Gavin Newsom wins the California Recall Election. Follow our live results coverage.

Craig Gordon, the owner of several dairy farms near Los Angeles, is a lifelong Democrat. He supported Senator Bernie Sanders for president, he doesn’t like former President Donald J. Trump and he voted for Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2018.

But lately, he said, high taxes on milk, coronavirus shutdowns that have cut into his sales and state-imposed limitations on water for agriculture have made him so angry at Mr. Newsom that he has paid for seven billboards throughout the state — most of them in the Central Valley, which produces a quarter of the nation’s food — urging people to remove the governor in Tuesday’s recall election.

Mr. Gordon said he has spent about $44,000 for the billboards. “If I had to spend my last dime to get rid of this guy, I would,” he said. School closings during the pandemic have inflicted losses in milk sales of roughly $15,000 a day, he said. Between that financial blow and his taxes, he said, he’ll have to sell his cows and close the business by next year.

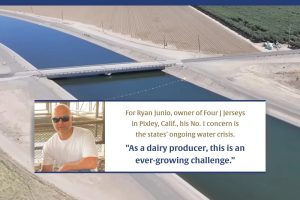

Farmers are a key constituency in California, where the $50 billion agricultural sector makes up about 3 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. During this year of exceptional drought, they are feeling the pinch of water restrictions, prompting many to support the recall of Mr. Newsom and choose a successor who they feel supports small businesses and will fight hard for their water needs.

In interviews in recent days, several farmers said Mr. Newsom hadn’t responded as urgently as they would like to their pleas for more water storage, such as dams, reservoirs or water banks, as a way of helping them through this drought and future ones.

“He’s not there for the state of California,” Mr. Gordon said of the Democratic governor. “We’re angry, and the people of the state want this guy gone.”

That anger spiked last month when the State Water Resources Control Board passed an emergency curtailment order for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta watershed, barring many farmers from using water from rivers and streams. With the drought, the Central Valley is experiencing the effects from years of pumping too much water from its aquifers.

“The stress that farmers and our farming community felt through Covid has just been exacerbated this year because of these extreme heat days and now drought,” said Karen Ross, secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture. “The pain that can be felt cannot be minimized. It’s very real.”

Mr. Newsom’s office said the governor supported farmers and ranchers, while also trying to promote water conservation and other measures to fight the effects of climate change. The state budget includes $5.1 billion to be spent over four years to mitigate the drought’s impact. This includes funding for emergency drought-relief projects that would secure and expand water supplies, and for drought contingency planning.

Mr. Newsom has also worked with the Legislature to push for more than $1 billion in spending on climate-smart agriculture, his office said. That includes the Healthy Soils Program, which provides grants to enable farmers to adopt soil management practices that sequester carbon. And Mr. Newsom has tried to spread the sacrifice; in July, he asked all Californians to voluntarily cut their water use by 15 percent. (About 80 percent of the water California uses goes toward agriculture.)

But in interviews, many farmers said the current water limits, combined with other state restrictions and taxes, have put a chokehold on their livelihoods.

Jerry Coelho, an owner of Terra Linda Farms in Riverdale, said that if the water crisis doesn’t ease next year, he’ll have to stop farming half of his 6,000 acres and use that water to help irrigate his more water-intensive crops, like pistachios, almonds and wine grapes.

He is aggravated that his water bills remain high while he gets only a small fraction of the water he says he is entitled to. And he is frustrated that there hasn’t been more immediate attention to creating new reservoirs, dams or water banks to harness water from the Sierra Nevada snowpack, a critical source. “There’s always an excuse as to why we can’t get water,” he said. “The worst thing of all is to do nothing.”

Climate activists and environmentalists have emphasized the importance of conserving water in a state that is growing increasingly drier with climate change. But Mr. Coelho said he feels that farmers have done everything they can to conserve.

He supports replacing Mr. Newsom with Larry Elder, a conservative radio host and the governor’s leading challenger, who has met with farmers on campaign stops, telling them in a Fresno appearance this month that if elected, he would immediately suspend the 1970 California Environmental Quality Act. That move, according to The Fresno Bee, would allow dams and reservoirs to be built more easily.

Farmers’ water needs have been a central cause in politics for decades, and a major issue in the state for a century, said Issac Hale, a postdoctoral scholar at the Blum Center on Poverty, Inequality and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“This is a complaint that has been in the Central Valley for years, and is a real source of tension with the agriculture industry and Democrats who are concerned about water conservation,” he said, adding that there’s a racial divide between farm owners and their workers, many of them Latino, who have traditionally voted Democratic.

About half of the voters who had returned ballots as of Friday are white, Mr. Hale said, which could benefit the recall effort. But ballot-return rates in the Central Valley were lower than in areas that usually support Democrats, he said.

Some farmers expressed sympathy for Mr. Newsom. “He’s the governor at a very difficult time, and I believe he’s done the best job that he’s been able to do,” said Don Cameron, the general manager of Terranova Ranch, about 30 miles southwest of Fresno, and a supporter of Mr. Newsom’s in the recall election. “There are a lot of farmers who don’t agree with that position, but it’s down political lines, unfortunately.”

For 30 years, Mr. Cameron has promoted his design for a water bank that collects floodwater by spreading it on farmland to seep underground, where it can restore aquifers and prevent flooding. It can hold twice as much water as a dam, he said. The state has adopted the idea as part of its larger plan to create a more dependable water supply.

State officials had to make grueling, but necessary, decisions about water use, he said. “They didn’t have the options. We know this is going to hurt. We’re always optimistic in farming, but we have a lot of things going against us right now, and without water, we can’t farm.”

Bryce Lundberg, who represents the agriculture business on the State Board of Food and Agriculture, said that while Governor Newsom had to prioritize the pandemic response, progress has still been made on water issues.

Mr. Lundberg, an owner of Lundberg Family Farms, which grows rice, said Mr. Newsom has prioritized plans for an environmentally friendly off-river reservoir in the Sacramento Valley called the Sites Reservoir. The reservoir would capture excess water from major storms and save it for drier periods.

“There are a lot of farmers under severe stress, and a lot of farmers who are going under business this year because they don’t have any water,” said Mr. Lundberg, who backs Mr. Newsom in the election. “It’s human nature to look for faults, but they’re not looking in the right place if they want to blame it on Governor Newsom.”

Some minority farmers are feeling particularly disappointed in the state, saying that their small acreage denies them the influence of larger farms that may lobby the state to make decisions, said Chanowk Yisrael, an owner of the Yisrael Urban Family Farm in Sacramento. Many farmers of color also rent their farmland from other farmers who may reduce the renters’ water supply rather than limit their own.

Mr. Yisrael said he hasn’t decided how he’ll vote, but he understands that Mr. Newsom is grappling with a welter of complex problems: climate change, raging wildfires and the challenges of the pandemic. Still, he added, “many of the things that should be talked about are kind of getting swept under the rug.”

For Lorna Roush, who manages Schultz Ranch in Fresno County with her father, brothers and children, the worry that water will be scarce when she eventually takes over the farm has added to her concerns about Mr. Newsom. Her family has tried to make plans for a potentially sharp reduction in water supply; they already minimize their usage, she said, and have made adjustments to their farming practices.

“Governor Newsom has had the chance to dig into this, research it and understand what the policies are doing to California agriculture, and he’s not doing anything about it,” said Ms. Roush, who declined to say how she voted. “We’re always worried.”