Aotearoa produces about 3 per cent of the world’s milk. Most of it goes overseas – so much, in fact, that dairy accounts for about 20 per cent of all exports.

There are several companies that buy raw milk and turn it into dairy products. One casts a shadow over the rest: Fonterra, a co-operative owned by about 10,000 farmers. Fonterra’s annual revenue is typically about $20 billion. It employs about 20,000 people worldwide. It enjoyed an after-tax profit of $659 million for the 2020 financial year.

It used to process about 96 per cent of all New Zealand’s milk. That number now stands at about 81 per cent, with the rise of companies such as Open Country Dairy, Synlait and Westland, who have chipped away at that overwhelming market share.

You probably know someone who works in the dairy industry. Or at the very least you probably read or watch stories about it. While this piece is not going to explain the entirety of a gargantuan (and complicated) business, it will hopefully make it a little more accessible.

The 101 of the business

There are other players in the milk game, but this will focus on Fonterra. Why? Well, its sheer size imparts a gravitational pull on the entire New Zealand economy.

Its operations quite rightly attract a lot of attention, and its unique and dominant market position also means it sets something called the farmgate milk price, the average price paid to farmers for a kilogram of milksolid (kgMS).

Stuff and other media report on the price a lot. We’ll explain how it’s derived, and exactly what milksolids are, a little later.

What you need to know right now is:

This price is really important.

It’s not set by invisible market forces like supply and demand. It’s an artificial price set by Fonterra (based on a complicated methodology) and something the milk suppliers must accept.

The price helps define Fonterra’s business model, which is actually fairly straightforward. It buys raw milk from dairy farmers. It turns that raw milk into dairy products. It sells those dairy products.

While it has different business units and subsidiaries, the company essentially sells:

Dairy commodities, like whole milk powder, on a global market platform it owns.

Ingredients to food manufacturers, or businesses like restaurants and cafes.

Dairy products to supermarkets for consumers to buy.

Fonterra announces the initial farmgate milk price when a dairy season starts around June every year. I use the word “initial” for a reason. The actual payments are delayed until Fonterra understands precisely what’s going on in the market in any given year. This means it can’t really lose.

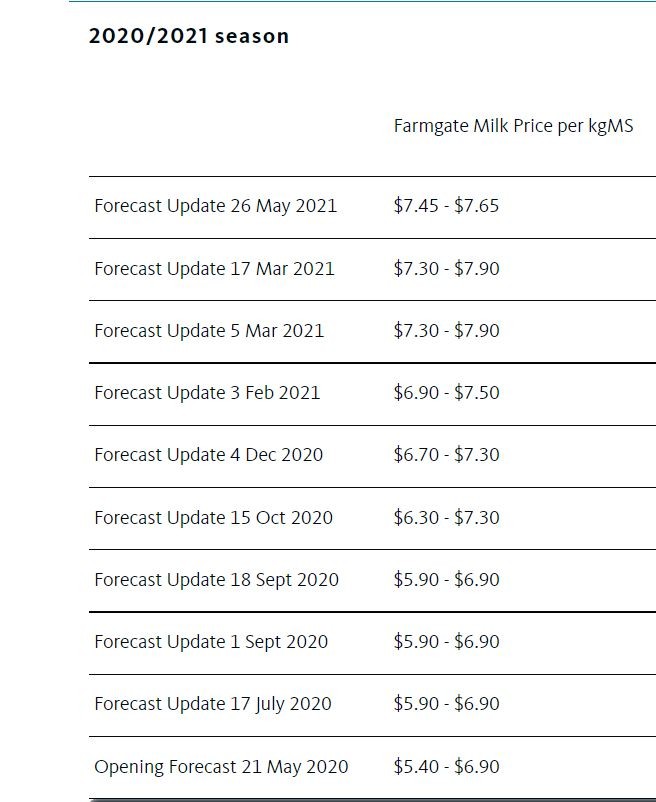

The evolution of the farmgate milk price in the 2020-2021 season.

This is an imaginary chain of events to illuminate what I mean.

The start of the dairy farming year. Fonterra says to all the farmers, “We’ll give you $7 for every kilogram of milksolids you supply”. The farmers accept it.

