The Wisconsin peninsula that separates the waters of Green Bay from the rest of Lake Michigan is about 20 miles wide at its base. The village of Luxemburg and Salentine Homestead Dairy are nestled into the rolling Kewaunee County hills halfway between the two shores. Although only a short drive from the bustling tourist destination of Door County, this is very clearly farm country.

Wisconsin’s “America’s Dairyland” slogan is nowhere more fitting than in Kewaunee County, where there are 80.2 dairy cows per square mile, the most in the state. It is home to 100 dairy farms milking 55,000 cows, according to the county’s Extension. That’s about 35,000 more dairy cows than people.

Salentine Homestead Dairy is home to 300 of those dairy cows. The dairy got its start in 1920 when Ben and Marie Salentine purchased the original 80-acre farm.

The second generation, Nick and Agnes Salentine, became owners in 1946. Jim and Mary Salentine took the reins in 1975. Son Josh had been working with his parents for years, but he and his wife, Jenny, formed a partnership with Jim and Mary in 2014, creating Salentine Homestead Dairy. The next generation — Megan, Caleb, and Molly — also help on the farm, along with two nephews.

Celebrating a Century (Plus Three)

Father’s Day 2023 was one of those dreamy Wisconsin summer days, the sun shining as temperatures started in the 60s and reached nearly 80°F by noon. The Salentine family stepped outside to celebrate Mass under a tent in their backyard and enjoy breakfast with 5,700 of their closest friends.

Each year, Kewaunee County Dairy Promotion selects a different family to host Breakfast on the Farm, an event that promotes June as Dairy Month. This year, the Salentines were chosen. They were actually scheduled to host in 2020, the year they received Centennial Farm status, but the event was canceled that year due to COVID-19.

A host of volunteers helped make the day a success. Dairy was the star of the meal, of course, with fresh cheese, omelets, yogurt, fried cheese curds, pizza, strawberry sundaes, milk, and more treats. Tours showcased the herd and facilities, and entertainment included live music, a tractor show, a petting zoo, and horse-drawn wagon rides.

Jim, Josh, Jenny, and the children greeted guests and answered questions about their farm and the dairy industry, but one person was missing: Mary had passed away unexpectedly in the fall of 2022. “We find comfort knowing you have the best seat in the house and get to watch the joy on everyone’s faces as they experience a little bit of what farming is like,” the family said on the farm’s Facebook page.

Jim and Mary hosted the breakfast once before, in 1992. There were 1,700 people in attendance that year.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/danhagenow_salentines_preview-208b7a934d584d0eaa35aa31f785baca.jpg)

Changing With the Times

Dairy farming is not for the faint of heart. The hours are unforgiving, and rising operation costs, lower milk prices, and consolidation have hit the industry hard. Small, family-owned dairies are finding it difficult to stay afloat. Wisconsin lost one-third of its dairy herds between 2014 and 2022.

While Jim and Josh work to stay true to their ancestors’ vision for the family farm, they’ve also expanded and made updates.

When Jim and Mary first took ownership, they expanded from 45 cows to 80.

“I kind of envy my dad’s generation a little bit because they were able to make it on 75 cows and some corn,” Josh says. “Now it’s all about risk management. You’re insuring your revenue and managing your inputs.”

Jim says, “Remember, though, in the early ’80s, we were paying 21% interest on our loans. That was tight.”

In 2000, the Salentines transitioned from a stanchion to a double-eight milking parlor and added a free-stall barn, allowing them to double their herd to 160 head.

“It’s hard to find help for stanchion barns,” Josh says, “but you can put someone in a parlor pretty easily. Feeding, milking, manure — everything is more efficient.”

“We used to bale all of our hay,” Jim says. “Finally we put up Harvestores for haylage and high-moisture corn. That really helped.” Now they store feed on an asphalt feed pad.

To maximize their space and resources, the Salentines in 2015 decided to have their calves raised off-site at a nearby farm. Heifers are sent to a ranch in southwest Kansas where they are raised, inseminated, and individually tracked.

“The heifers go out at 5 months of age, then they come back two months before they calve,” Josh says. “That gives them time to get reacclimated with the weather before they calve, and it helps us with our facilities and our labor.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SalentineCows-27b660d374f6402baa4b4e4c471fee52.jpg)

Current Snapshot

Today, between owned and rented ground, the Salentines grow 560 acres of corn, soybeans, alfalfa, and wheat, using contour strip cropping where beneficial.

Their 300 cows are milked twice daily, each averaging 80 pounds of milk per day. Cow comfort is the top priority.

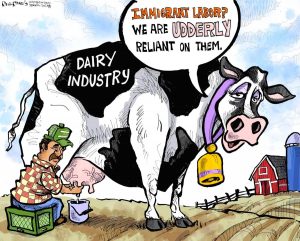

The farm has nine part-time employees and often hires workers from Honduras. Immigration laws and housing have affected the farm’s workforce, but Josh says, “The group we have here is phenomenal.”

Jenny does chores and payroll for the dairy, but works off the farm, which is important for health insurance and retirement, Josh says. He took over the books after his mom’s passing.

Having a team of experts, including an agronomist, accountant, estate planner, attorney, veterinarian, nutritionist, and marketer, has helped the family succeed. “Have a plan and know that it can change,” Josh says.

Looking to the Future

If any of his children want to join the family dairy, Josh says he’ll find a way.

“If I do add on to the barn, there will be spots so we can add robots later,” he says. “The technology has come so far, and every day the robots are out, that’s the worst they’ll ever be. They’ll just keep getting better.”

Meanwhile, Jim and Josh will continue to grow crops and milk cows on ground that has been in their family for a century. “I just like farming,” Jim says. “It’s a pretty good life.”