Adams didn’t share the farm’s history at the time, but back in 1872, Charles Adams, a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania, had purchased the first parcel of land for $500. It had taken Charles years to find exactly what he wanted: An idyllic spot, crossed by a creek, with a knoll at its heart on which to build his home.

Over the decades, the farm yielded a variety of crops, hops first and later oats and timothy hay, as well as livestock like sheep, chickens, and cows. Mattresses were stuffed with feathers and corn husks. Since 1919 the farm has had both electricity and the same bathtub it has today.

Paul Adams bought the farm outright from his parents and, in 2002, started shipping organic milk after learning about keeping the soil healthy. Organic dairy cows have to get at least 30 percent of their food from grazing. And that means grass pastures.

“I can change the soil to be healthier, without chemicals,” Paul thought at the time. “And the organic market was already there [so] that I could reap a benefit. And for a while it made it possible to modify the soil to grow things healthier for the cows.” Nearing retirement, Paul and his wife planned to hand the farm down to their daughter.

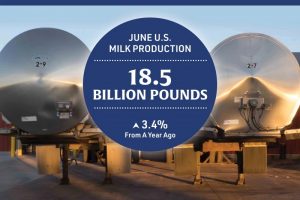

The rise of organic dairy had thrown a lifeline to America’s family dairy farms. Industrial dairies that had squeezed out the little guy couldn’t meet organic requirements like including lots of grass in their cows’ diets.

You can get a lot more milk out of your cows when you keep them in the barn eating grain, which just happens to increase milk production. But just try moving 10,000 of them two or three times a day from pasture to milking machines and back again.

Requirements like that made large-scale organic dairy farming look impossible. The little guys thought they were safe. But then, under both Presidents Bush and Obama, the big boys of industrial dairy began showing up in the organic markets. Somehow.

Paul told TYT that he had once had a contract with a bottler out east, but “all of a sudden [the bottler] could buy all the milk anybody wanted for $25 per hundredweight because of this milk coming on from large dairies that decided they could go organic. So they just flooded the market.”

With the plunge of organic milk prices, the bottler went broke in 2016, and Paul lost his customer.

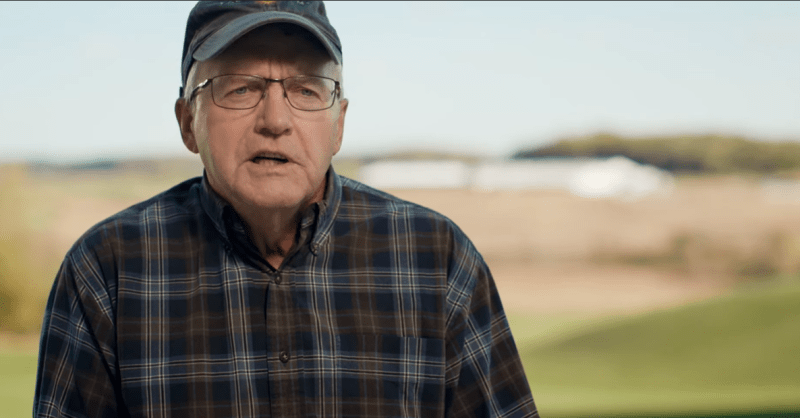

So, last October, Paul went to the World Dairy Expo in Madison, where Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue took questions from farmers. Paul was first up.

In video posted by the Expo, Paul is heard telling Perdue about “large, out-of-state, mega, quote ‘organic’ dairies that seem to not have to apply the same requirements that I have to comply with.” Paul asks Perdue, “Why is the USDA allowing this?”

THE FARMER IN CHIEF

Sonny Perdue joined Trump’s cabinet with a biography that included both politics and farming. An avuncular figure with a penchant for brash speech, his pastimes range from flying to ethical skating.

Perdue’s nomination raised immediate concerns that he would favor big agriculture over small farmers. And although Perdue is no relation to the Perdue chicken dynasty, big agriculture has treated him like family.

We don’t know who backed Perdue’s first forays into politics. Their identities have been lost to posterity. In response to requests for Perdue’s earliest campaign-finance disclosures, Georgia’s secretary of state referred TYT to the state’s Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission, which referred TYT to Georgia’s secretary of state. The two agencies ultimately responded to TYT’s public-records request, saying neither has Perdue’s filings from his multiple campaigns for state legislature.

