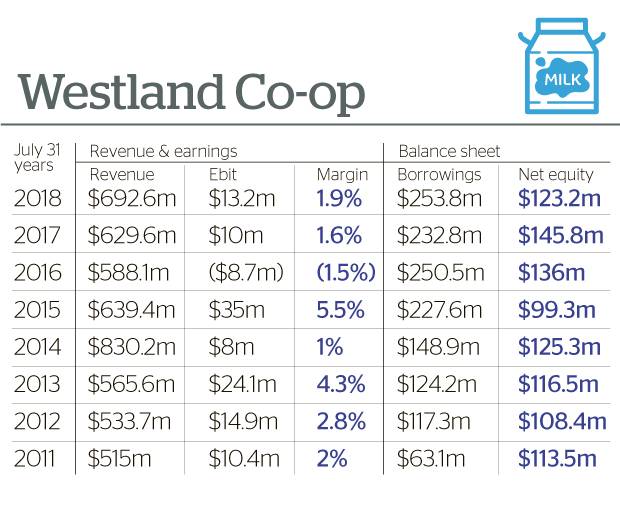

Because of this, Westland had to finance its expansions and developments through debt and its borrowings have increased dramatically since 2011 (see accompanying table).

In the four years ended July 2015, the co-op’s borrowings soared from $63.1 million to $227.6m while its net equity decreased from $113.5m to $99.3m.

The co-op reported Ebit (earnings before interest and tax) of $35.0m for the July 2015 year but that was only because it slashed its payment to farmers from $522.0m in the July 2014 year to $319.4m.

Nevertheless, chairman O’Regan wrote in the 2015 annual report: “Our co-operative structure presents a tremendous opportunity”.

The co-op’s 2016 result was a shocker, even though farmers took another huge haircut with milk purchases falling again, from $319.4m in the July 2015 year to only $264.2m.

O’Regan indicated a confusing attitude towards corporate governance with the following 2016 annual report comments: “Our growth strategies are strongly linked with the Westland approach of fostering direct engagement by directors and senior management with overseas customers.

“First-hand experiences gained from director and management visits to China and Europe proved invaluable”.

How could Westland even partially base its growth strategy on relationships between board members and foreign customers when it has had 24 different directors since 2009?

Pete Morrison, who replaced Matt O’Regan as chairman, wrote in the 2017 annual report: “With Westland finishing the 2015-16 year in the unenviable position of offering its shareholders the lowest payout of any New Zealand dairy company, we began the new financial year under considerable financial pressure”.

Morrison had the following capital review comments in the 2018 annual report: “However, full implementation of the strategy is likely to require significant new capital. The board is conscious we have relatively high debt levels and limited financial flexibility”.

The chairman’s 2018 report had an air of despondency and a few months later he announced that the board unanimously supported the purchase of the company by Mongolian based Yili.

Yili, which is listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, is China’s largest dairy producer with an estimated 22 per cent market share in its home country. Yili purchased Timaru-based Oceania Dairy in 2013.

Co-operatives have an inherent conflict between the desire of farmers to maximise their short-term milk revenue and the need for long-term investment in value-added products.

The high short-term milk payout argument usually wins and, as a result, dairy co-operatives have a strong focus on low-margin commodity products rather than high-value-added products.

This is illustrated by Westland’s Ebit margin of 1.9 per cent and Fonterra’s Ebit margin of 1.3 per cent for its July 2018 year.

By comparison, NZX-listed Synlait Milk and a2 Milk had Ebit margins of 12.9 per cent and 30.5 per cent for their 2017/18 financial years, although a2 Milk has a materially different business model from the other dairy companies.

Co-operatives that have evolved into limited liability companies are generally more profitable and more successful, as demonstrated by Kerry Group and Glanbia, two former Irish dairy co-ops now listed on the Dublin Stock Exchange.

Kerry Group has an Ebit margin of 10.4 per cent and a sharemarket value of €17.0 billion ($28.3b) while Glanbia has an Ebit margin of 11.9 per cent and a sharemarket value of €5.1b ($8.5b).

By comparison, Fonterra has a significantly lower Ebit margin and an effective sharemarket value of only $7.0b.

The big questions now are:

• Why did Westland borrow so much money and why didn’t it transform itself into a limited liability company long before directors were forced to recommend the sale of the co-op to overseas interests?

• Will Fonterra transform itself into an NZX-listed limited liability company before it is too late?

• If Fonterra doesn’t, will the country’s dairy sector end up in foreign control just as our banking, insurance, forestry and pulp & paper sectors have?

– Brian Gaynor is a director of Milford Asset Management which owns shares in a2 Milk and Synlait Milk.