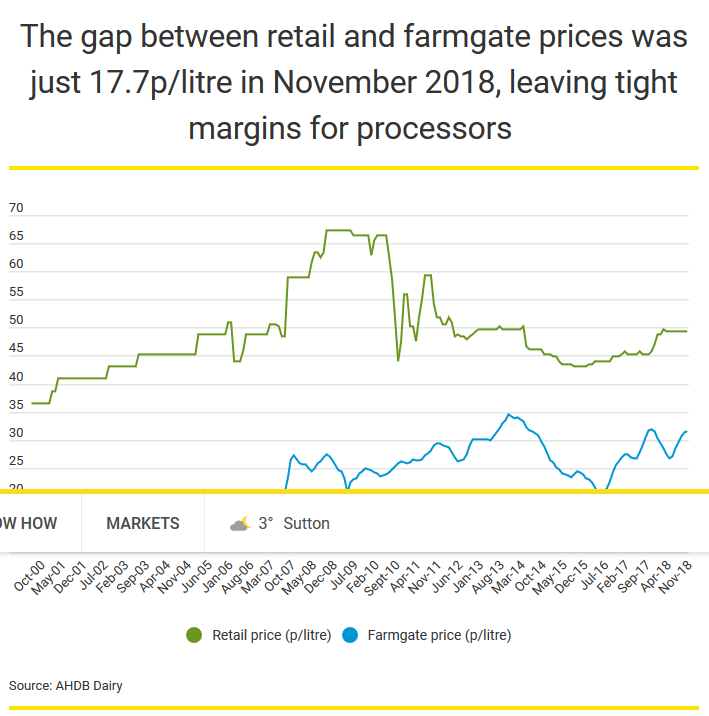

“We need to grow the size of the cake,” added Mr Walkland, who is an advocate of increasing milk retail prices to raise farmgate returns for dairy farmers.

Mr Walkland said that margins were believed to be only about 1% for milk processors on liquid milk, so growing producer milk cheques would require shoppers paying more at the till.

British consumers would be willing to pay more for milk, according to a 2016 YouGov survey.

The study, undertaken in conjunction with AHDB Consumer Insights, found that 80% of shoppers would be willing to spend more to provide producers with a fairer return, with 19% indicating they would happily pay more than 20p extra for four pints of milk.

Consumers have also shown their willingness to pay higher prices for milk, through Morrisons’ Milk for Farmers, which returns a 10p/litre premium to Morrisons’ Arla dairy farmer-suppliers.

Since October 2015, shoppers have purchased nearly 1bn litres of Milk for Farmers, returning an extra £12m to farmers’ pockets.

Milk in decline

The commoditisation of milk and its retail in “no frills” plastic containers in supermarkets is stifling excitement and innovation in dairy, according to journalist and Nuffield scholar, Tom Levitt.

“The market for milk is evolving, not disappearing, but milk has lost its monopoly,” says Mr Levitt, who undertook a two-year study of branded milk across seven countries.

“The problem is, held back by low margins in milk. the sector had been slow to adapt to the trends and desires of a new generation of consumers.”

He said that consumers were turned-off by red, blue and green plastic cartons of milk and the ugly metal trollies.

Some businesses had adapted to capitalise on the fact that 80% of UK consumers regularly bought milk, he says.

“People are willing to pay more for branded and innovative milk products.”

Mr Levitt pointed to the recent boom in popularity of kefir – a fermented dairy product half way between milk and yoghurt.

A 250ml bottle of branded kefir retails at a minimum of £1, a mark-up over standard liquid milk of more than 700% and already sells 16m bottles a year.

“[Kefir’s] biggest consumer base is slimming women, exactly the consumer that we are told is most likely to be avoiding dairy,” he added.

The only sustainable future for the industry is to turn milk into a more valuable and attractive product that consumers will be willing to spend more money on, warned Mr Levitt.

Target market

Generation Z – those aged between three and 23 – are the group that the industry needs to target, according to new Arla UK chief executive Ash Amirahmadi.

“This group aren’t necessarily against dairy, they are just more excited by plant-based at the moment.

“We just need to give them a reason to find dairy more exciting.”

Mr Amirahmadi said Arla’s future consumer strategy would be based around increasing the size of the pie through innovation of dairy products, urging other processors to follow Arla’s lead.

“We have to innovate products around milk. Milk is not just milk.”

“We have to modernise the category and appeal to young women. If we can do this, we will appeal to anyone out there.

“Lots of dairy companies need to produce products that consumers want to pay more money for.”

The Arla UK boss said that consumers need to be reminded that dairy is food in its own right, rather than an accompaniment to the likes of tea and cereal.

Branded milk in practice

Going it alone and launching an independent dairy brand has come with a whole series of challenges, but allowed Nemi milk to maintain full control of its brand direction, says Nemi director Andrew Henderson.

The brand, which retails at £1.49 for a two-litre bottle, is busy growing its UK liquid milk alongside developing its presence in global markets and already exports to the Middle East.

“We were offered a partnership with a major processor in the early days, but they wanted to own the brand.

“We didn’t want to end up like Innocent Smoothies selling themselves [to Coca-Cola] so we turned them down and have done things ourselves.”

Mr Henderson, a dairy nutritionist by trade, says this has allowed him to develop his selenium-enriched milk within his own ethics and, crucially, retained the power to pay his dairy farmer suppliers a fair return.

“We have never paid less than 30p/litre for any Nemi milk throughout the past two-and-a-half years,” he says.

Trying to enter a market dominated by the UK’s two largest processors has its challenges, adds Mr Henderson, citing the need for substantial start-up capital and access to existing transport logistics as his two biggest headaches.

“You need to know who your customers are and how you are going to get the milk to them. Logistics are crucial.”

Who is getting milk branding right?

Our Cow Molly

Sheffield-based dairy Our Cow Molly was launched in response to diminishing returns of the UK dairy processor market.

The brand prides itself on the freshness of its milk, with shorter supply chains meaning milk is on shelf in hours rather than days. The brand currently supplies several local coffee shops and in 2016 struck a deal to supply the Co-op in the town’s stores.

Fairlife milk

US dairy farmers Sue and Mike McCloskey created Fairlife to add value to their milk and highlight its nutritional and welfare benefits. In 2012, Fairlife went into a distribution partnership with Coca-Cola.

The product has 50% more protein, 30% more calcium and 50% less sugar than ordinary milk. The brand adds value by offering full traceability of its milk as well as interacting with consumers online and in person. Its farm has been branded as “the Disneyland” of agricultural tourism.

The brand retails at almost twice the price of regular milk at £2.20/litre.

C’est qui le patron? [Who is the boss?]

A French milk brand that has, since 2015, expanded into a number of other products, including pizza and apple juice, having sold more than 50m litres of milk.

The brand established a “fair price” for farmers by holding a consumer survey, where shoppers could choose how much they valued milk and therefore would be willing to pay farmers for it.

They chose €0.39/litre (35p/litre), which was 26% more than the average price. The brand, just 18 months old, is now in most major French supermarkets.