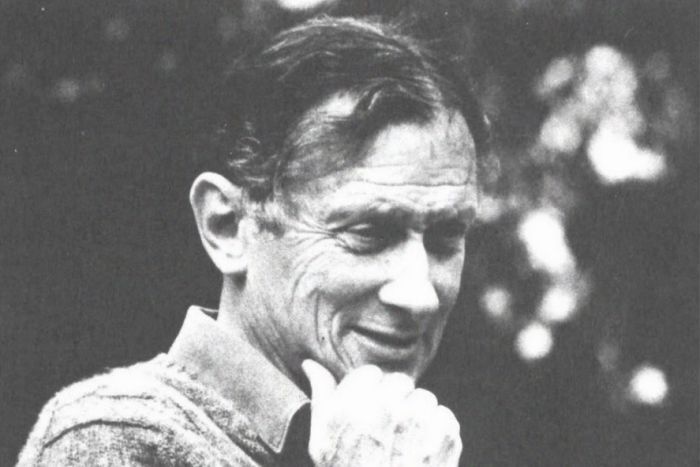

Not even the founding father of Australian biodynamics Alex Podolinsky knew the answer.

But 50 years later, farmers who follow this practice are paid top dollar for their dairy products, beef, rice and almonds.

This week, the world’s first international conference on biodynamics will be held in China, a fitting tribute to Mr Podolinsky, who died in June, just shy of his 94th birthday.

A controversial pioneer

Mr Podolinsky inspired an unlikely army of loyal troops, who every autumn across Australia scoop up fresh cow manure from their fields.

Then they squeeze the pungent green stuff into cow horns — many thousands of them — collected from abattoirs across the country.

The horns are carefully stacked and buried in earthen pits over winter, then they’re dug up in spring and emptied of a dark organic matter called humus.

This is the crux of biodynamic farming and central to Mr Podolinsky’s pioneering version of it.

He named it Demeter-certified biodynamic farming, after the Greek goddess of grain and fertility.

He then developed machines to convert the humus into soluble fertiliser to spray onto crops and soil, and discovered optimal times and conditions for when to do it.

This could mean the right phase of the Moon or the dark of night.

Sceptics dismissed his methods as akin to witchcraft and biodynamic farmers as deluded cult members.

Science is still largely at a loss to explain why cow horns create the rich humus while porcelain vessels and wooden boxes filled with manure do not.

Those who practice biodynamic farming care little about how it works.

They are more focussed on the fact it does, applying it to soil as well as fruit and vegetable crops across Australia.

Mr Podolinsky didn’t invent biodynamic farming; it was devised in the 1920s by German philosopher Rudolf Steiner to counter the rise of synthetic fertilisers.

Alexei de Podolinsky, born in Germany of noble Russian heritage, with an imagination fired by Dr Steiner’s principles, emigrated to Australia in 1949.

“He wanted to come to where there was light and light is an important part of a plant’s process,” Alex’s son Peter Podolinsky said.

“He was very conscious of nature and he saw things long before anybody else saw them.”

“In the 1960s, he was talking about carbon and things like that.”

On a dairy farm in Melbourne’s outskirts and later at Powelltown in the tall-timbered ranges further east, Mr Podolinsky closely observed his Jersey milking herd.

With the application of his cow-horn-created “preparations” known as 500, the farm’s fertility improved — as did the health and productivity of his herd.

The proof is in the price

By the mid-1960s, Mr Podolinsky was gathering followers and his methods were gaining momentum.

At Merrigum in Victoria’s fruit-growing region, Lynton Greenwood’s father was an early adopter of Mr Podolinsky’s approach.

The Greenwoods made and applied tonnes of compost and the orchard’s transformation was immediate.

The business has expanded in recent years and produces many varieties of pears and apples and a range of fruit juices.

All of it is biodynamic and all of it brings a premium price.

Lynton Greenwood has an easy answer to critics of biodynamic farming.

“The defence is we’re still here,” he said.

“[After] having started it many years ago when we were ostracised by our neighbours, most of our neighbours we’ve bought out since then.”

At Nathalia further north, three decades of biodynamic farming are paying solid dividends for dairy farmer Mark Peterson.

His herd size is half the district’s average but his biodynamic milk fetches three times the price of conventional milk.

The farm is almost self-sufficient, hardly needing to buy in fodder while elsewhere drought and poor milk prices bankrupt many.

“We were ridiculed 30 years ago when we started,” Mr Peterson said.

“Most of those people that passed comments have sold their farms, gone broke, moved on and we’re still here, so that’s a fairly telling story.”

Mr Podolinsky’s legacy is already sizeable.

Many believe the real worth of his sustainable farming model will be measured years from now.

He shunned notoriety but in a rare interview with the ABC 20 years ago said he was confident biodynamic farming would only get bigger.

And so it has. A few days ago, Vanya Cullen from a West Australian biodynamic winery was named Australian winemaker of the year.

In his later years, Mr Podolinsky reinvigorated biodynamic farming in Europe.

There is now growing interest in many Asian countries.