Stoicism has its place, but merely trudging along should not be our default, says Ben Anderson.

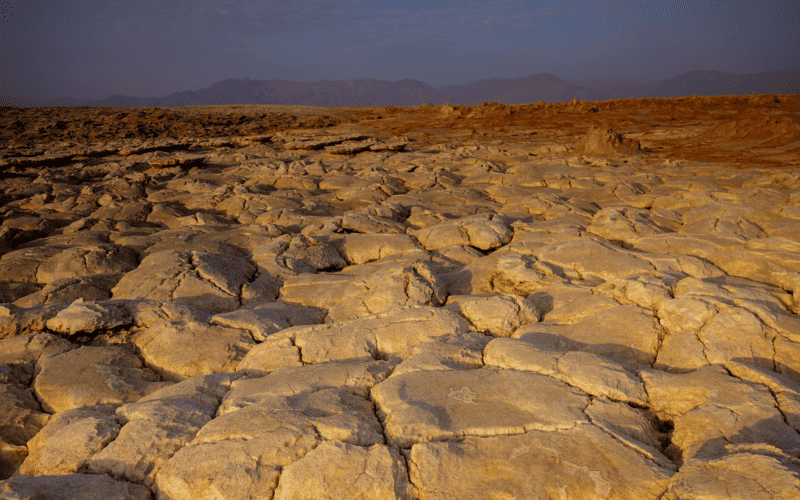

The Danakil Depression is the hottest place, on average, on Earth. Located in Ethiopia, it sits at the very juncture where the Horn of Africa is slowly tearing itself away from the mainland.

Supercharged by geothermal heat, the windswept volcanic rock floor of the depression easily reaches 55degC in its hottest months, making life there, for most things, impossible. When the wind rises, it feels like putting your head in the door of an oven on fan bake and simultaneously having handfuls of sharp volcanic sand thrown in your face. It’s brutal and was all too much for this boy.

Fortunately, the Afar people are made of sterner stuff than me. They have adapted to life in the Danakil and have even managed to make a living from it.

Within the Danakil is a place called Lake Afar, home to the salt mines that provide almost all of Ethiopia’s salt. The Afar salt miners cut slabs of salt from the evaporated lake crust, before carting it across and out of the depression by camel train over 80km to the nearest trading town. For their labours, the salt miners received around 5 US cents (about 8c) per slab of salt. Just enough to live on.

From the air-conditioned safety of my truck, I watched the Afar cameleers lead their strings of camels out of the haze and across the desert floor in a seemingly continuous train that stretched from one horizon to the other.

Both camel and cameleer seemed almost oblivious to the scorching heat and sand flying around them. As a young bloke with the usual youthful arrogance about my physical ability, I remember that humbling feeling when I recognised that the Afar measured their physical and mental resilience with a completely different yardstick than I did.

Southwest of the Danakil Depression and 14,359km away lies our own little slice of paradise. As this year draws to a close, it seems that we have had to face down a few extra challenges of our own.

There haven’t been too many 55degC days for sure, but we’ve had other demons. In February, Cyclone Gabrielle blew many farms in Hawke’s Bay to bits. High interest rates, low commodity prices and geopolitical turmoil have also contributed to an environment where many farmers on the east coast are now questioning their future in the sector. The juice is increasingly not enough to justify the squeeze.

Like the Afar people, New Zealand’s farmers like to pride themselves on their ability to withstand hardship. To be resilient and to roll with the punches. Stoicism forms not only an important part of our self-identify, it also underpins much of what we do on a daily basis. When times are tough, it is logical to just keep putting one foot after another.

But here the comparison ends.

The Afar people have for the most part no choice in where they live and what they do. They can see the opportunities and possibilities in the world around them, but they have no practical means of getting out of there. They have to keep on keeping on.

In comparison, we don’t. We have a world of opportunities available us. We are uniquely positioned to benefit from an increasingly global focus on sustainable food systems. We are almost embarrassingly well equipped to provide the high-quality food and fibre products that the richest in the world demand.

Our climate will be comparatively less affected by climate change than other countries. Our government is stable, our international reputation strong and our land productive. Most importantly, we have access to the research and capital required to take us being from raw undifferentiated commodity producers to producers of high-value food and fibre products that are sought after in our global markets.

To get there, farmers need to move beyond just being stoic and recognise that better is in fact possible. Our comparatively poor and fluctuating returns are not an inevitable reality. Nor is the environmental degradation that we still see in parts of our industry.

We now have a change of government, and it will be tempting for us farmers to see that as a vindication of the status quo. But I get the impression that this new government wants us to achieve our potential, both economically and environmentally. We need to take advantage of that and help the government to help us.

One part of this will involve being positive and embracing what we can do rather than commiserating over what we can’t. Another part will involve demanding the same from our industry leaders, who are appointed to serve our interests.

Stoicism has its place, but it should not be our default business model. We are lucky to have options. We should exercise them.