Every few months, there’s another story about Wisconsin’s declining dairy industry and the family farms that are going out of business. With the COVID-19 pandemic, that trend has continued even while other industries appear to be recovering.

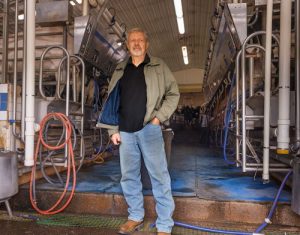

Joe Bragger doesn’t need to read about it; he sees it whenever he goes from one end of his dairy operation to the other. Along his driveway there’s an abandoned barn from before his time. As he approaches his farm, he passes the lot where three of his classmates lived on their family’s dairy farm. All that stands now is the abandoned house.

“That family lived entirely off of that farm, the kids went to school, they were part of the community. And eventually that became not a viable farm and they’re gone now,” Bragger, a farmer in Independence, said. “Now it’s buildings that are becoming dilapidated, no longer maintained, and it’s no longer an economic driver.”

As he gets closer to his own 300-head dairy operation, he worries that his land is heading towards the same end.

“What’s required now to be able to grow, to push out the numbers, is not sustainable in many of these areas,” Bragger said. “You just can’t build to get the cow numbers up high enough in a sensible way.”

In 2018, the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture reported that 638 dairy farms had closed. In 2019, that number went up to 818, 10% of the total number of dairy farms in the state at that time. The Wisconsin Examiner reported that in 2020, the industry was kept afloat by the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, which infused $564 million dollars into Wisconsin’s dairy farms. But as the rest of the economy recovers, dairy farms are returning to pre-COVID conditions with a glut of product flooding the market and resulting in low prices for producers.

Bragger is of the mindset that any help is appreciated, whether that’s bills recently passed in the Legislature regulating the labeling of alternative milks (almond or oat milk) or provisions in the state budget to increase exports.

The Wisconsin Farmers’ Union said the state budget as introduced by Gov. Tony Evers included many items they supported, such as expanding BadgerCare (which would expand access to mental health services), grants for new meat processors, and conservation programs. Those items were removed from the budget by Republicans on the Joint Finance Committee, who instead replaced them with a program to expand exports.

But at the end of the day, farmers like Bragger and Travis Klinkner of Genoa realize there’s not much that can be done to solve the issues farmers face at the state level.

“Those are all Band-Aids to a real, major problem, which is that the farmer isn’t receiving an equitable, fair price,” Klinkner said.

More than enough

The heart of the problem with the dairy industry is simple: supply and demand. Dairy farmers are producing more milk and dairy products than the market consumes, which drives down the price they can receive for it.

Regulating milk production to ensure a better price for farmers cannot be done effectively at the state level. Michelle Miller, associate director at UW-Madison’s Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, has been working with dairy organizations and representatives to develop a model for managing supply. She said they’re close to developing an application where farmers can input their operations’ data and see how different models of supply management would affect them.

But any supply management system would need to get past the market-centric mindset in Congress. One model almost made it into the 2014 Farm Bill, but it was killed by then-House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio), who called it “Soviet-style agriculture.”

Until a management system is up and running, farmers’ options are to reduce the cost of production and continue to make more milk, which Bragger pointed out is what’s causing the pricing issues in the first place.

“What do farmers do when the price is high? Milk more cows. What do they do when the price is low? Milk more cows. Unfortunately, that’s the way the system is set up. The answer has always been more milk to drive profitability,” Bragger said. “The other little things are nice, but they’re not going to turn around the difficulties that we’re having anytime quickly, because they’re the things we’ve done all along.”

Same old band-aids

If the US market is saturated, then expanding Wisconsin dairy’s export market seems like it would help. That is what Republicans on the Joint Finance Committee decided to prioritize during the budget process for the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection.

The problem is, according to Miller, the cost of production in the US is so much higher than it is in other countries that are also exporting their milk products.

“If a farmer can’t produce milk for $14 a hundredweight or less, they’re not going to be able to compete on the world market,” Miller said.

Klinkner said that putting US dairy on the international market without buyers lined up creates another oversupply problem. Wisconsin resolves that by turning that milk into powdered milk products, but those sell at very low prices on the international market.

“So exports get rid of excess milk, but they don’t always translate into higher farmgate prices,” Klinkner said. “It’d be like me saying, ‘I’ve got two extra cows but nobody wanted to buy him. So I had to sell them at a loss. But hey, I got rid of them.’”

“You aren’t throwing it away, but it’s not anything that’s gonna really help our farm economy,” Miller said. “Politically, everyone likes the sound of it. ‘We’ll just export it and that’ll help.’ And that’s been the mantra that’s been used for a long time, but it’s clear that it hasn’t worked.”

Another policy idea that’s gained traction and even was passed by the Legislature last week, is regulating the labelling of alternative milks, such as oat, almond or soy milks. Bragger said he likes the idea because he likes “clarity.” Klinkner is on the same page.

“A lot of these soy products and almond products are claiming that they’re milk when they’re juices from a plant,” Klinkner said. “They’re not milk—milk comes from mammals—so that would create better marketing.”

But Miller called the move a “red herring.” At most, it could impact cooler space at the grocery store, but there’s no guarantee that that would change once alternative milks are relabeled.

“The reason why there are those options on the shelf is because people are interested in buying those things. Even if they didn’t have oat milk, they might not buy regular milk because they can’t digest it, they don’t like the way it tastes, they’re concerned about additives, who knows what the reasons are,” Miller said. “Dairy farmers are being thrown that bone, chew on that for a while, get all worked up … and then even if it changes, it’s not going to make any difference.”

The food dairy and meat labelling bills passed the Assembly and Senate. Evers as of Friday has not stated what he plans to do with them.

As for mental health and suicide prevention services for farmers, Klinkner pointed out they wouldn’t be so necessary if the federal government would address the heart of the issue.

“It’s good that we’re focusing on mental health for farmers,” Klinkner said. “But the reason they’re having mental health issues and feel suicidal is because of the stress of doing what they enjoy doing and not being able to make a living doing it.”

The biggest thing Bragger said state officials can do is to use their influence to get Wisconsin’s federal representatives and senators on board with the changes that need to be made.

“If we work together with a common voice to push those ideas that will help our farmers out here, we can accomplish that,” Bragger said. “That’s what needs to be done.”