“That first month, really late March and into April was a time of complete upheaval in the markets,” said John Umhoefer, executive director of the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association.

Foodservice sales dropped off right away, and cheese processors were getting phone calls from distributors saying they weren’t taking any product, he said during the latest “DairyLivestream” webinar.

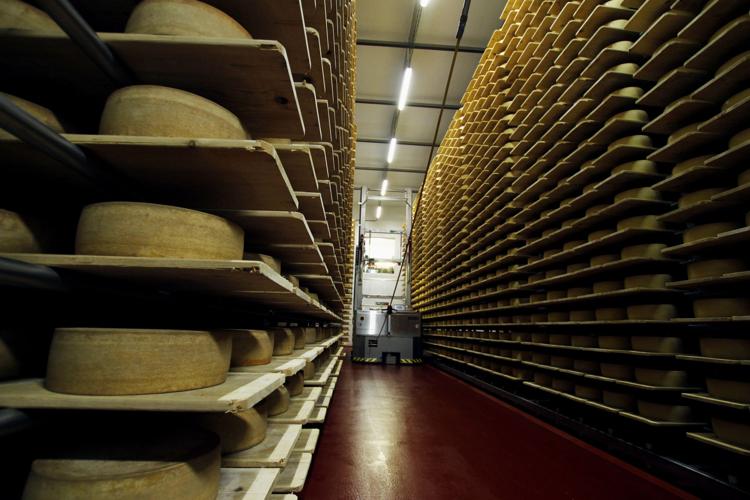

“Product backed up immediately last spring in the dairy industry. And so the first learning people had was what are we going to do with product that wasn’t meant to be held, and what are we going to do with this milk?” he said.

Processors pivoted and did things they hadn’t done before such as freezing mozzarella in bulk and shifting to products that could be cured instead of held as fresh cheeses, he said.

“They switched their make procedures. They switched their product mix. And they looked for new markets,” he said.

Some cheese makers found new markets in retail and the frozen pizza industry.

“So that ability to pivot in the marketplace was another early finding. And what struck me as I look back on last year is how quickly these things happened,” he said.

Some cheese makers switched from one cheese to another just days after states and restaurants started shutting down, he said.

The cheese distribution market was also in chaos. Contracts went from year-long and six months to monthly, then biweekly and then weekly, he said.

That shift is unprecedented, and it’s continuing, he said. There’s a tighter pipeline between milk coming in and product going out, and any disruption is magnified.

“Just the slightest hiccup at a good-sized cheese plant these days can cause a ripple effect across the entire milk shed,” he said.

Bryan Weller, director of procurement and sourcing for Agri-Mark, described the last year as a “problem whack-a-mole.”

The foodservice shutdown halted demand for the cooperative’s cultured products such as sour cream, which has no shelf life and can’t be frozen or aged.

“Luckily we’ve got a balance between foodservice and retail, but there were certain lines we had to shutter,” he said.

There just wasn’t demand for products such as 10-pound loaves of cheese. In addition, the pandemic brought a forecast roller coaster, he said.

After the holidays, February and March are kind of tumbleweed months for 8 ounce bars of cheese. But the pandemic brought a second Christmas demand, he said.

The cooperative sold a lot of those bars, but it certainly caused stress, he said. It had already incurred a lot of overhead with foodservice sizes and was suddenly maximizing lines that don’t put out the normal tonnage, he said.

And the issues haven’t stopped, he said.

“We’re probably under as much if not more stress than we were at the beginning of the pandemic,” he said.

There is still a labor shortage and employee distancing restrictions. And all the materials needed to keep facilities running, such as corrugated, plastic, lumber and steal, are in tight supply, he said.

“We’re all, I’d say, battle-hardened at this point. It continues to be a stressful environment for all facets of the industry,” he said.