Rain, hail or shine, a worker rolls out of bed, dresses and sets out across the dark paddocks to bring the cows in.

Not long after, a second alarm goes off and another figure cuts a path through the inky blue pre-dawn, this one headed for the cowshed.

The lights flicker on and the machinery comes to life, awaiting the ‘milkers mob’, made up of cows that have calved and are producing milk.

By 5am long, low mooing and the clatter of hooves on concrete signals the mob’s arrival.

The first animals enter the shed and the workers settle into a rhythm honed over hundreds of milkings and thousands of hours, their movements fluid and precise.

The sky lightens as they work and when milking ends three hours later, the sun is shining on the 320-hectare farm.

It’s a welcome change from a run of wet weather and will make the day’s tasks easier on the staff, sharemilker Charlie McCaig says.

“Anyone can farm in the sun but it’s a different story in the wet – everything’s harder in bad weather,” he says.

Their first job done, the workers head home for breakfast. An hour later, they’re back and making the rounds of the ‘springers’, animals due to calve.

As well as collecting and recording the newborn calves, they check the condition of the cows and look for signs of any more impending arrivals.

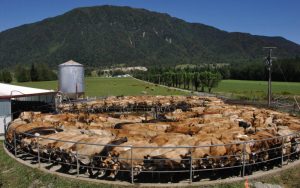

At the height of calving, up to 50 calves a day can be born on the 1000-cow farm, McCaig says.

While most calvings are straightforward, occasionally things get complicated, his wife, Jody, says.

“Calves are born like Superman, with their front legs up over their heads,” she says.

“Sometimes a leg will be back or the head can be twisted to the side and they need a bit of help.”

The springers are checked up to eight times a day, with Charlie usually making his final rounds about 8pm.

In between, the McCaigs and their staff feed out, set up fences, milk again, tend to the new arrivals and get ready for the next.

All the calves, including bobbies, are kept out of the elements in pens and fed regularly.

In their first days, feeding includes the ‘liquid gold’ produced by the farm’s most recent calvers, known as the ‘colostrum mob’.

“Calves don’t have good immunity when they’re born and colostrum is full of antibodies,” Charlie says.

The team uses a tool called a Brix spectrometer to measure the level of antibodies, giving the best quality colostrum to the newest calves.

“We’re trying to give them the best of everything and that includes colostrum.”

It’s one of many small tasks that make calving unlike any other time on the farm, Charlie says.

“It’s a really big change going from having all the cows dry to milking all of them.

“It’s like firing up a big factory after a shutdown – it can take a while to get all the systems back up and running.”

Communication is key to a smooth calving and the McCaigs sit down with their staff each morning to make a plan for the day.

Every now and then Mother Nature throws a spanner in the works and when things aren’t going well, the whole team feels it, Charlie says.

“There’s respect for the lives that you’re managing and if a cow is injured and has to be put down, it sucks. It’s the same with the calves.”

Their staff work on a six-on, two-off roster year-round but calving can still take a toll, Jody says.

“The fatigue is mental as well as physical and it’s really important that everyone gets that time off.

“We’ve been where they are now so we know what it’s like to do that grind,” she says.

“It’s not a normal job – there are things that have to be done, you can’t just leave them until the morning,” Charlie adds.

“But at the end of those long days, when you’re exhausted, you feel like you’ve really achieved something.

“You’ve done a good day’s work.”