Wisconsin’s dairy industry is integral to the state’s identity, but the industry is struggling — and the threat of climate change hasn’t helped. Flooded fields, washed out roads and rising temperatures are making an already challenging job more difficult to manage. In this series, WPR is exploring how the state can adapt to and mitigate the affect climate change is having on some of Wisconsin’s most iconic foods.

On a cold, sunny day in December, a row of dairy cows chews through a precise mix that contains corn, alfalfa and soybeans at Crave Brothers Farm outside of Waterloo.

Those crops, grown on 3,000 acres of farmland, feed Crave Brothers’ 2,200 cows. In turn, the cows produce enough milk for the roughly 15,000 pounds of cheese coming out of the farm’s cheese factory each day.

“Our story is crops to cows, cheese to the consumer,” said George Crave, who runs the farm with his three brothers.

But there are costs to producing dairy products.

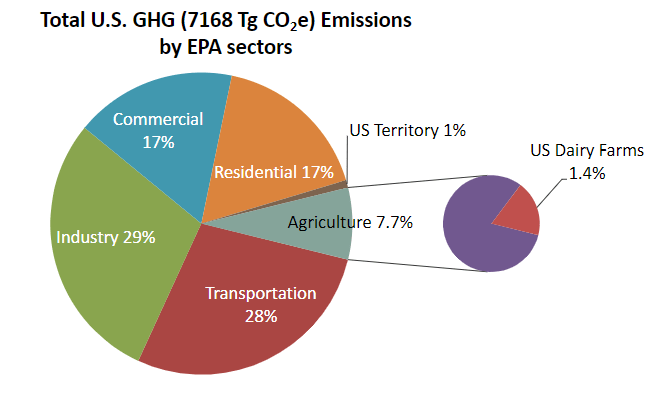

Dairy farms make a measurable contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. And globally, greenhouse gases from agriculture production create a vicious cycle — a hotter planet makes food production more difficult in many places.

Farmers like the Craves believe a farm that runs efficiently is ultimately better for the environment.

That’s one reason the Craves installed two anaerobic digesters — producing enough electricity for the farm, cheese factory and 300 homes in the community from the methane in cow manure, as well as fertilizer for the fields and bedding for the cows.

Recent years have been tough on dairy farmers — plummeting milk prices, oversupply and an overwhelming trend toward consolidation have led to a record number of bankruptcies across the state. Amid those struggles, climate change has emerged as yet another adversary. Wisconsin is a warmer and wetter place than it was a generation ago, and will continue to be so.

Experts say the agriculture industry needs to fundamentally change to mitigate and adapt to a changing climate. But dairy farmers, in an industry that is already stressed at the seams, have questions on what that means — and who’s going to help them do it.

Increasing Temperatures Tough On Dairy Cows

It takes a lot of milk to produce cheese.

While it depends on the style of cheese, Mark Johnson, assistant director of the Center for Dairy Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said it averages to about 10 pounds of milk for 1 pound of cheese.

But as the state warms, farmers are concerned about seeing their dairy cows produce less and less milk.

Cows like it cold and are particularly sensitive to heat stress, so every August and September there’s a dip in milk production, Johnson said. This could be problematic for cheesemakers who rely on milk that’s high in fat and protein.

Sarah Lloyd, a dairy farmer and director of special projects at Wisconsin Farmers Union, echoed Johnson’s concern, and added that summer nights don’t seem to cool off like they used to.

“It definitely reduces production,” she said. “You can see it immediately that day.”

Ninety percent of the milk produced in Wisconsin goes to making cheese. And while changes in tastes and lifestyles have led to a steady free fall in the consumption of drinking milk for decades, Americans are eating more cheese than ever before.

