The dairy giant’s problems are deep seated, and the farmers who own it are partly to blame because they demand too high a price for their milk and starve Fonterra of the capital it needs.

STUFF

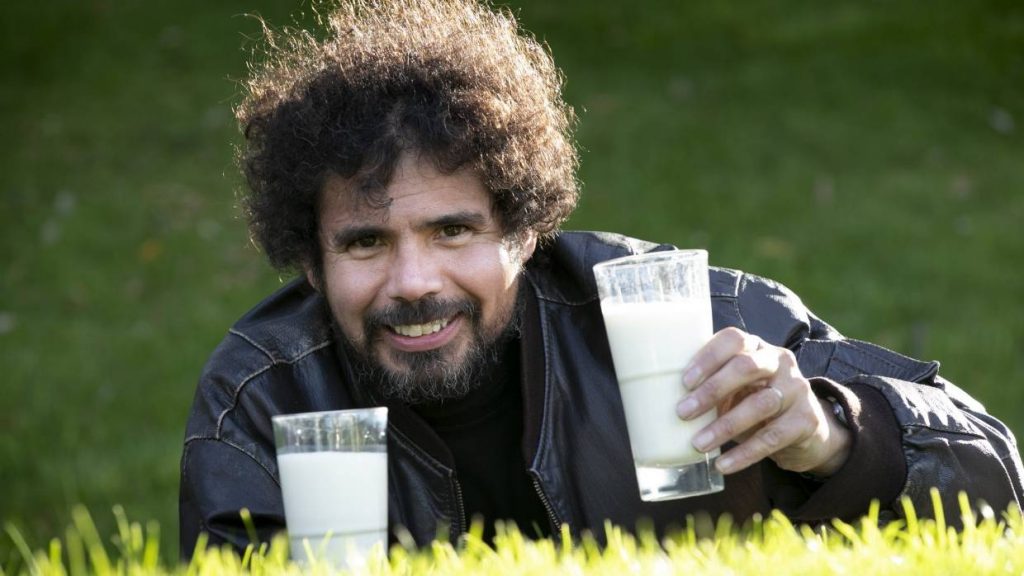

Economist Peter Fraser draws a ruler over Fonterra’s performance.

This week Fraser employed fire-and-brimstone rhetoric in a Victoria University presentation entitled Apocalypse Cow: why Fonterra has failed.

The self-described “guerrilla economist” has left a sour taste in the mouth of Fonterra management, who claim he has a conflict of interest because he has advised Agriculture Minister Damien O’Connor on changes to the dairy industry.

At the same time he is a consultant to a rival processor over the Dairy Industry Restructuring Act, which will be amended later this year. The act created Fonterra.

Fraser, who can often be found on Wellington streets in the early hours working at his specialist water blasting business, says it is no secret he is advising one of the independent dairy companies regarding the DIRA review.

“New Zealand’s a small place, all the experts on DIRA know each other and whenever there’s a DIRA review, it’s the same group of people who turn up.”

As far as being part of a recent “clandestine” meeting with O’Connor – described as such by a rural media publication – Fraser said he had never lobbied to meet with the minister but had received an invitation that he was happy to accept.

Last month O’Connor released the Government’s proposals to amend DIRA for the first time in 17 years, which were met with a mixed response.

In a bow to public concern about “dirty dairying”, the new law will allow Fonterra to refuse milk supply from farmers in circumstances where milk is not compliant or unlikely to comply with Fonterra’s terms and standards of supply or is supplied from newly converted dairy farms.

Fonterra’s terms of supply will include environmental, animal welfare, climate change and other sustainability standards.

But whether a revamp of the act will address the fundamental issues that Fraser raises is uncertain.

He says when the Government changed the law in 2001 to create Fonterra, it was to allow them do great things for the country and farmers, but instead little wealth has been created in the co-op.

At bottom the problem is that Fonterra pays farmers too much for their milk. The “retentions” – what is left over to run the co-op after farmers are paid – have not been enough to put it on a sound financial footing.

At the same time its share price has fallen by 40 per cent since 2012; in the last year, its total value has dropped from $8.2 billion to $6.25b. On the plus side, it has paid out $2.5b in dividends to farmers and unit holders since 2013.

But what of the $10 billion Fonterra returned to its farmer shareholders last year through the milk price and which has a direct impact on the rural economy? Farmers are estimated to spend about 46c of every dollar in their local community, and create jobs on farms and in factories.

Fraser argues even without the creation of Fonterra, there would have been a relatively thriving dairy industry. Most of the value Fonterra has created has gone into soaring land values.

“Fonterra is a private tennis club for the self-enrichment of its members. If you overpay for milk, the capital appreciation does not go into the share price but into farmers’ land.”

For years the mantra has been to add value to the milk Fonterra collects. Strenuous efforts have been made to do just that, so from a low base in 2001, 45 per cent of milk is now used for value add products.

Fraser is scathing in his assessment of the efforts.

“The foodservice business uses 45 per cent of milk and supplies 33 per cent of revenue. It’s not earning anything, they are wasting their time. What is foodservice? It’s getting a 25kg block of cheese, grating it and putting it in a bag for Pizza Hut. It’s a value added product but it’s not that flash. They would be better off putting it into milk powder.”

Analyst TDB Advisory backs this view of where Fonterra should focus its efforts. It says the return on commodities is surprisingly good, and suggests it should look at returning to shareholders a large amount of the $5b capital invested in its consumer and foodservice, China farms and international milk pools.

Fraser has little time for the complaint by Fonterra that it is hamstrung because under DIRA it has to collect most farmers’ milk. Rather, he says, “the milk has turned up because Fonterra wanted it”.

He points to the goal set by former chief executive Theo Spierings in 2016, to add a further billion kg of milksolids by 2026.

“Given it took 100 years to get to 1 billion, to get an extra billion in 10 years would be going really well.”

To start to turn the co-op around, Fraser would immediately remove 50c off the promised payment to farmers for 2019-20, restore the dividend to 30c, turn over the setting of the base milk price to an independent body, and ensure milk goes to the highest value processors.

He is not happy with the Government’s DIRA moves, which he says are a minor tweaking of the milk price setting regime and a weakening of the pro-competition measures.

He warns the proposed sale of Westland Milk Products to an offshore buyer is just a “dress rehearsal” for a potential sale one day of Fonterra to a foreign buyer.

Fonterra managing director co-operative affairs Mike Cronin responded in a statement:

“Our focus right now is on the future of our co-op. We’re well down the path of a strategy review which will enable us to deliver on our potential and meet people’s expectations. We know where we want to go, but how we get there will take time. We will play to our strengths – our New Zealand provenance, our pasture-based farming model and our dairy know-how.”