In May, Phil Trowbridge, a farmer in Ghent, watched his first-ever virtual cattle auction with fear in the pit of his stomach.

“I was scared to death,” Trowbridge said. “All I was thinking was that I have to tell my wife we’ve got to sell the farm. How do you tell your kids that we were done?”

Trowbridge makes the majority of his family’s income from two cattle auctions a year. With COVID-19 prohibiting his usual in-person sales, he moved his event online and had to sell more bulls to make his usual revenue.

Bulls, of course, are both the product and a key element in the manufacturing line: “It was like selling part of our factory,” Trowbridge said, noting that this year will be even harder now that his herd is smaller.

To help farmers like Trowbridge financially endure a pandemic that upended agricultural markets, supply chains and labor practices, Congress created a special relief program through the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Trowbridge received a few thousand dollars in grant money, but most farmers in the U.S. were not so lucky.

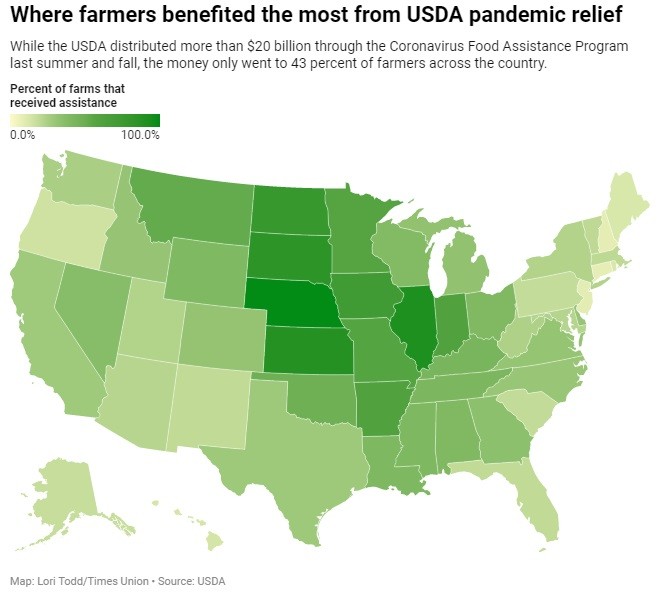

While the USDA distributed more than $20 billion through the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) last summer and fall, the money only went to 43 percent of farmers across the country, a Times Union investigation found.

The program was a major boon for Corn Belt farmers in the Midwest, but in 19 states, including New York, less than 25 percent of farmers received a payment.

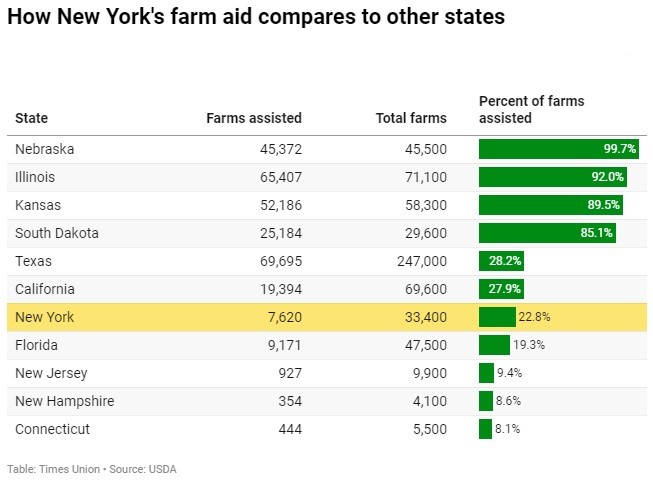

The numbers are glaring: In Nebraska, 99.7 percent of farmers received at least one CFAP payment, according to USDA data analyzed by the Times Union. In Connecticut, just 8 percent of farmers benefited.

In Illinois, 92 percent of farmers received a payment. In New Jersey and New Hampshire, just 9 percent of farmers benefited. In Kansas, 90 percent of farmers got money. In Maine and Rhode Island, just 13 percent did.

