Last week, the Westbrooks sold their 84 dairy cows and some equipment to Allen County farmers Charlie Fisher and Ronnie Taylor, adding Westbrook Farm to a growing list of local and national dairy operations caught up in the contraction of the milk business.

“It’s not that we had to sell,” Millie Westbrook said. “But milk prices are not that good. If you sit down and look at the big picture, it takes so much work to make so little money.

“There’s good and bad to it, but I definitely think we made the right decision.”

It’s a decision that has become all too common for dairy farmers as declining demand for milk and other market forces have made it increasingly difficult to justify the early mornings and late nights required in dairy farming.

Farm Bureau statistics show the number of licensed dairy operations in the U.S. dropped from 70,375 in 2003 to 34,187 in 2019.

That downward spiral is maybe even more dramatic in Kentucky, where the number of dairy farms has fallen from 2,100 in 2000 to 435 today. In Warren County, the number of cow-milking operations has plummeted from 50 to 12 in the same period.

The rise of plant-based alternatives to cow’s milk, coupled with more-efficient dairy operations that squeeze out more milk per cow, has put downward pressure on prices.

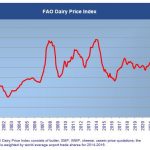

A graph of wholesale milk prices looks a bit like a roller coaster, but the trend is still southward. As high as $21.10 per 100 pounds less than two years ago, milk at the end of February was going for $17.10.

It’s the kind of trend that will keep you up at night, even if you don’t have a date with a milking machine.

“With prices like they are, it’s hard to make yourself get up at 2:30 in the morning to milk,” Millie Westbrook said. “It was pretty sad to sell the herd, but it’s a relief too.”

When a family has been in the dairy business for decades, sadness is the prevailing emotion.

“This will be the first time in my lifetime that we haven’t milked cows,” said Tim Westbrook, patriarch of Westbrook Farm. “When they (the cows) left, I kinda had tears in my eyes.”

But the elder Westbrook understands the market forces that led to the decision.

“The demand just isn’t there,” he said. “With milk prices where they are and the difficulty in finding help, it’s tough to make it.”

Bigger operations like Elkins Dairy in Smiths Grove, which has converted much of its operation to robotic milking, and those that innovate like Chaney’s Dairy in southern Warren County appear to be the survivors so far.

“It’s really sad,” said Dore Hunt, who oversees the 60-head Chaney’s dairy operation. “You devote so much time taking care of those animals and there’s no monetary reward.”

Hunt’s uncle Carl Chaney, whose farm has been in the family since 1942, has been a leader in the type of innovation necessary to make it in today’s milk business.

Chaney established Chaney’s Dairy Barn in 2003, selling ice cream and sandwiches and cashing in on the agritourism trend.

Chaney has since made the transition to robotic milking and to processing much of his own milk. Today, Chaney’s-branded milk is sold at some three dozen locations throughout southcentral Kentucky, and Chaney’s Dairy Barn on Nashville Road is selling ice cream made from its own milk and cream.

“We’re tickled to death with the sales of our milk and chocolate milk,” Chaney said. “Now we’re making strawberry milk.

“If it wasn’t for tourism and processing our own milk, I don’t know if we’d still be milking cows.”

Chaney can empathize with those who have left the dairy business, saying: “When you work with these animals every day, they become like family.”

Millie Westbrook acknowledges that attachment to the cows, but she said selling them to another dairy operation eased the pain.

“It’s easier seeing them go to another (dairy) farm,” she said. “That makes things better.”

Although there is now a void on the family farm, Millie Westbrook believes she and her husband can find ways to utilize the acreage devoted to the dairy herd.

“Landon has row crops (corn, wheat and soybeans primarily), and we have expanded our goat herd,” she said.

The Westbrooks have even dabbled in the emerging business of hemp farming, and they have started renting out a barn for parties and other events.

“There are a lot of other areas we could expand into,” Millie Westbrook said. “We have other options, and we’ll have more family time now.”