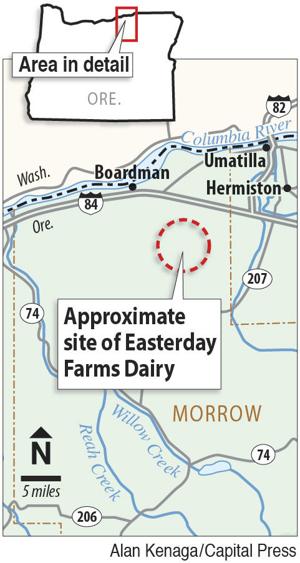

State regulators are drafting a Confined Animal Feeding Operation, or CAFO, permit for Easterday Farms Dairy near Boardman, which would have up to 28,300 cattle at full capacity.

The facility was originally developed as Lost Valley Farm by California dairyman Greg te Velde. It opened in 2017 with approval from the Oregon Department of Agriculture and Department of Environmental Quality, which jointly administer the state’s CAFO program.

Environmental groups at the time campaigned against the dairy, gathering more than 4,000 comments in opposition.

Almost immediately, Lost Valley began racking up numerous CAFO violations related to manure storage and handling. Te Velde later declared bankruptcy in September 2018, and lost control of his dairies — including two others he owned in California — amid allegations of drug use, gambling and money mismanagement.

Cleanup at Lost Valley fell to a federal trustee, who decided to sell the dairy. Easterday Farms, based in Pasco, Wash., bought the property at auction for $66.7 million in February and applied for a new CAFO permit on July 1.

Andrea Cantu-Schomas, a spokeswoman for ODA, said the agency is now working to draft the permit. ODA and DEQ must hold a public hearing within 35 days of notice before making their final decision. That date has not yet been announced.

Meanwhile, a coalition of 20 groups sent a letter Nov. 20 to Gov. Kate Brown, DEQ Director Richard Whitman and ODA Director Alexis Taylor urging them to reject Easterday Farms Dairy, saying it threatens to repeat the debacle of Lost Valley Farm.

“Lost Valley Farm showed us the state’s inability to regulate mega-dairies and keep the public safe from the environmental and health harms posted by these industrial-scale operations,” said Tarah Heinzen, senior attorney with Food & Water Action in Portland. “Industrial mega-dairies have proven too unsafe for Oregon, and the state should not grant Easterday’s — or any mega-dairy’s — permits.”

The groups argue that mega-dairies are significant sources of air pollution, including greenhouse gases such as methane, that undercut efforts to address climate change. They also write that mega-dairies put enormous strain on water supplies, drive family farms out of business and cram thousands of cows into concrete and metal barns.

“In 2016, we had significant concerns about the permitting of Lost Valley, each of which were validated as the ‘state-of-the-art’ facility was shut down within 18 months,” said Shari Sirkin, executive director of Friends of Family Farmers. “Now, three years later we have the very same concerns as yet another similarly sized mega-dairy seeks to set up shop in the exact same location.”

In a series of talking points about the Easterday Farms Dairy proposal, ODA says it will consider all comments during the public review. The previous CAFO permit for Lost Valley was “the most environmentally protective permit ODA ever issued,” and took two years to approve.

ODA says the real problem with Lost Valley centered on poor management.

“After more than 100 site visits, we have learned a lot about the issues on the farm and will be looking for the Easterdays to provide responsible management and other resources to achieve and maintain CAFO compliance,” the agency wrote.

Cody Easterday, president of Easterday Farms, previously said the company will invest $15 million in the dairy, including completion of a wastewater treatment system that was never finished before to bring the farm into full environmental compliance.

If approved, Easterday Farms Dairy will have 8,000 mature dairy cows and 2,650 dairy heifers housed under roof, along with 1,700 mature dairy cows and 5,950 heifers in open confinement. Another 10,000 cattle will also be kept on the property for beef production.

That would make it second in size only to nearby Threemile Canyon Farms, which has 68,340 cattle.

According to its CAFO application, Easterday Farms anticipates it will generate roughly 5.4 million cubic feet of liquid manure, 5.9 million cubic feet of solid manure and 11.7 million cubic feet of processed wastewater annually.

The nitrogen-rich manure will be stored in lagoons and recycled for fertilizer on 5,390 acres of surrounding farmland, growing crops such as potatoes, onions and forage for the cows.

Easterday said the farm has been reaching out to local communities to assure they have the management and experience needed to run the farm responsibly.

“It has everything to do with the operator,” Easterday said. “We’re a different operator.”