The U.S. Farm Belt, already battered by low commodity prices, the trade war and mounting bankruptcies, is bracing for even worse times ahead.

Record flooding this spring across the Midwest and Great Plains damaged stockpiles of corn and soybeans in some areas, while the extremely wet weather led to widespread planting delays.

Now the threat of a weak fall harvest and the danger of an early frost could amplify hardship felt through stretches of Wisconsin and Minnesota and tip more family farms into bankruptcy.

“It’s going to be a tough year, there are no two ways about it,” said Steve Zenk, a farmer and farm advocate from Danube, Minnesota, a small town of less than 500 in the southern part of the state.

‘Holding our breath’

It was a soggy spring and cool, wet summer, which left crops in the area easily two to three weeks behind schedule in terms of maturity, according to Zenk.

Delays in getting the year’s crops into the ground have farmers and bankers keeping vigil over the harvest and approaching autumn.

“It gets cold this time of year,” Zenk told MarketWatch in a telephone interview. “We are kind of holding our breath, because an early frost could really damage crops.”

Corn, soybean and wheat crop progress across Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin has largely lagged behind five-year averages, according to the latest U.S. Department of Agriculture crop-progress reports.

Concerns about 2019 crops come as U.S. farm balance sheets already have been stretched thin by a handful of years of lower commodity prices. But early USDA forecasts for larger-than-expected corn production have contributed to pressure on prices while also drawing skepticism from producers and many analysts.

Weather-related worries had pushed corn futures C00, -0.55% to a five-year high above $4.50 a bushel in Chicago in June. On Wednesday, corn traded at $3.61 a bushel, after suffering a brutal August selloff. Soybean futures S00, -0.52% traded at $8.67 a bushel, after hitting a more-than-a-decade low earlier this year below $8 a bushel.

Wisconsin is the nation’s second-largest dairy producer after California, while Minnesota is also among the nation’s top dairy-producing states. While larger, industrial dairy farms may benefit from low crop prices that make it cheaper to feed cattle, family operations in states with shorter growing seasons often suffer.

“For the traditional dairy farmer growing their own crops, having low commodity prices is a bad thing,” said Pat Lunemann, a crop and dairy farmer with about 740 milking cows in Clarissa, Minnesota, in an interview.

Milk prices have risen in 2019, with September milk Class III futures DAU19, +0.16% trading at $18.20 a hundredweight Wednesday, marking a 9% year-to-date gain. Analysts have attributed gains in part to falling dairy cow inventories, which have contributed to slower growth in milk production.

Rising bankruptcies

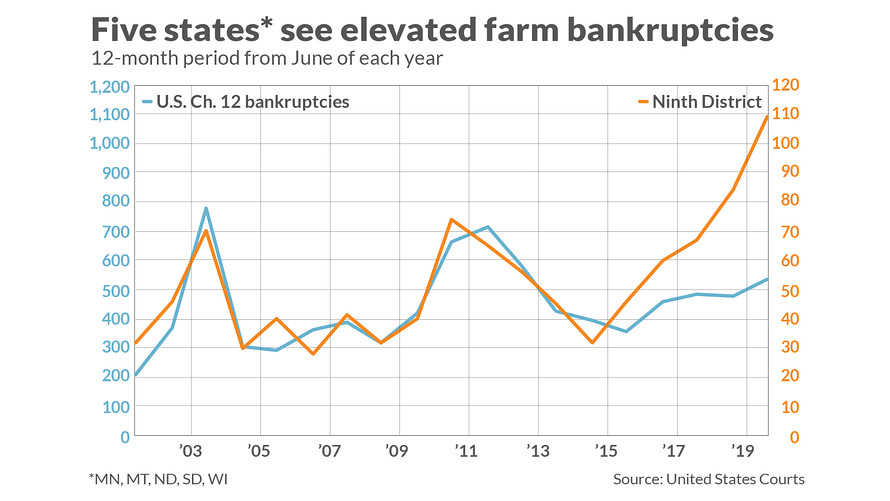

Meanwhile, farm bankruptcies in the Federal Reserve’s Ninth District, which covers Minnesota, Montana, North and South Dakota and Wisconsin, recently hit their highest level in nearly two decades.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