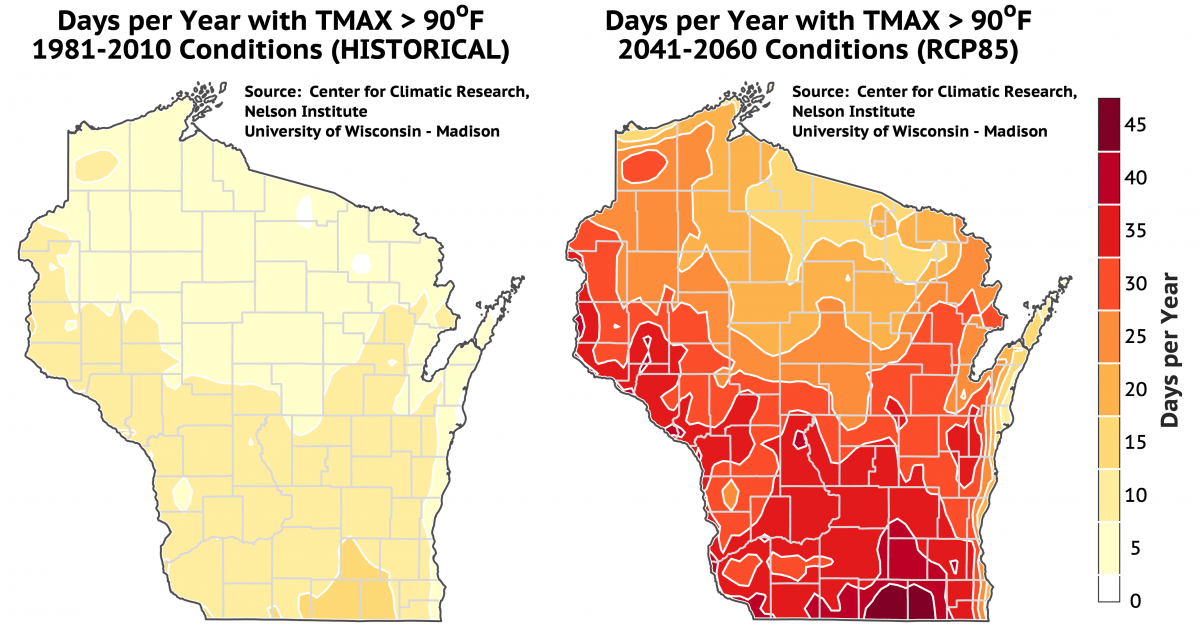

Since 1950, Wisconsin has warmed by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit. By 2050, scientists expect the state to warm by an additional 2 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit; the likelihood of greater frequency in heat waves will also rise.

A dairy cow’s optimal temperature range is between 25 and 65 degrees Fahrenheit — when temperatures reach 80 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, milk production can decrease by about 10 percent. Above 90 degrees, production can dramatically decrease, often by more than 25 percent, according to UW-Extension.

On Crave Brothers Farm, the cows are kept in open air, free-range barns designed to keep them comfortable and productive.

“If the temperature is over 75 degrees, they get water sprayed on them periodically, and we have large fans that continually cool them … keeps them eating, keeps them productive,” Crave said.

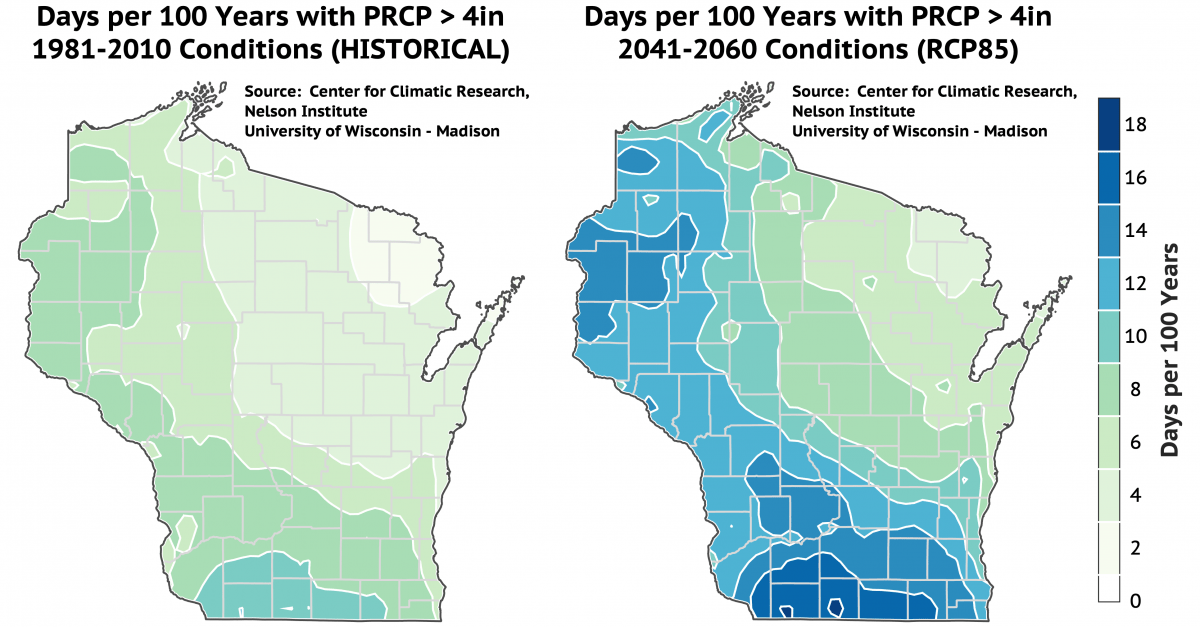

Out in the field, where the Craves grow the crops to feed their cattle like many other dairy farmers in the state, the last few years of intense rainfall have been tough on crop production.