Suddenly the world inexplicably decides it’s no longer interested in milk.

Fonterra sheepishly goes back to its farmers and says, “Hey all. Going to have to round that price down a touch.”

A fantastical example, of course. But it illustrates the advantageous position Fonterra is in.

Those poor farmers!

Not really. The 10,000 farmers that supply Fonterra with raw milk also own the company and take on the associated risk of doing business.

Imagine the market goes the other way and the world decides to drink milk, and eat yoghurt and cheese morning, noon and night. The farmers will come out OK.

The farmers own Fonterra shares based on the volume of milk they produce in a given dairy season. Right now, a farmer has to hold one share for every kilogram of milksolids supplied.

Fonterra also pays out profits to farmers. For example, in the 2019-20 financial year it paid out 5 cents in dividend for every share held.

So let’s say there’s Carol the imaginary farmer. Let’s say the farmgate milk price is $8 per kgMS. Now let’s say Carol owns 100,000 shares and supplies 100,000 kilograms of milksolid.

Carol will be paid $800,000 for her milk solids and an extra $5000 in dividend (assuming a pay out of 5c for every share held).

There are proposals to change the obligation for farmers to own one share for every kilogram supplied. The plan is to make it cheaper and easier for farmers to buy into Fonterra – they’d only need to hold one share for every 4kg of milksolids supplied.

The reason? Fonterra is worried about the future of milk supply. There are more environmental restrictions, it says, that will lead to dairy farming becoming less attractive and straightforward. The proposed set-up would make it easier to get shareholders onboard to supply all that milk.

Let’s talk about the global dairy trade

I thought you’d never ask. Fonterra owns this thing called the global dairy trade, where twice a month people from all over the world gather to buy and sell dairy products.

Think of these auctions as a kind of Tinder for people who want to buy tens of thousands of metric tonnes of milk powder.

