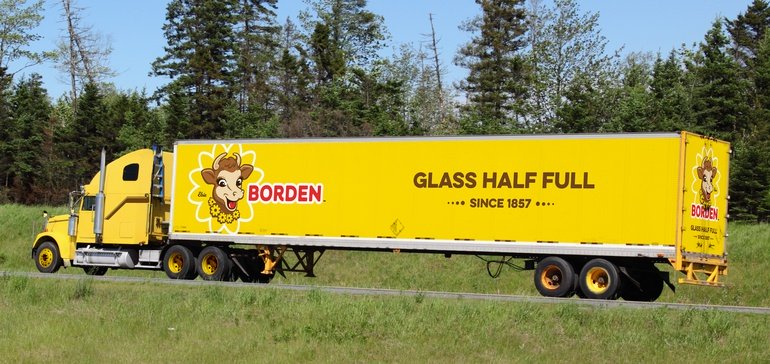

Weighed down by debt, Borden Dairy filed for bankruptcy in January.

The 163-year-old company planned to use the Chapter 11 filing to reorganize its business after some financial missteps left them with $250 million in secured debt, but it didn’t anticipate the coronavirus pandemic.

“Running a business is tough enough. Running a business in bankruptcy is tougher and then throwing a pandemic on top of that, even tougher,” CEO of Borden Tony Sarsam told Food Dive.

Both Borden and milk giant Dean Foods filed for bankruptcy just two months apart. Already struggling with shifting consumer demand, the milk producers took another hit as coronavirus shuttered foodservice operations, a major source of business for them.

Despite the hurdles it faces, Borden is working to get back on track. The company secured a major government contract to supply 700 million servings of fluid milk to nonprofits amid the pandemic, and just five months after filing for bankruptcy, the company is now finishing up that process in the expected timeline.

Two weeks ago, Capitol Peak Partners and KKR & Co. formed a joint venture and won a bankruptcy auction for Borden. Although union objections put the deal in jeopardy, the court approved the $340 million sale on Friday.

“We are exiting Chapter 11 as a thriving company that is meeting and exceeding its performance forecasts, making our outlook very promising,” Sarsam said in a statement after the sale was approved.

Capitol Peak is led by Gregg Engles, a former chairman and chief executive of Dean Foods, while KKR previously owned Borden and was already a lender. Capitol Peak will assume majority ownership of the new company, and KKR will be a minority investor. Sarsam, who led the company for two years, will step down as CEO of the company in July and Engles will take over with a new senior leadership team.

“My mission when I came here changed once we began understanding the realities of the debt problem that was weighing on the company,” Sarsam told Food Dive.

Borden will remain fully intact, including all branches and plants, and the reorganized business will continue to employ all its workers. The company’s 12 plants in the U.S. produce about 500 million gallons of milk annually.

“My top priority these last six-plus months has been to get the best outcome for all 3,300 employees at Borden, and this outcome with Capitol Peak is the best outcome,” Sarsam said. “For me and for perhaps a few others, we’re going to move in a different direction, but that was still our mission, to get the best outcome for Borden and we’ve done that.”

But even though it is reducing its debt load with familiar faces taking over, analysts say Borden will likely continue to be plagued by the issues hurting the whole dairy industry.

Filing for Chapter 11

Companies in the dairy space, like Borden, have grappled with mounting challenges in recent years from rising competition with alternatives, dropping milk consumption, innovative startups and discounted private label.

Borden once sold products in all 50 states, but as of last summer, it offered 35 products in the Midwest, South and Southeastern U.S. The milk processor cited a 46% decline in fluid milk consumption per capita from 1980 to 2018 in its filing.

“The company continues to be impacted by the rising cost of raw milk and market challenges facing the dairy industry,” Sarsam said in a statement when it filed for bankruptcy.

“Running a business is tough enough. Running a business in bankruptcy is tougher and then throwing a pandemic on top of that, even tougher.”

Tony Sarsam

CEO, Borden Dairy

But what pushed the company to file for Chapter 11? Its debt, Sarsam said. There were “some mistakes that were made during the acquisition from the summer of 2017 that unfortunately put more debt on the company than was reasonable for the size of the company,” he added.

That year, private equity firm ACON Investments took a major stake in Borden. He said that debt constrained the company’s ability to make basic investments in areas like its plants and equipment. Borden tried to reach a resolution with its lenders, but Sarsam said it was unsatisfactory so the “only choice was to go through a court-supervised process to restructure our debt overall.”

A future with familiar faces

Post-bankruptcy, KKR and Capitol Peak both provide ample experience in this challenging space.

