Among those dairy farmers whose herds were affected are Valda and Terry Tout, Tamworth, NSW, and Rob and Jenni Marshall, Lardner, Vic. For the Touts, who exited the industry in 2017, a drug to treat Theileriosis comes too late. But they are hopeful for others.

Terry and Valda Tout did not know about Theileriosis before 2010. In the first six months of 2010, four cows died on their farm and various causes were suggested by government officials.

Finally, a private veterinarian took some blood tests and identified Theileria.

“NSW DPI had even autopsied a couple of cows, but did not identify Theileria,” Mr Tout said. “We thought it was milk fever originally.”

Dr Jade Hammer, a Bairnsdale veterinarian who is also a research associate with the University of Sydney, has made research into Theileriosis his focus for many years. He has confirmed the method of transmission is a parasite carried by ticks.

“Most farmers say there’s no ticks on their property, but we go out and find them,” he said. “Normally, the tick is on the animal for a brief period at night.

“While a large portion of the cattle do become infected and build up an immunity, a number of cows are at risk and – particularly around calving time when the animal is under stress – we do see the same dairy farmers year after year having outbreaks.”

The Touts lost 34 cows and 100 calves were aborted, with significant impact on their high performing herd.

The couple milked a 180-300 self-replacing closed Holstein herd producing 2.3 million litres of milk annually, operated two studs – Black and White Holsteins and Cowarol Holsteins – and were awarded Master Breeder status in 2006 by Holstein Australia. Their breed accolades included Supreme Intermediate Champion and Best Udder in the Holstein classes at International Dairy Week. They also won awards at the Brisbane and Sydney Royals and local shows.

“The cows affected worse by Theileria were fresh calved,” Mr Tout said. “Those close to calving were aborting. The cows that survived were sick then dry for 12 months.

“We had a high profile high genetic herd. One of our cows was rated in the top five genomically tested animals. We had cows in the herd valued at $20,000.

“Thirty of the cows that died were from the higher performing families. Half of the calves that were aborted were heifers. It set us back about four years in our plans.”

They chose to self-quarantine, didn’t attend shows and Mr Tout said he calculated a loss of $250,000 in milk production. The impact of the disease also put their expansion plans on hold, when they decided against buying an additional property.

“After the initial 18-24 months, we’d get about two cows a year die from it, until 2017. Because then we knew what signs and symptoms to look for,” Mr Tout said.

The veterinary bill was about $70,000 in the initial year, after they chose to test the blood of every cow in the herd. Mr Tout said he made a conservative estimate that $350,000 worth of cattle died.

A full line of the highest performing genomically tested cow family was lost to the disease. “You don’t get them back,” he said.

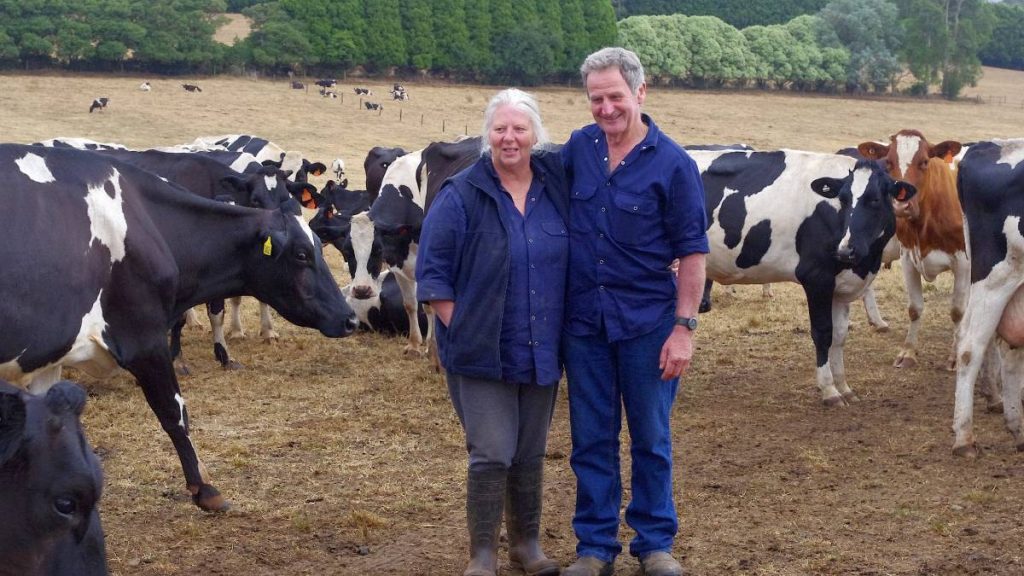

Lardner’s Rob Marshall saw 10 per cent of his 320-head self-replacing Friesian dairy herd affected by Theileria. Fortunately, after the first two cows died, he contacted his local veterinarian who was quick to test for and confirm the disease.

“We had cows getting sick. They were about four-to-six-weeks post-calving,” Mr Marshall said.

“They went from peak production to, for those that survived, being a dry cow by the next day. Within 36 hours of infection, a good cow will become a skinny cow. They are lethargic and don’t want to move.”

In all, 32 cows were infected in his herd and six cows died over a period of six months. There hasn’t been a recurrence of the disease since the initial outbreak in 2015.

But milk production dropped by 20 per cent – peak production is 1.8 million litres – and the dry cows had to be carried through until the next joining.