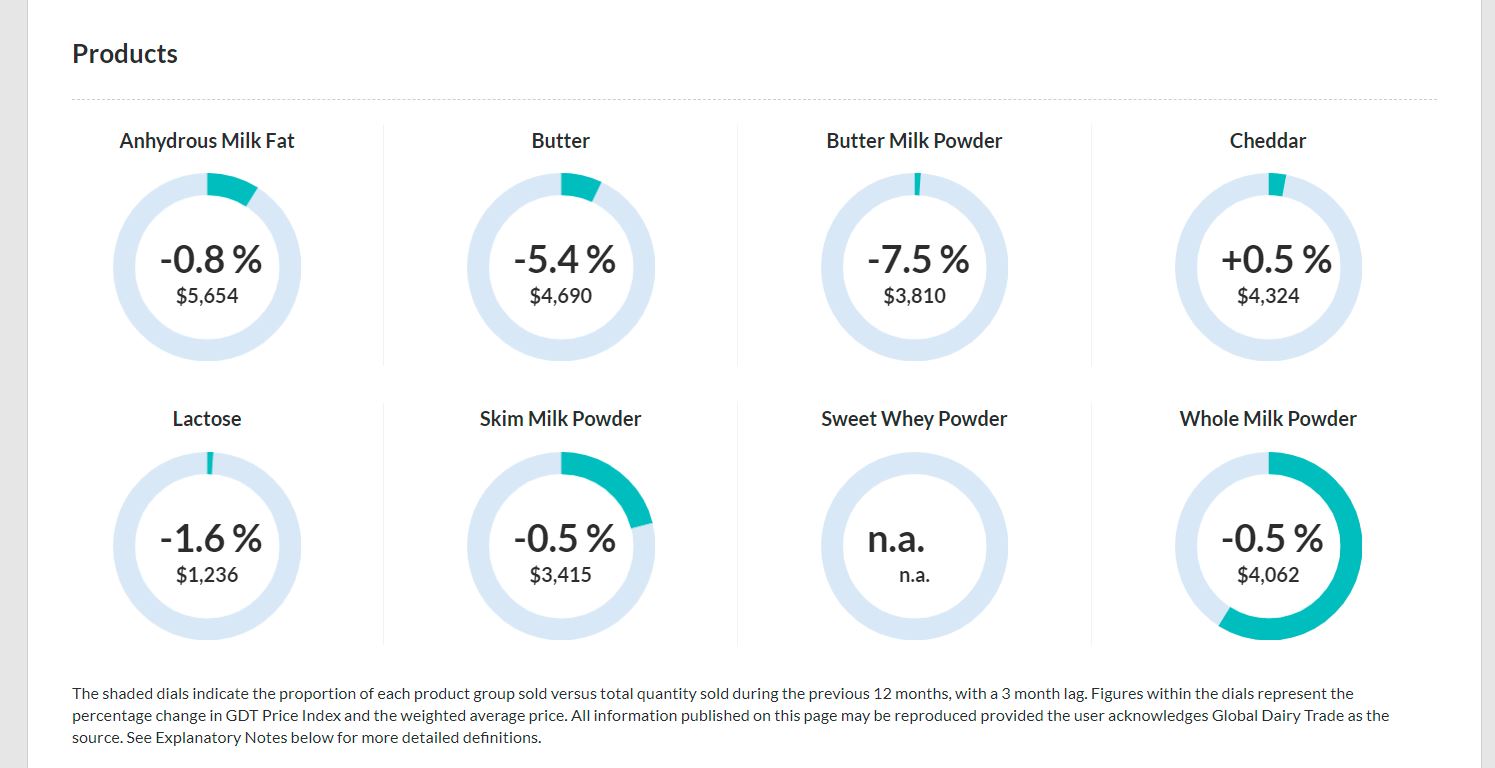

The products up for sale include whole milk powder (WMP) and skim milk powder (SMP), butter, anhydrous milk fat (AMF) and buttermilk powder (BMP).

The dairy commodities that are available.

These are called dairy commodities. When economists talk about commodities, they mean goods that are pretty much the same whoever produces them. Iron, for example, is a commodity. Smartphones are not.

The trade starts with the bidders outlining how much they want to buy based on a starting price, informed by previous auctions.

Say those buyers want 50,000 metric tonnes of whole milk powder. But there’s only 25,000 metric tonnes available.

The simple economic principles of supply and demand apply. If you want whole milk powder, you’re going to need to pay more to beat out the next guy.

So the price goes up. A few bidders drop out. The remaining bidders want 40,000 metric tonnes of whole milk powder at the new price. Demand is still outstripping supply, so the price creeps up again.

This continues for a few rounds until the sweet spot is reached – where the quantity bidders are willing to buy is the same as the sellers are willing to sell.

How do I keep track of this?