KKR bought Borden for $2 billion in 1995 and took it private after about 68 years as a public company. However, KKR ended up selling off its brands and divisions during the next decade, although it stayed on as a lender. When Borden filed for bankruptcy, it had a $175 million loan held by firms including KKR. The private equity firm used what it was owed on the loan toward the Borden deal, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Eric Snyder, partner at law firm Wilk Auslander and chairman of the firm’s bankruptcy department, told Food Dive that KKR likely didn’t want to take over the company, but they didn’t have much of a choice because there aren’t a lot of buyers interested in milk processing. Swapping the debt for the equity was really the only option. He said the issues plaguing the industry aren’t going anywhere.

“You wash the company through the bankruptcy. You get rid of your lenders, your general and secured creditors, and they’re able to take the company back,” Snyder said. “But the fundamentals are still there, milk consumption is down.”

While KKR was reportedly unhappy that Borden decided to file for Chapter 11 in January, the company has now paired up with Capitol Peak for a takeover.

$340M What Capitol Peak and KKR are paying for Borden in its 2020 bankruptcy sale

$2B What KKR paid for Borden in 1995

Engles, who ran Dean for about 18 years, founded Capitol Peak in 2017. “The Capitol Peak team is excited by this unique opportunity to work alongside KKR and build this iconic dairy company,” Engles said in a release.

Engles has his own checkered past with the industry, but does have experience taking over rival companies. Back in 2001, Suiza Foods acquired its rival Dean Foods and Engles, who was CEO of Suiza, took over the newly merged Dean.

The company was lucrative at first, with Engles being referred to as a “milkman to the nation,” but it hit road blocks, facing antitrust lawsuits and dropping milk sales. Forbes even listed him as one of its Worst Bosses for the Buck in 2011, averaging $20.4 million in compensation over six years while Dean’s stock dropped an average 11% per year.

At the end of his tenure there, Engles presided over Dean’s spinoff of WhiteWave Foods, which included plant-based brands like Silk, and took over as CEO of WhiteWave, leaving Dean in 2013. He then sold WhiteWave for $12.5 billion to Danone in 2017.

Now that Engles will be heading up one of Dean’s rivals, many will be watching to see if he returns to his reputation as the nation’s milkman or continues to face the same problems at Borden as he did running Dean.

Dean Foods takes a different path

Just two months before Borden filed for bankruptcy, Dean Foods filed for Chapter 11 in November.

Similarly struggling with mounting debt, changing consumer demands and management blunders, the largest dairy producer in the U.S. announced its filing and said at the same time that it was already in “advanced discussions” with Dairy Farmers of America for a potential sale.

The milk giant recently completed its bankruptcy sale, where it sold off its assets piece by piece. The majority of its assets went to Dairy Farmers of America for $433 million, despite antitrust concerns that the deal could create market consolidation. Although more than 100 objections were filed in court in just three days after the sale, the Department of Justice approved the deal.

“I think this is a real blind spot,” Sarsam said. “Candidly, I think the Department of Justice missed some things here. There’s a vertical integration as well as horizontal integration — that has the potential to be bad for consumers.”

An antitrust lawsuit was already filed against Dairy Farmers of America in North Carolina after the deal closed.

“The combination of the fact that Dairy Farmers of America has government protections on their pricing, has government protections on their ability to collude on pricing, and now own the largest processor, those three things to me say we should probably take a little harder look at whether that deal was viable or not,” Sarsam said.

Bondholders from Borden proposed merging the two dairy giants if the DFA sale were rejected, but by that time, the bankruptcy court had already approved the sale.

“Well it was a better deal for practically everybody. The only loser in that deal would have been DFA. Because in our case, we don’t have vertical integration, we just simply have a merger of two companies and that would have the opportunity to have synergies and best practices that allow us to be better together,” Sarsam said. “But at the end of the day the DFA thing was orchestrated early, and by the time we got to the place where we could actually contemplate that, it was water under the bridge.”

Sarsam said that Borden differs greatly from Dean because Borden was reporting positive numbers last year and prior to the pandemic, which shows that “with the right balance sheet we can actually make money in the current environment.”

Borden’s earnings before debt payments and taxes is positive. In 2018, Borden’s sales reached $1.2 billion with a loss of more than $14.6 million, The Washington Post reported. For January 2019 through December 2019, it had a net loss of $42.4 million.

“We’re in a much more stable situation than Dean Foods,” he said. “Dean Foods is not just a debt problem; they had significant operations problems. They were losing money in a more severe way. … We have to think about our situation differently and it’s a more positive story. We have a business that as a business unit can actually go on and prosper in ways Dean could not.”

Government contract helps amid the pandemic

When Borden filed for bankruptcy, Sarsam said the milk supplier would continue normal business operations as it reorganized.

But the coronavirus pandemic added additional challenges to an already struggling category. As restaurants and schools closed, milk demand in foodservice was down, which makes up about a third of Borden’s business.

