“I feel a little guilty,” she told the St. Paul Pioneer Press. “Actually, business is booming.”

She and husband Brian own KDE Farms in Hugo, a four-generation farm that, to their amazement, is thriving. Thanks to soaring demand for their beef, vegetables and pork, business has doubled in one year.

Most of the food industry is in crisis, with meat processing plants shuttered, prices rising and masks worn in every supermarket. Yet, family operations are enjoying a small-farm renaissance.

“It’s very exciting,” said Annie Klodd, a horticultural educator with the University of Minnesota Extension Service. “There is some kind of instinctual magnetism drawing people to locally produced food.”

That’s not what small farmers expected when the coronavirus stormed the nation in March. “They were asking, ‘How will we survive?’ ” Klodd said.

Owners of pick-your-own-fruit farms worried customers would stay home out of fear of infection or adherence to social distancing orders. “Exactly the opposite happened,” said Klodd.

Families saw picking their own food as a low-risk activity outside the home. “It’s naturally socially distant,” said Klodd.

Other small producers quickly learned their local meat and vegetables were perceived as healthier, and the local food rush began.

Suzy Chavie was so overwhelmed with customers that she went undercover — removing the only roadside sign for her Hastings farm. Now, no one drops in unannounced to the River Bluff Organic Farm, sniffing around for tomatoes or eggs.

Chavie produces food for six families on her five-acre farm. “I have 50 varieties of vegetables, from arugula to zucchini,” she said.

“I think I have doubled my demand in three or four months.”

Has the virus changed what people eat?

“I used to hear, ‘We do not do mustard greens in this family,’ ” said Chavie.

Now, customers are more nutrition-conscious and willing to experiment.

“That is really smart,” said Chavie. “The more you feed your body good food, the tougher you are against the virus.”

Back in Hugo, 200-acre KDE Farms sells food through an online store. It launched, fortuitously, in February.

Roberta Ehret has noticed demand fluctuates depending on the news of the day.

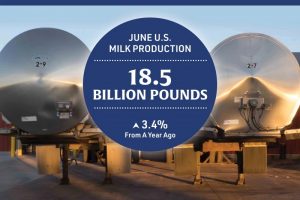

When supply chain interruptions push dairy farmers to dump milk they can’t sell and farmers are seen burning unharvested fields, KDE looks like an island of sanity.

In April, when local coronavirus outbreaks began shutting down meatpacking plants, “Our sales started to skyrocket,” co-owner Brian Ehret said.

KDE sells at local farmers markets and through a six-month subscription program within 20 miles of the farm.

On a recent Wednesday, Ehret was hauling his four portable, floorless chicken coops to different parts of his field. Instead of chemicals, he uses the “chicken tractors” for fertilizer, allowing the chickens to eat insects and enrich the soil with their droppings.

“I think lots of people have wanted to buy local but haven’t done it,” he said. “With this pandemic, now is the time to try it.”