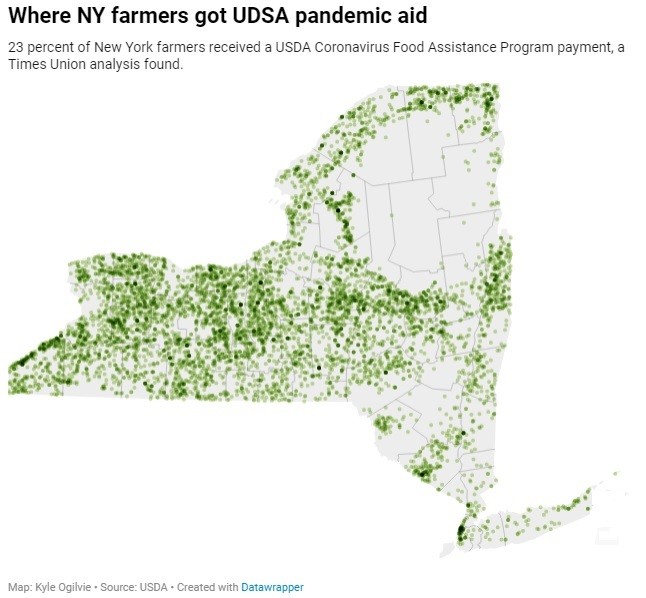

In New York, agriculture is a $6 billion industry with 33,400 farms, according to the USDA. But just 23 percent of Empire State farmers received a CFAP payment.

Other major agricultural states also saw small percentages of their farmers benefit: 19 percent of Florida farmers got a payment, along with 28 percent of farmers in California and Texas, and 34 percent in Georgia.

Asked about the numbers, the USDA said it had identified gaps and disparities in assistance both by the commodity being produced and by the type of production or farmer.

On March 24, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack announced changes to the program and plans for additional outreach to minority farmers, underserved producers, and smaller and medium-sized operations.

“The pandemic affected all of agriculture, but many farmers did not benefit from previous rounds of pandemic-related assistance,” Vilsack said. “The Biden-Harris administration is committed to helping as many producers as possible, as equitably as possible.”

Since the pandemic struck, Congress directed an unprecedented flood of federal aid to prop up American farms and the food systems they supply. In addition to the USDA relief program, the federal government took the unusual step of opening the Small Business Administration’s pandemic programs to agriculture businesses, although these programs are usually closed to farms.

A Times Union analysis found American farms have received over $23.8 billion in direct pandemic farm relief payments through CFAP and over $14 billion in Paycheck Protection Program loans.

Just as bigger, well-connected companies gobbled up large amounts of PPP loan money before Main Street shops could get in line last spring, the USDA program disproportionately favored certain types of farmers.

Until recently, CFAP favored row-crop producers – like corn farmers – and big operations that already had a relationship with the USDA, according to seven agriculture experts interviewed by the Times Union.

Many specialty crop producers – like fruit and vegetable growers – do not typically receive USDA subsidies and were initially left out of the program. When they were later added in September, some may not have known they were eligible.

“Entire segments were excluded, like biofuels; or even within livestock producers, there was no compensation for farmers that were forced to euthanize animals while processing facilities were closed,” the USDA told the Times Union.

“The sad reality is that, despite direction and resources from Congress, many of America’s family farms and specialty growers have been left to fend for themselves during this ongoing global public health crisis,” said U.S. Rep. Paul Tonko, D-Amsterdam. “Even as help poured into big corporate agricultural operations in the Midwest, small independent farms in New York and elsewhere were being overlooked. I raised this issue with USDA myself a few weeks ago to find out what went wrong and how they plan to fix it.”

For smaller farmers in particular, completing paperwork to attest for each row of onions or carrots was not worth the smaller payout compared to the hundreds of thousands of dollars received by large monoculture operations, experts said.

“People who do specialty crops or even dairy, traditionally there has been less money for them than anyone else,” said Anne Schechinger, a senior agriculture economics analyst for the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that specializes in agriculture research. “(An) apple grower might not even think this applies to you. Or the payment rate is so low that it’s not worth your time.”

USDA made some changes with a second round of the program that launched last fall, making more crop types eligible and simplifying the application process. But many small farmers and some farm types were still left out.

The USDA reached out to many farmers through their newsletters, emails and other announcements, as did other agricultural groups, but farmers who don’t usually have contact with the agency may have been less likely to hear about it.

In New York, about half of farms produce under $10,000 in sales and may not be involved in the USDA system, the New York Farm Bureau said.

“I guess I wasn’t even aware of it, to tell you the truth,” said Mike Nally, president of the Schenectady County Farm Bureau, who has a small cattle farm and raises honeybees in Glenville. He said he saw no outreach about the program, and based on what he did hear he didn’t think it applied to him.

“You see the word ‘grant’ and you say, ‘Yeah right – I can’t satisfy the grant,’” he said. “You see ‘loan’ and you say, ‘I can’t take more loans because I’ve got to pay them back.’ The whole COVID thing was I was going to hunker down and do the best I can.”

The pandemic had varying impacts across agriculture markets at various times. Early on, some dairy farmers were forced to dump milk and some farmers plowed crops under because COVID-19 disrupted their supply chains. With virus outbreaks at meat processing plants, some farmers struggled to get their livestock to market.