Some of its jobs revolve around those closed businesses so they have tried to redeploy those workers as much as possible, but Sarsam said as of earlier this month 3% or 4% were still furloughed.

In May, however, the dairy company was awarded the USDA’s largest contract through its new Farmers to Families Food Box Program to supply 700 million servings of fresh fluid milk to nonprofits.

“It offers a better stability for our overall business because it is more volume in a time when our volume is down,” Sarsam said. “Our volume has been down about 20% during this pandemic and having more opportunity to run and produce and ship and all that, provides more stable work hours for our employees and … better stability for our farm partners.”

More than 2,700 dairy farmers went out of business in 2019 as milk consumption declined, Borden said in its filing. Due to the drop in foodservice demand during the pandemic, farmers have been forced to dump millions of gallons of milk.

Sarsam said Borden works with a lot of independent farmers and for most of them, the company is the single source for their milk, “so if our business is down, their business is down. That’s a tough situation. So this provides more certainty for them, and provides a better financial situation for their business.”

“Nothing is more gut wrenching than watching a farmer destroy his crop at the same time where somebody on the other end supply chain doesn’t have enough to eat. And so I think this one actually fits the best spirit of how the government can help in a bridge that actually gets the food from the farm to the families,” he said.

Rohan Jaura, industry analyst at IBISWorld, told Food Dive the “lucrative government contract” Borden won during the lockdown is about 10% of its annual production. The contract, coupled with KKR reentering the market, “could cause a massive reshape of Borden,” he said.

During the pandemic, Jaura said there could be a slight increase in interest from consumers who never purchase milk during normal times but are buying it during lockdowns. However, he said Borden and other companies are aware they can’t change the shift in consumer habits, which is why they are developing “in” dairy products, such as flavored and higher-protein milks.

“Innovation is key to surviving in this industry. Plants and companies that only produced fluid milk will not be viable,” Jaura said. “New ownership may be able to find a way to lower costs in certain regions and some plants will close.”

Mary Ledman, global dairy strategist at Rabobank, told Food Dive that although retail sales for dairy have increased during the pandemic, these companies “can’t rest on their laurels here with these increased sales. They’re really going to need to bring things to the category to keep consumers coming back.”

“If we return to our previous habits, this won’t be enough to keep people coming back to the dairy category,” she said.

Remaining optimistic despite challenges

Last year, Sarsam told Food Dive he was optimistic that there is room for growth in the dairy space. Before the bankruptcy sale was approved, Sarsam said he remained “every bit as optimistic about the fundamental thesis of how Borden can be successful.”

He said consumers have already invested in a sense of trust in its “spokes-cow” Elsie and in the Borden label, so it will be looking to provide new innovations and products in the future.

“I think that those opportunities are out there for us to grab. They were held up by the practical financial problems we had prior to and during the bankruptcy, but those opportunities are still available, and so I remain quite optimistic,” he said.

When it comes to innovation, Sarsam said that if all the company is doing is milk in a different container or slightly altering the milk fat percentage, then those are not real innovations and “consumers aren’t really clamoring for that.”

He pointed to Fairlife as an example of a different kind of a milk offering that represented something consumers wanted. Fairlife, a joint venture with Coca-Cola, produces ultra-filtered milk, a higher-protein and lower-lactose product that boosted sales 42% in the first quarter of 2019 compared with the previous year.

“Innovation is key to surviving in this industry. Plants and companies that only produced fluid milk will not be viable. New ownership may be able to find a way to lower costs in certain regions and some plants will close.”

Rohan Jaura

Industry analyst, IBISWorld

For decades, fluid milk consumption has declined as some consumers have turned to new innovations and plant-based options. Even though it is still a very small share of the overall market, non-dairy milk sales in the U.S. increased 61% from 2013 to 2017.

“It’s going to take some disruptors to wake up some of the folks who haven’t made those decisions to invest in the future. If you’re not investing in the category today, you’re going to have a major challenge to survive,” Paul Ziemnisky, EVP of global innovation partnerships at Dairy Management Inc., previously told Food Dive.

But bankruptcy lawyer Snyder said if Borden does invest more in innovation, that money will be coming out of pocket. He said milk processing is just like coal, it’s outdated, and milk consumption is down almost 50% in the last 20 to 30 years so it’s not going to get any better.

“It’s a total disaster; it’s as simple as that,” he said.

Even though the category is in decline, Sarsam said continuing to be the most service-oriented dairy while introducing innovations will distinguish the company.

“Our focus is providing great service, providing new ways to bring energy in the category,” he said before the sale was approved. “I think to a degree, if the entire industry does the same thing then the entire industry will have a brighter future.”