When he ran for governor in 2002, opposing incumbent Democrat Roy Barnes, Perdue wasn’t a massive magnet for big money. After Perdue’s historic upset, however, his now-ended campaign began to get big checks from the same big business interests who had backed Barnes just weeks before.

According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Perdue took in more than a million dollars from Barnes supporters in the two months after he won.

W.C. Bradley CEO Stephen Butler, for instance, gave Barnes $8000 during the 2002 campaign. Butler’s predecessor at W.C. Bradley, William B. Turner, gave Barnes $5000.

Then, on Dec. 19, 2002, more than a month after the votes had been counted, Butler, Turner, and a third W.C. Bradley executive wrote $6000 in checks to Governor-elect Perdue’s campaign. The next day, Turner kicked in another $5000 to help Perdue retire his campaign debt.

Although W.C. Bradley is best known today for its consumer goods, it has a storied history in Georgia. In 1917, Bradley’s daughter married D.A. Turner, whose family still runs the company.

Two years later, W.C. Bradley himself led an investor group to purchase Coca-Cola, and sat on the board for almost three decades, two of them as chairman. The company, and the Turners, remain tightly tied to Coca-Cola even today. Bradley and Turner were also behind the launch of a local bank known today as Synovus, a major shareholder of Coke.

Another Perdue donor, one full year after his victory, was Pres. Reagan’s former assistant secretary of state, William Ball, who donated $1000. Ball at the time was president of the National Soft Drink Association.

Today, Ball has his own lobbying firm, and lobbied on Coke’s behalf from 2010 through 2018, including lobbying the USDA after Perdue took over. Coke’s lobbying disclosure forms, including Ball’s, don’t specify whether the company has lobbied Perdue about organic issues, but the beverage giant’s lobbying has included dairy and labeling regulations.

W.C. Bradley, too, has kept its toe in farming. W.C. Bradley Farms reportedly operates one of Georgia’s largest certified organic farms, producing eggs, produce, and dairy products.

Perdue’s early donors include some of the nation’s leading organic brands. But if there’s no evidence that Perdue’s USDA has shown his backers any special lenience, there’s also no evidence that they need it.

According to the Cornucopia Institute, Perdue has virtually ignored the recommendations of the National Organic Standards Board, which lost power under Obama. Small farms are struggling, including producers of both organic and conventional milk. (One conventional dairy farmer, Randy Messelt, told TYT he would have considered going organic, but the conversion costs were just too high; his farm went under in 2018).

The “mega-organic” dairies that Paul Adams worried about, however, are doing fine, including the one whose name he couldn’t remember when speaking with Perdue. It was Natural Prairie Dairy Farms (NPDF), out of Texas.

NATURAL PRAIRIE

The article where Paul encountered Natural Prairie Dairy describes owners Donald and Cherie De Jong as a husband-and-wife team who moved from California to become dairy farmers with help from Donald’s dad and brother. After purchasing a 1000-cow dairy in 1989, the De Jongs built it into three dairies with 400 employees, and 21,000 cows; 14,000 of them organic.

Natural Prairie Dairy today touts itself as “one of the nation’s largest family-owned and operated organic dairies.”

What the article didn’t say, was that Donald had help from two of his brothers, who were also dairy farmers. In fact, the De Jong boys were third-generation dairy farmers, their father having started his own after immigrating from Holland.

(Another family of Dutch De Jongs founded the Hollandia Dairy in California back in 1950. Texas disclosure forms show that one of them donated $768.50 in 2002 to the political action committee formed by Donald’s dairy cooperative, Select Milk, but an NPDF spokesperson told TYT the two De Jong families are unrelated.)

But the issue Paul Adams had wasn’t the size of the Dutch family behind the desk, but the size of the herd out in the pasture — or not out in the pasture.

The USDA doesn’t say anywhere that big dairy farms can’t meet organic requirements. Because it’s so difficult to do, however, any big operation that succeeds can have trouble convincing skeptical small farmers that they’re innovative rather than dishonest.

Ironically, neither honest big farms nor skeptical little guys are helped by the certification system as it stands. Regulation has been seen as lax under presidents of both parties. And the inspectors that big farms rely on to vouch for them are often themselves compromised by suspicions of regulatory capture or conflicts of interest.