Produce, like apples and onions, that could be stored for a time fared better than items that had to go to market quickly after closures of schools and restaurants disrupted demand. Meanwhile, some farmers who sold through farm stands and other local means saw an uptick in demand from customers at home.

Many farmers had new costs — from personal protective equipment to extra marketing.

“It was pretty much across the board,” said New York Agriculture Commissioner Richard Ball of how the pandemic influenced farming in the state. “No one has escaped the impact of COVID-19.”

The objective of CFAP was to mitigate actual production and marketing losses. Farmers didn’t have to prove any personal losses to get a payment; they just needed to fit into a category that the USDA determined was eligible based on a variety of factors.

Farmers could get up to $250,000 in the first and second rounds of the program, while corporations could get up to $750,000 under certain conditions. You generally qualified if you made up to $900,000 a year in income. The payment was taxable.

Some smaller farmers said they did not apply although they were eligible because they personally had decent sales during the pandemic. Elizabeth Higgins, a business management specialist who works with fruit and vegetable growers at Cornell Cooperative Extension, said she had to coax some skeptical farmers to apply.

“I did have farmers who were saying they were having a very good year – so were soybean farmers in the Midwest, and they are lining right up (for aid). This program is not about whether you personally are having a good year,” Higgins said. “Commodity crop farmers are more used to that.”

In contrast, she added that she knew of farmers in the Midwest who made sure to maximize their CFAP payments by applying for each owner in their general partnership or jointly owned business to receive a payment – something permissible under the program’s rules in some circumstances.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS), a nonpartisan government entity that studied the program, reported to Congress that its implementation methodology failed to incentivize participation by all affected agricultural sectors and all injured producers in those sectors — in particular, among small farmers, processed food commodities and aquaculture producers.

Moreover, CRS found even after changes were made to the program, the USDA’s formulas and eligibility criteria resulted in producers of row crops like corn and soybeans receiving the largest share of the payments, a share that greatly exceeds their average national output value.

In New York, dairy farmers received the most benefit from CFAP by far, followed by corn and cattle in round one of the program, according to a data dashboard compiled by the USDA. In round two, less money flowed to New York dairy farmers, while sales commodities – like fruit and vegetables and aquaculture – edged into second place for funding, the USDA’s dashboard shows.

In New York, the Times Union found that the farmers left out of the program — more than 25,000 — fit a few profiles. The state is home to thousands of small family farm operations, which may not have been eligible due to their commodity type or may have been less likely to hear about the program or know they could apply.

New York is also home to thousands of horse farms and breeders, who were not eligible for the relief program.

“The equine community is isolated in many ways from all of these programs,” said Marion Gaigal, owner of a Morgan horse breeding farm in Steuben County. With horse shows and races canceled, the pandemic “basically shut the industry down.”

In addition, roughly 10 percent or less of New York farmers are Amish or Mennonite and do not accept any forms of government assistance, said Judson Reid, a specialist at Cornell Cooperative Extension who has studied those communities’ farming practices for decades.

Other New York farmers told the Times Union they also prefer not to participate in USDA programs.

“I just don’t need the government in my back pocket,” said Don Bikowicz, who owns a 25-acre vegetable farm in Glenville. He said his biggest concern was the paperwork that would be required. “It is just not worth it to me.”

U.S. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, who serves on the Senate Agriculture Committee, said she’ll fight for resources for New York farmers from the USDA.

“Many farms across New York state were financially strained before the pandemic, and they need robust federal support to recover from the economic crisis,” the Democrat said. “While the CFAP program was designed specifically to keep our farmers afloat, it is clear that inequities in distribution need to be investigated, and corrected, as the program continues.”

On March 24, USDA announced it would reopen the program for more applications and focus on getting the payments out to farmers who had been missed.

The agency said it would spend $2.5 million to improve outreach to farmers who had been overlooked. It also announced it would direct $6 billion to develop new programs or modify existing ones to offer further assistance to dairy farmers, specialty crops, beginning farmers and organic farmers, among other measures.

“Their recently announced plan to tailor outreach to smaller farms and better ensure independent operations can get the help they need is encouraging, but I will remain unsatisfied and continue to demand answers until the problem is fixed and our lifeline to America’s small farmers and specialty growers is established as Congress intended,” Tonko said.

The Environmental Working Group’s Schechinger put it more bluntly: “We’ll be watching.”

Kyle Ogilvie is a volunteer data consultant with the non-profit DataKind DC who supported this investigation through a partnership between DataKind and the National Press Foundation.