He and his wife, Marcy, own Ed-Mar Dairy where they milk fewer than 60 cows on 130 acres of land. Even with diversification into cheese making and agri-tourism small farms like theirs are disappearing and replaced with mega facilities that can withstand the roller coaster effect of United States milk prices.

“For small farmers I don’t look for things long term to be very good.

Processors like semi loads of milk from one farm that is less than a day old,” he told an international tour group visiting his farm in mid May.

There is no support forthcoming from either government or consumers.

“From what I can see from the government, is they like cheap food. People like cheap food and bigger farms can make it cheaper,” he said.

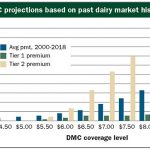

There are dairy support programs including a U.S. department of agriculture program where payments for eligible producers are available when the difference between the all milk price and the average feed costs falls below a certain dollar amount selected by the producer.

Nevertheless, the U.S. trend is moving toward larger, intensive farms with more than 10,000 cows in the western part of the country. Many of them are family owned but growth seemed like their best option to survive.

“They were in a part of the world where you could do it and the opportunity was there to do it. To keep ahead of everything they just kept growing,” he said.

He cannot expand by much because he does not have enough land to handle the manure.

His cost of production is escalating and milk prices have been in a slump for about four years.

He gets about $1.50 per gallon for his fluid milk at present but he has received less when he was paid $1.25 per gallon last summer.

That outlook has not stopped the family from trying new things.

Ed-Mar Dairy was the first in Kentucky to install a robotic milker. Rather than spending four hours a day in the milking parlour, there is time for other things, particularly a more rewarding family life.

The robot has improved production. The cows averaged 80 pounds of milk per day but now yield about 90 pounds. Rather than being milked twice a day, they visit about 3.5 times per day although Eddie suspects they are attracted to the grain offered as a treat while the robot does its job.

“I expected to have more free time with this than I do but I have a lot more flexibility in my schedule because I don’t have to be here at 5 o’clock in the morning and 5 o’clock in evening,” he said.

Marcy works off the farm as a dentist so Eddie handles most of the farm work. The robot allows more time for management and he can take over jobs that were once custom done. He grows his own corn silage, most of the hay and about half the grain he need. The cows also receive soybeans, corn ears and dried distillers grain from the state’s thriving bourbon industry.

Since the weather in this part of the country is hot and humid, the cows are turned outside at night when it is cooler to give them some grazing time. During the day they prefer to be inside the barn with fans and open sides for better air circulation.

The newest aspect of the farm business is agri-tourism.

“Milk prices have been so lousy and we were going farther into debt every day, so we started agri-tourism,” he said.

Eddie is a quiet person who wasn’t sure if he wanted visitors to the farm, but it turned into a positive experience with most of the business coming from school tours that are treated to a tour and a lesson about milk from Eddie and four volunteers.

They charge $10 each, which he thought was too much but realized many family activities cost much more. He prefers the younger students because they are more interested and enthusiastic about a field trip to a farm.

“We have done some high school students but they are hard to impress,” he said.

They became cheesemakers in 2013. Probably one day’s supply of milk per month is enough to make their branded cheese line. Their hard, English style cheeses have found a niche in smaller retailers, restaurants and online sales.

They received federal government matching grants to build that end of the business but it is not a gold mine. Processing, packaging and distribution all carves off a share before Gibsons see any profit.

The cheese is made from raw milk and under U.S. law it has to be aged at least 60 days. Most of their cheese is aged 120 days. The cheese is made offsite at a small batch creamery.

They have become part of the Kentucky Proud program that promotes local food production where their cheese is marketed as an artisan product. They are 20 minutes from downtown Cincinnati so the market reaches into northern Kentucky and southern Ohio where their cheese goes to butcher shops, wineries, restaurants and smaller retail outlets.

“We went gangbusters in the beginning and all the restaurants bought but we really have seen a decline in prices,” said marketing manager Rachel Wade.

Restaurants have also seen a decline in business so their purchases of cheese are often the first to be trimmed back. Restaurants and consumers may say they want local and artisan products but they do not always put their money where their mouth is.

“Everybody says they want it but nobody wants to pay for it,” said Rachel.

Large retailers are rarely interested in local cheeses so Gibsons signed on with a distributor called Local Food Connections that works with farmers offering artisan producers. Much of that product is sold online.

“No one in the local foods market, artisan foods or small farms is seeing a lot of profit,” she said.

Value adding is the future, said Eddie.

“Any outlets for the smaller guys is going to have to be something with value added,” he said.