So much of the verification process is outsourced to the industry itself — or to political figures whose jobs depend on donations — that it’s difficult to identify genuinely independent third parties that don’t have entanglements with the farms they inspect. In the absence of independent, broadly trusted, third-party inspections, organic and animal-rights advocacy groups have filled the gap, targeting big organic farms.

In 2009, one of the suppliers of organic cattle for Natural Prairie was suspended for four years in 2009 from engaging in organic commerce, after allegations by Cornucopia that the supplier “laundered” non-organic cattle. Last year, the Kroger supermarket chain suspended Natural Prairie Dairy as a supplier in response to undercover videos alleging animal abuse.

The videos were released by the Animal Recovery Mission (ARM). And although it’s a common mistake to assume that organic certification means the animals frolic on bucolic fields under fluffy clouds, there are some overlaps between organic qualifications and animal quality of life.

In addition to allegations of abuse and cruelty, ARM’s report on Natural Prairie Dairy said that organic dairy cows “only [grazed] for about an hour a day.” The cows spend the rest of their days in “squalid…illegally overcrowded feces-ridden barns.”

In response to ARM’s report, the Puget Consumer Co-Op said it has been pushing the USDA to strengthen organic standards. In a statement last year, the De Jongs called the video “highly edited” and cited USDA findings that “herd health was good to excellent.”

The USDA ultimately cleared Natural Prairie, saying that two years of investigations “did not substantiate the complaints…that NPDF failed to comply with the USDA organic regulations for livestock living conditions, livestock healthcare, or pasture practice standards.”

When Cornucopia sought internal USDA records about Perdue’s oversight of Natural Prairie, however, the documents were massively redacted after the agency asked Natural Prairie which passages to treat as confidential business information.

Although the USDA redacted the name of the inspector who certified Natural Prairie Dairy’s organic status, we do know the institution they worked for. It was the Texas Dept. of Agriculture.

THE TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

The mission of the Texas Dept. of Agriculture explicitly includes helping state agricultural businesses compete with farms in other states. In fact, that’s its stated reason for providing organic-certification services.

Natural Prairie Dairy was first certified organic by the Texas Dept. of Agriculture in 2005, under then-Commissioner Susan Combs.

Like her successors in the position, which is an elected office, Combs had the support of the Texas Association of Dairymen (TAD). State records show that the industry group wrote checks to the three most recent commissioners.

TAD’s leadership over the years has included top officials from De Jong’s dairy cooperative, Select Milk. The current TAD board includes Select Milk’s chairman and second vice-chairman, De Jong’s brother.

Combs was Donald De Jong’s first political donation of record in Texas, getting $500 from Donald in early 2000, over a year after she won the commissioner’s job.

Current Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller began getting donations from TAD and the De Jongs almost 20 years ago, when he was still a state legislator. In 2005, he teamed up with another De Jong brother to pass a bill supported by the Texas Dairymen. All told, TAD has given Miller $52,500 in campaign contributions.

Donald and Cheri De Jong first wrote Miller a $500 check in 2002. Since then, the two have given Miller $18,250 more.

In a statement provided by the NPDF spokesman, the De Jongs said, “Like many Americans, we are active in politics and donate to political candidates who we think will do the best job…for everyone. We have never asked for any political favors and never expected to receive special treatment from any politician, either personally or for our business.”

In April 2016, a little over a year in office, Miller appointed Donald De Jong as the only dairy producer on the agency’s Organic Agricultural Industry Advisory Board. The board’s mission includes helping Texas organic producers compete with other states.

One way the agency helps them compete is with organic certification. “By offering Texas farmers this service,” the agency says, “those farmers can capture a larger share of the premium organic food market.”

Last year, however, even Perdue’s USDA claimed that Miller’s agency violated organic rules, barring the state agriculture department from certifying new livestock clients. Miller’s agency disputed the claims and agreed to a settlement that specified only “non-compliance.”

Mark Loeffler, a spokesperson for Miller, declined to comment on the De Jong donations. Asked about the USDA’s allegations, Loeffler said the state and federal agencies have worked “together to improve the program.” He also said he “would point out that to my knowledge it has no direct connection to any specific inspections of the De Jong facility or any other livestock operation inspected by TDA.”