‘The Ground Is Just Always Saturated’

There used to be dry-offs between rains, Crave said.

“But now it’s like, OK, here’s 2 more inches and there’s 2 more inches and there’s 2 more inches,” he said. “And all of a sudden in July, you get 7 inches. In August, you have 7 inches of rain, which is totally unheard of.”

“I can think of 2018, where I dumped 10 inches of rain out of the rain gauge in a one-week period,” Crave continued.

Yet, Crave considers his farm among the lucky ones. They’ve still been able to farm and work most of their ground — although he admits not very efficiently.

In other parts of the state — particularly in the western region — and the wider Midwest, so much rain has been devastating, delaying or altogether preventing crop plantings across the region.

Between disruptions to freeze and thaw cycles, dealing with washed out bridges and roads and increasing feed prices, farmers are feeling the pressure. The added unpredictability can be discouraging, but Crave said he’s not an alarmist.

“When Mother Nature really keeps stopping you from advancing, it’s frustrating for everyone,” he said. “It makes more work, and no one pays us for that extra work either.”

“When Mother Nature really keeps stopping you from advancing, it’s frustrating for everyone,” dairy farmer George Crave said. “It makes more work, and no one pays us for that extra work either.”

2019 was the wettest year on record in Wisconsin, and the 2010s went down as the wettest decade on record by a large amount, said Dan Vimont, director of the UW-Madison Nelson Institute Center for Climatic Research.

“Boy, you look across Wisconsin this summer, it was shocking how much standing water there was,” he said.

If annual average precipitation keeps increasing at current rates — around 20 to 30 percent since the mid-20th century — it will be catastrophic, said Chris Kucharik, chair of the UW-Madison Agronomy Department.

“In the last 10 years, our average rainfall is pushing 40 inches,” Kucharik said “It’s to the point that a lot of the landscape can’t handle that.”

Consensus among climate models suggests Wisconsin will be closer to 10 to 15 percent wetter in coming decades — meaning dry years will likely be mixed in.

“The law of averages suggests, well, maybe the next 10 years we’re gonna be 10 inches below normal each year,” he said. “If we get to like averaging 50 inches a year, you’re going to start seeing lakes appear in places that they weren’t.”

Changing Risk

Adverse weather events are becoming more frequent and more extreme, often in different places at the same time, said Molly Jahn, a UW-Madison professor and leader of Jahn Research Group, which researches risk in food systems.

And that’s challenging risk management and responses to natural disasters.

Farm credit services exist to cushion the risk farmers face, but as weather patterns are changing so are the risks they face — and there are concerns that risk profiles aren’t adapting as quickly as patterns are changing, she said.

“The whole system is affected in ways that intersect,” Jahn said. “A connects to B to C, etc.”

“But we frequently don’t think about the risks as intersecting,” she continued. “We have historically separated them and assess the likelihood of each one.”

Risks from events like flooding and drought can be pooled, Jahn said. And she expects there will be innovative risk mitigation measures going forward that come from a variety of stakeholders, such as insurance companies.

“Insurance isn’t the only solution, but insurance can provoke a set of actions or can organize,” she said. “Because ultimately … if we link capital to good behavior, we will see good behavior.”

A Low-Tech Vs. High-Tech Response

A thick cloud of steam pumping into the sky is immediately visible at Crave Brothers Farm. That steam is a byproduct of the two 750,000 gallon anaerobic digesters that capture the methane — a greenhouse gas 25 times stronger than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere — from manure and turns it into electricity.

Crave is frank that digesters aren’t a good, or economically viable, fit for all farms.

“Everything’s dependent on volume, efficiencies of size and scale. And it does take a lot of biomass or fuel, which in our case is the manure to power these,” he said. “There’s truly economic value to being certain sizes — and balanced in size, just getting bigger doesn’t guarantee anything.”

There are about three dozen digesters in Wisconsin. Farms have to be a sophisticated operation to make them work because they can take a fair amount of maintenance and capital, Jahn said.

Producing electricity alone isn’t enough to make the digesters worth the investment, Crave said. Electricity in the U.S. is cheap, so for digesters to make economic sense, they needed to find additional ways to add value through cow bedding and fertilizer.

Lloyd, of the Wisconsin Farmers Union, calls digesters a high-tech approach to climate change. On her family farm outside of the Wisconsin Dells — where they milk 400 cows — digesters don’t make sense because of the smaller size of their herd.

“That’s the risk, that you’re like, ‘Oh, don’t worry, technology will fix this,'” she said. “And it’s not to say that someone can’t come up with a technological fix. But then you just go back to that question of: who controls the technology, who has the money to access the technology?”