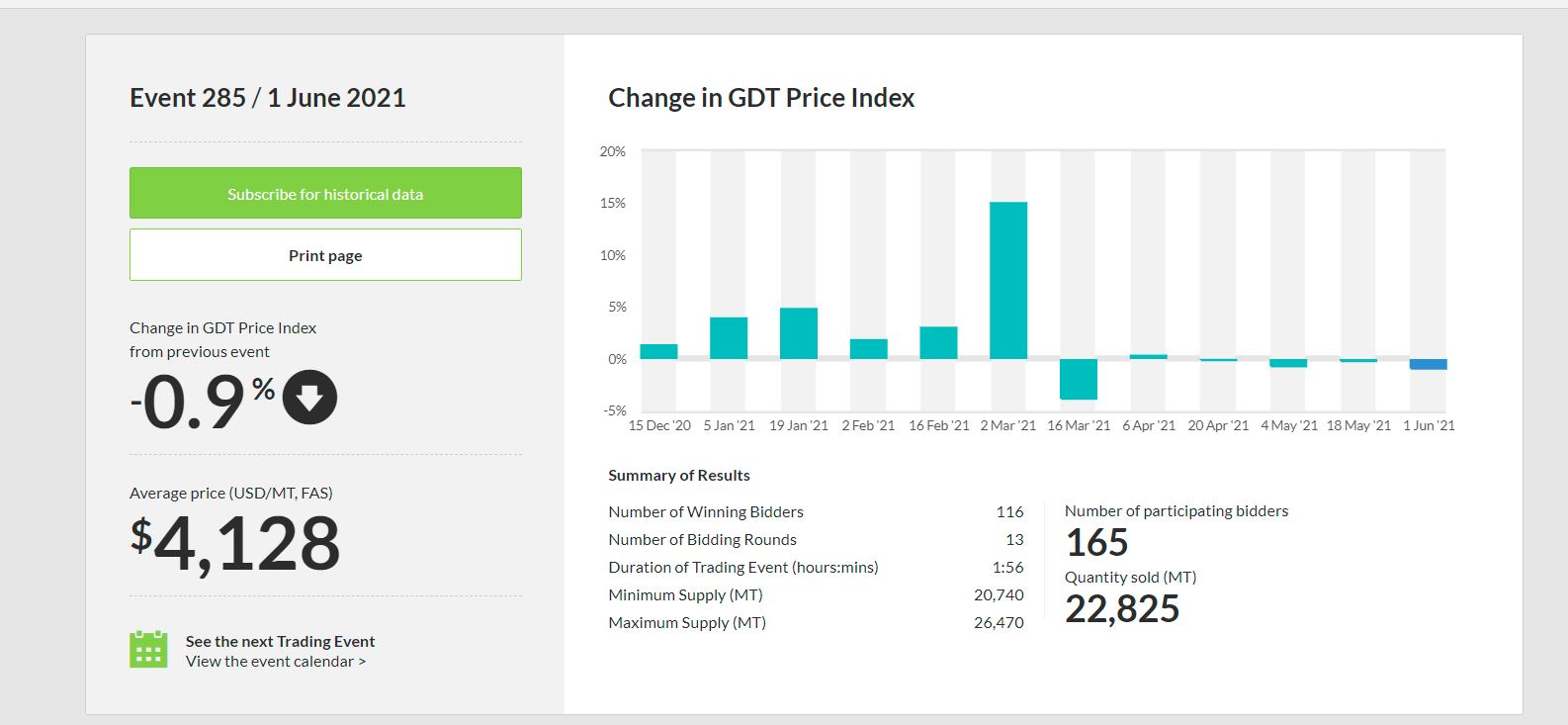

Go onto the global dairy trade website, and you’ll see what’s called a price index. This is essentially a simple percentage that illustrates what’s happened to the price of all those commodities between the trading events.

The global dairy trade website shows the index and the average.

Media, including Stuff, also report on this. In this story from May 5, for example, we said:

Dairy prices eased in the overnight global auction, as a lift in the price of milk powders failed to offset a decline in butter and milk fat prices.The global dairy trade price index slipped 0.7 per cent.

This price index was developed as a simple reference point to make the global dairy market understandable. Simply put, it’s totted up by working out the average percentage price change for each of the commodities mentioned above, factoring in the quantity of each sold.

As you can see above, the global dairy trade also publishes an average price. Right now, that’s $4128 USD/MT/FAS. Lots of acronyms there, eh? That’s US dollars per metric tonne of a commodity. FAS means Free Alongside. This is a shipping term. It means the seller must sort it out, so the goods are parked up next to the buyer’s waiting cargo ship.

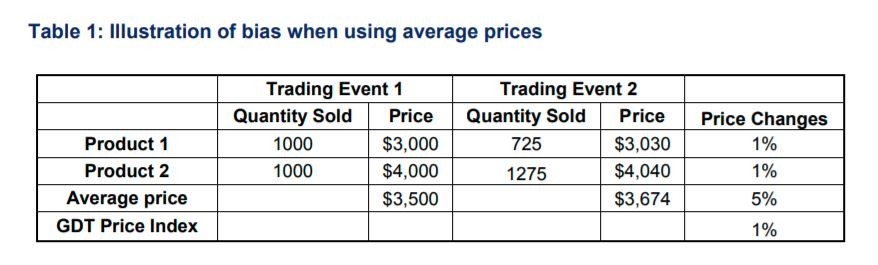

While the average price would appear to be useful, it can be misleading. Let me explain.

Say, there are two products. The price of both goes up by 1 per cent between two trading events. However, more of the expensive product has been sold and less of the cheaper product.