The USDA’s exoneration of Natural Prairie Dairy relied on other inspections in addition to those by the Texas Dept. of Agriculture. One of them was conducted by the National Milk Producers Federation.

However, Donald De Jong is a past board member of the Federation. And its current board includes three members from the Select Milk dairy cooperative where De Jong is vice chairman and has served as treasurer for its political action committee.

(The assistant treasurer for Select Milk’s PAC has since lobbied for the group on issues such as repealing the Waters of the U.S. rule. Select Milk is one of the country’s largest dairy cooperatives, and partnered with Coca-Cola on a dairy venture called fairlife.)

NO RESPONSE

It turns out that Paul Adams, the Wisconsin farmer, got his question wrong. Natural Prairie Dairy didn’t get an exception from the USDA at all. As the De Jongs told TYT in their statment, “we consistently meet or exceed the organic standards established by federal, state and local law.”

Although they will not release some details of how they master the challenges of large-scale organic dairy, the De Jongs said, “[W]e do not use any herbicides, pesticides, or synthetic chemicals, and our cows roam freely, feeding on our lush organic grasses a minimum of 120 days a year.”

They also tout their innovations. One new system, created as part of a joint venture, tackles the problem of excess manure by converting it to water, ammonia, and fertilizer.

Paul Adams, meanwhile, is featured in new videos shot by the Biden campaign, endorsing Biden for president. Family farms like the Adams Dairy weren’t helped much by Trump farm subsidies, the vast majority of which went to big agricultural companies.

Paul says the Biden campaign didn’t discuss policy with him, and there’s no indication that a Biden administration would dramatically reform America’s organic regulations, either for consumers or to preserve the shrinking safe haven organic farmers have. (The campaign didn’t respond to TYT’s request for comment. A spokesperson for Obama Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, now a Biden surrogate on agriculture issues, said he was not immediately available for an interview.)

As for Trump, his agriculture secretary made some news at last year’s Expo. When asked whether family farms could survive, Perdue gave a pithy but honest assessment of the state of the industry: “In America, the big get bigger,” he said. “And the small go out.”

Before Perdue left the Expo, he encountered Paul Adams close up. Paul had used his phone to look up the name of the dairy he couldn’t remember.

“I…wrote it down and physically handed it to Perdue and said, ‘Here’s the name of the diary that you asked about at the meeting,’” Paul said. “He said nothing and I heard nothing. He took it, I put it in his hand…I had the information to contact me and the name of that dairy which I felt was out of compliance.”

The USDA did not respond to a series of questions from TYT, but emailed a statement pointing to reforms now under way under Perdue. One, the Strengthening Organic Enforcement rule, “strengthens oversight and enforcement of the production, handling, and sale of organic agricultural products.”

The statement also said the USDA is “working on completing” the Origin of Livestock rule, which “closes a loop hole in the organic dairy industry with regard to transitioning cattle.”

The USDA’s statement did not address Perdue’s past political donors, or last year’s exchange with Paul Adams. Neither man knew it when they met, but a family history written by Paul’s mother reveals that they share a historic connection.

Paul’s great-grandfather wasn’t just a Civil War veteran, he had enlisted in Company K, 25th Infantry, serving under Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman during his March to the Sea. One-hundred and 55 years after Georgia’s decimation during Sherman’s March, that state’s former governor heard a plea for help from the descendant of one of the Union Army soldiers responsible.

Perdue never responded to Paul Adams. But Perdue’s words have proved prophetic: The big got bigger and the small are getting out.

Natural Prairie Dairy is now expanding in Indiana, where it successfully fought off a lawsuit claiming it violated the Clean Water Act.

But Perdue’s reforms will come too late for Paul Adams. Four months after meeting Perdue, Paul sold off the first of his cows. The last one was gone by March 7.

The checks for the cattle went to a creditor. Facing bills for feed, seed, livestock bedding, and utilities, the Adams Dairy went into receivership. Paul sold off the farm equipment and filed for bankruptcy on Oct. 7.

Instead of taking over the farm, Paul’s daughter is now looking for work as a bookkeeper. Paul and his wife, he says, “will be fine, unless Trump destroys Social Security and retirement savings.”

Under the farm’s new owners, Paul says, he’s “pretty sure it will not be farmed organic.” The closing date for the sale of the farm is Nov. 10, one week after Election Day.