“The average dairy farmer right now is not that person,” she continued.

Lloyd is concerned solutions requiring a high amount of capital will only exacerbate the trend of consolidation and larger farms across the state.

“The risk is you devastate the small- and medium-scale producers … by not having the economy of scale, but they are creating a lot of other values,” she said.

While Lloyd considers anaerobic digesters a high-tech response, she calls rotational grazing the low-tech response.

Grazing is about making agriculture mimic the natural landscape as much as possible, said Randy Jackson, professor of agronomy at UW-Madison who leads Grassland 2.0, a recent USDA-funded project focused on transforming livestock agriculture from grain-based to perennial grass-based.

Perennial crops are a huge part of both adaptation and mitigation, he said. Perennial grasses improve the ability of soil to hold onto water, prevent erosion and runoff, and are much more resilient than row crops in the face of flooding.

“We’ve modified the grasslands and the wetlands and the forests so much that those modifications have basically cracked them open and made them leaky and made them unable to support biodiversity and do the things that we’d like them to do,” he said.

Jackson said all livestock raised for milk and meat production can be grazed.

But it’s not without challenges. Most obviously, grass doesn’t grow all year in Wisconsin. And if grazing isn’t managed properly — say, allowing cows to eat the grass down to a nub — it’ll undermine all of the environmental benefits.

“Management intensive rotation grazing is not your grandfather’s grazing,” Lloyd said. “It’s not like dumping your cows out to wander around, (it’s) much more like you’re a grass farmer.”

There’s also a productivity cost, grass-based milk and meat production provides lower yield than grain-based. But Jackson counters that studies show grazing is more profitable than confinement operations by reducing machine, production and feed costs.

“If we want to have something out on the landscape that’s more benign environmentally, that holds onto nutrients and carbon, we’re going to have to take a little bit less yield out of the landscape,” Jackson said.

“If we want to have something out on the landscape that’s more benign environmentally, that holds onto nutrients and carbon, we’re going to have to take a little bit less yield out of the landscape,” said Randy Jackson, a professor of agronomy at UW-Madison.

What Does It Mean To Be Sustainable?

Experts agree that agriculture needs to be a more resilient, less intensive system.

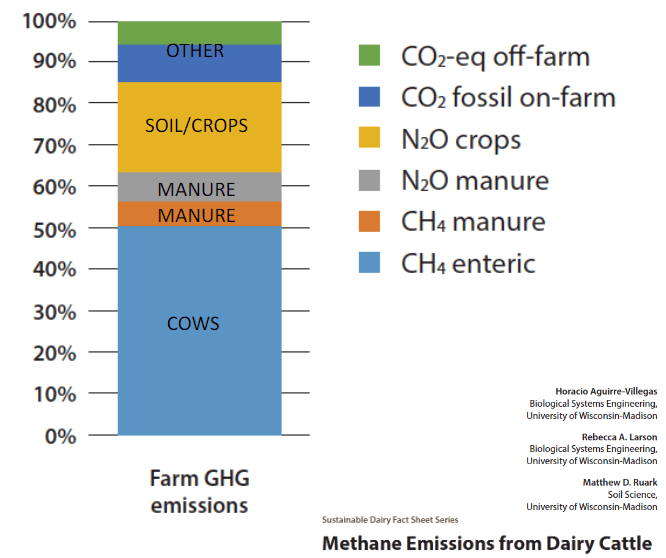

Globally, it’s estimated that about 25 to 30 percent of greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to agriculture. U.S. dairy farms are estimated to contribute about 1 to 2 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

Studies show dairy farms can significantly lower their emissions, while increasing profitability, through improving feeding strategies, cow genetics and manure management.

But the costs of making the changes to a more sustainable system can be out of reach for many farmers, and it’s left them wondering who will cover the cost, who’s responsible for what, and how they are supposed to get there.

“Right now, coming off of five years … of these low, low prices, it’s very difficult to imagine doing anything drastic that’s going to be risky or take investment into a new enterprise,” Lloyd said.

Yet Carol Barford, director of the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment, said that to feed a growing population on a limited amount of farmland, it’s far more efficient to feed people on plants than on animals.

The majority of corn grown in Wisconsin goes toward feeding livestock and producing ethanol. And corn as far as the eye can see is not a stable system, she said.

“We have to feed people, and if we want to do that and produce less greenhouse gas, we should feed people mostly on plants and not feed so many animals first … that’s a big change for a lot of people,” Barford said.

Back on his farm, Crave said contemporary farms like his often shoulder the blame for environmental problems because people have lost touch with where their food comes from, and who produces it.

“To say we’re not paying attention or we’re wasteful or that we don’t know what’s going on or that we don’t care is a misrepresentation of how we really run our businesses,” he said.