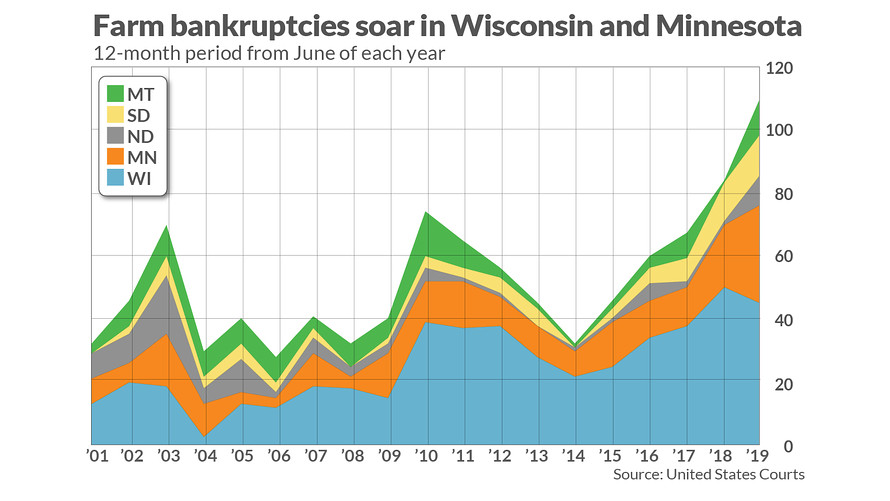

The chart below shows Wisconsin and Minnesota leading the Ninth District in chapter 12 filings, a special section of the bankruptcy code born out of the 1980s farm crisis to give farmers and fisherman ways to restructure their debt, while holding on to their businesses.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Joe Mahon, regional outreach director at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said the current farm landscape looks less bleak than during the farm crisis of the 1980s, mainly due to lower borrowing rates, less overall farm household debt and relatively stable land prices.

“Farms went into this slump with pretty built-up cash cushions,” Mahon told MarketWatch in a recent interview. “The concern is that the cash cushion has been worn down quite a bit. Not as many farms are positioned to withstand another year of low incomes.”

While bankruptcies have been a growing problem, Lunemann also said that many family-run dairies are calling it quits simply because they are burning equity and losing money. “At some point you say: enough is enough. I need to have something left over for retirement.”

Farm aid

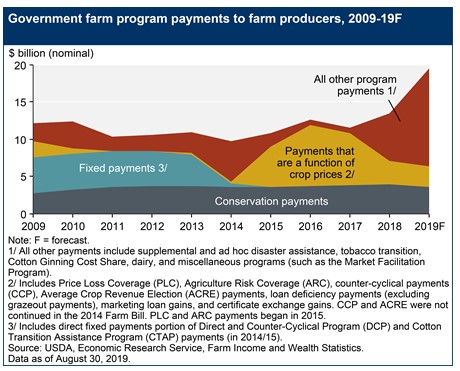

Meanwhile, farmers have needed to tap the lifeline of federal government aid programs, which the Trump administration recently bolstered in the face of its continuing U.S.-China trade war.

The USDA this year expects direct farm payouts from the government to reach a decade high of $19.5 billion, or double the payments seen in 2014.

USDA

Farm aid on the rise

“We are shipping practically nothing. We don’t have markets. We don’t have crops,” said farmer and farm advocate Ruth Ann Karty, of Clarkfield, Minnesota.

Since the 1980s, farm advocates have helped farmers in financial stress negotiate with lenders and apply for assistance programs, for free, including sometimes giving them a list of attorneys that handle chapter 12 proceedings. Farm Aid, started by musicians Willie Nelson, Neil Young and John Mellencamp, partners with national farm advocate programs.

Both Karty and Zenk said that bankers this fall were checking up on borrowers earlier in the season than usual about expectations for the 2019 harvest.

“It’s not an overwhelming number,” Zenk said of inquiries from bankers. “But we are seeing more than usual, pushing the issue of are you going to be short.”

Recent trade war escalations between Washington and Beijing, led China, the world’s largest buyer of soybeans, to close its doors last month to all U.S. farm products.

American Farm Bureau Federation President Zippy Duvall in August called the move a “body blow to thousands of farmers and ranchers who are already struggling to get by.” Farm Bureau estimates show that U.S. agriculture exports to China were down by $1.3 billion in the year’s first half, after dropping to $9.1 billion last year from $19.5 billion in 2017.

U.S. stocks moved higher Wednesday, a day after the S&P 500 index SPX, +0.72% and Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.85% closed at session highs following reports that China offered to buy more American agricultural products in exchange for a delay of coming tariffs.

“We would have had problems even without the trade war,” said Paul Mitchell, director of the Renk Agribusiness Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“A lot of farmers are baby boomers,” he said, adding that many older farmers are opting to retire early or sell before things get worse.

“They are being rational about what they want to do with their lives, and they don’t think the good times are coming back soon,” Mitchell said.