Cooperatives such as Organic Valley, the largest farmer-owned organic cooperative in the United States, have responded by allowing some farmers to increase production.

The cooperative says demand for organic milk has gone up across the country by 11.3% in the past 52 weeks, based on data from SPINS MULO, a multi-outlet tracking service, looking back from Nov. 29. Over the past 12 weeks, it’s grown by 8.4%.

The increase is encouraging news for the future of organic dairy farming in Vermont, said John Cleary, New England manager for Organic Valley Cooperative. “We do hope to bring on more farmers in Vermont in the future,” he said. Many farmers have gone organic to get a premium price.

Even a modest 5% to 7% increase in consumption “means we need quite a bit more milk,” Cleary said. He estimates that market demand could sustain about 50 more organic dairy farms in the next five to 10 years.

Organic dairy is an attractive option for farmers because it pays more than conventional milk. Right now, organic milk in Vermont is sold for $30 to $35 a hundredweight, and there’s an extra premium for grass-fed milk, which ranges from $35 to $40. Conventional dairy farmers get about half that much.

With organic milk, “that’s a price that farmers can make money, if you’re a good manager,” said Cleary.

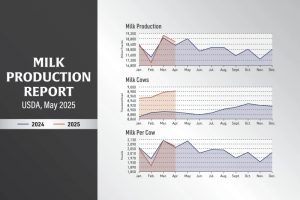

However, too much organic milk can cause a glut in the market and lead to a decrease in price, as happened in 2017. So, cooperatives have to coordinate carefully with the market.

While conventional dairy farms have been getting bigger in an effort to compete, organic dairies can do well on a smaller scale, and Cleary says that’s an opportunity for Vermont.

“A lot of other parts of the country don’t have the same number of small-scale dairies left,” he said.

Dairy farmers in Vermont have been grappling to find solid financial footing, and the pandemic made things worse. One casualty was Thomas Dairy in Rutland, a family business that closed in October after nearly 100 years in operation.

But while conventional milk lost the regular business they did with restaurants at the start of the governor’s stay-home order, organic dairy got a boost at a time when people were staying — and eating — at home more often.

Demand for retail grocery products has increased, while food service has gone down, as people are eating more meals at home and fewer meals out, said Elizabeth McMullen, a spokesperson for Organic Valley. E-commerce has also been affected, according to McMullen, and demand for single-service milk products has gone up.

“We have seen an impact in demand because of social distancing and more consumers eating at home. As more and more people look for healthy, quality ingredients, we have seen increased demand for our organic products,” McMullen said in a written statement.

“During stressful times, or for other reasons, maybe people are looking for healthy foods and foods that align with their values,” said Cleary, who made a presentation to the Citizens Advisory Council on Lake Champlain’s Future as it discussed the future of dairy farming in Vermont and its impact on water quality.

Longtime organic practices like cover-cropping are now being used by some conventional farmers to keep soil from eroding into nearby waterways; the practice keeps roots in the soil year-round.

And organic farms are held to other standards, like crop rotation and pasturing animals. Rotating crops keeps the soil healthy and able to hold more water, while pasturing animals allows manure to spread onto soil more gradually than liquid storage. So, more organic dairies could benefit the environment, keeping waters clean.

Maddie Kempner of the Northeast Organic Farming Association said Vermont producers report higher demand for organic food across all product categories, even beyond dairy.

“People are going more out of their way to seek out options that they feel are supporting their overall health and well-being at a time when that’s really, really necessary,” she said.

Kempner said too much of Vermont’s agricultural economy is based on dairy, and that poses a risk.

“I don’t think there’s any other state in the country who has as much of their farmland tied up in producing one commodity. So that’s an economic reality that we really need to look at and think about how to diversify, for our own food security and the future of that working landscape,” Kempner said.