So even though the price of both went up by 1 per cent, the average price increase is 5 per cent. This is not ideal, which is why an index is necessary.

This example illustrates the need for an index.

Back to the farmgate milk price

If there were loads of Fonterra-style companies competing against each other, they’d all make bids for farmers’ raw milk. Eventually an equilibrium would be reached, and the farmers would make a call on whom they want to sell to.

New Zealand’s milk market is not normal. Sure, there are other dairy companies that process milk. But Fonterra’s sheer size has created abnormality.

Given this abnormality, Fonterra can’t rely on the market to set a fair price for farmers. It has to work it out itself.

In a nutshell, Fonterra calculates the money it will make from all the milk it plans to sell. It then deducts the costs associated with processing and selling all that milk – along with other costs of doing business – and what’s left goes to the farmers.

The price paid for the commodities at the global dairy trade events help Fonterra define its expected revenue.

After doing all those complicated calculations (there’s an entire manual dedicated to how this is done, by the way), this is the farmgate milk price.

The global dairy trade informs the farmgate milk price – and the farmgate milk price informs the global dairy trade events.

Doubling down on dairy

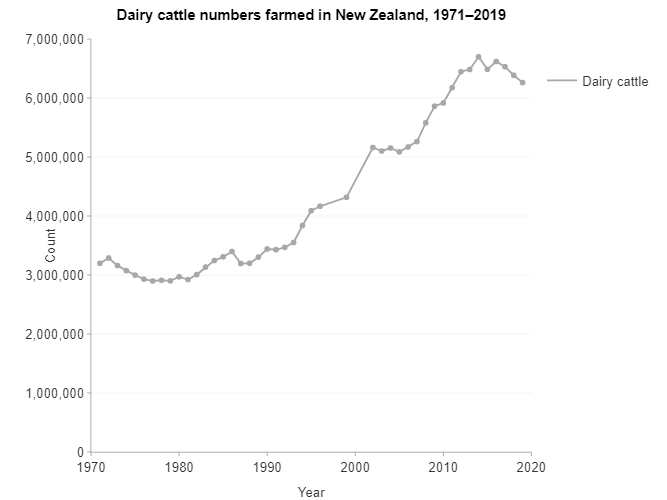

Dairy cow numbers have doubled since the 1970s but have begun falling again in recent years.

But you said Fonterra can change its mind?

I did. While Fonterra predicts the farmgate milk price in advance for a particular milking season (which begins on June 1, by the way), it doesn’t pay out in advance.

The farmgate price is essentially an estimate. There’s no guarantee. If, for whatever reason, there was an unexpected fall in demand for all those dairy commodities, Fonterra would not earn the revenues it expected. Therefore, it wouldn’t be able to pay the farmers what it didn’t earn.

Right now, Fonterra says the price it expects to pay for the milk in this particular dairy season sits somewhere between $7.25 and $8.75 per kgMS.

As time passes, Fonterra will learn more. And as it does, this rather broad price range will get narrower.

Let’s talk about milksolids

We know Fonterra pays farmers for kilograms of milksolids. Um, what are milksolids?

Take the average litre of milk. It’s made up of about 85 per cent water, and about 15 per cent solids. Those solids comprise protein, fat, lactose and various minerals.

Fonterra doesn’t actually pay for all of this stuff. It pays farmers only for the fat and protein supplied, which is about 8.5 per cent of the supplied milk.

That means that, when you see a farmgate milk price of $8 per kgMS, it’s not really $8 per kg of milksolids – it’s $8 per kg of fat and protein.

Confused yet? Oh, you will be. Fonterra also technically pays different prices for fat and protein. Both have different market values.

And, of course the amount of fat and protein in milk varies from farm to farm. Cows aren’t identical machines. Some farms might have a touch more protein, others a little more fat.

So when you read the farmgate payout will be $x per kgMS, that’s the average payout for the average farmer. It’s not the same for everyone.

To work out what it’s going to pay to an individual farmer, the milk is sampled as it goes into the tanker.

Milk itself is simple. The business of milk is not.

Clarification: The second to last paragraph of this story has been updated to better reflect how milk is sampled.