He frequents 19 of them but it has nothing to do with grabbing a cold one after a long day of milking cows. Instead, he makes weekly stops to pick up something the brewers no longer want: spent grains that remain from creating some of the area’s trendiest microbrews.

On an average week, Konyn collects about 225 tons of the grain that serves as protein-rich feed for his nearly 900 milking cows. He has plenty left over for a nearby dairy farmer’s herd.

Konyn began hauling the unwanted byproduct in 2009 with a pickup truck. Today, he owns five semi-trucks and 40 “roll-off” containers that are 18 feet long and are left at each brewery to be filled.

“The brewers know their waste stream is being upcycled and not contributing to filling up landfills,” Konyn said. “We’ve taken care of their headaches and created a win-win situation. It makes them proud and gives them a story they can tell.”

The more than 31,000 dairy farm families in the U.S. also have a story to tell, and the timing couldn’t be better to share it. Climate change is top of mind for consumers and is especially high on the radar of younger generations. A YPulse Sustainability Report of Gen Z and Millennial audiences (13- to 39-year-olds) finds two in five young people worry about climate change every week.

They expect industries to do the right thing for the planet. The good news is dairy farmers have been caring for the environment long before the term sustainable hit the mainstream. Though there’s still work that needs to be done, farmers haven’t always talked about the progress they have already made.

Frank Mitloehner of University of California, Davis, works with dairy farmers to maximize on-farm efficiencies.

But Frank Mitloehner, Ph.D., a professor and air quality specialist at University of California, Davis who has worked closely with dairy farmers across the country, will happily do so on their behalf.

“We have seen changes in the U.S. dairy industry that are astounding,” Mitloehner said. “They are the envy of the world, but for whatever reason they are painfully quiet about it.”

Citing Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data that helps put to rest the idea dairy and other aspects of animal agriculture are major greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters, Mitloehner said there are three sectors that produce nearly 80% of all GHG emissions in the U.S.: transportation, power production and industries.

According to Mitloehner, The EPA found all species of livestock, including the feed sector, produce only 4% of all greenhouse gases.

“But there are people out there who will claim there is nothing worse and more environmentally detrimental than the livestock sector,” he said. “That clearly is not supported by fact, it’s not supported by science.”

Cows: The Original Recyclers

Juan Tricarico, Ph.D., vice president of sustainability research at Dairy Management Inc., an organization that grows sales and trust on behalf of U.S. dairy farmers and importers, says the nation’s 9 million lactating dairy cows play a starring role in dairy’s environmental success.

Tricarico understands quite well what makes cows tick. He earned his doctorate degree in dairy cow nutrition, which has consumed his world for the last 25 years. That’s why he gets rather excited – borderline geeked out – when he speaks about a cow’s ability to take food humans can’t eat and convert it into something they can: milk.

Tricarico authored research that shows 80% of what dairy cows eat can’t be consumed by people. This includes byproducts such as those Konyn collects from microbreweries and others, such as almond hulls, cottonseeds, citrus pulp and peel, and corn grain remaining from the production of ethanol.

Tricarico describes the cow’s digestive system as “this amazing community of microbes that are an entire ecosystem inside the belly of the cow.” He says bacteria, archaea, fungi and protozoa work in a way that puts the cow in a class of its own when it comes to digesting abilities.

“The rumen ecosystem includes thousands of microbial species and is equivalent in its complexity to the tropical rain forest,” Tricarico says. “Dairy cows can eat fairly rough plant material, and they can eat a lot of it because they have a big rumen with the ability to digest it all.”

Understanding Methane

The cow, however, sometimes gets a bad rap. “Cow farts” are blamed as a primary cause of climate change, but Tricarico falls back on Biology 101 to offer clarity. When cows ingest feed, microbes ferment it in the rumen first.

“The microbial fermentation occurs closer to the mouth; therefore, the methane is primarily released from the mouth, not from the back end,” Tricarico says.

Mitloehner adds to Tricarico’s point with more methane facts. He said there are three main greenhouse gasses: carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that all differ in how they trap heat from solar radiation. But he said what isn’t talked about enough is that carbon dioxide has a lifespan of 1,000 years, while methane has a lifespan of 12 years.

“So that means any kind of carbon dioxide we put into the air through any of our activities is still there,” Mitloehner said. “Every day you drive your car, you are adding new CO2 to the atmosphere. That’s different from methane because while it’s also emitted, it’s also destroyed, and it’s destroyed at a very high rate through a process called oxidation.

“This is critical for animal agriculture because roughly the amount of methane being produced every year almost equals the amount of methane that is being destroyed every year globally and nationally.”

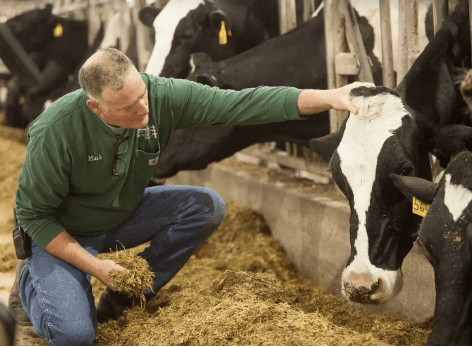

Cows are able to turn byproducts of human food production into milk, thanks to their unique digestive systems.

Measuring Dairy’s Environmental Impact

David Darr serves as senior vice president, chief strategy and sustainability officer at Dairy Farmers of America (DFA), the country’s largest cooperative with more than 13,000 dairy farmer members. Darr said a “lightbulb just kind of came on” following a life cycle assessment (LCA) the U.S. dairy industry conducted in 2008.

The LCA focused on fluid milk and showed the industry accounts for:

- less than 2% of total GHG emissions in the U.S.;

- 5.1% of water use;

- and 3.7% of U.S. farmland.

Meanwhile, on the farm, the environmental impact of producing a gallon of milk in 2017 shrunk significantly from 2007, requiring:

- 30% less water;

- 21% less land; and a

- 19% smaller carbon footprint.

Darr said the dairy LCA – the first in food agriculture at a national scale – allowed the dairy community to begin speaking about sustainability more quantitatively than qualitatively when talking about dairy sustainability.

“Historically, it was ‘We take care of cows because they take care of us’ and ‘We take care of the land so it’s around for the next generation’ but how do we measure that?” Darr said. “How do we validate that and communicate that? Normal farm practices [that have been done for years] evolved pretty quickly into ‘sustainability.’”

Yet even the smallest emissions can still have an impact on the climate. That’s why the U.S. dairy industry in 2020 announced its most pivotal and public commitment to the planet.

The Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy, an organization that works with leaders from across the dairy value chain to align on pre-competitive priorities, drive progress and advance a shared social responsibility platform, developed the 2050 Environmental Stewardship Goals. By 2050, U.S. dairy collectively commits to:

- Become carbon neutral or better.

- Optimize water use while maximizing recycling.

- Improve water quality through enhanced manure and nutrient management.

The Innovation Center – along with five other national dairy organizations – followed with the announcement of the Net Zero Initiative (NZI) as a key pathway on farm toward achieving the industry’s collective goals. Its aim is to create a world where dairy is a solution for today’s nutrition and environmental challenges. NZI will enable dairy to provide accessible and affordable nutrition while sequestering carbon and improving soil health through improved land use systems; reducing GHG emissions through feed management, manure management and energy efficiency; and generating renewable energy that can cleanly power vehicles, homes and businesses.

NZI can be a fit for all U.S. dairy farms, and some of the world’s most recognized brands have taken notice. Nestlé and Starbucks recently announced they are providing financial and technical support and expertise in helping famers find their path toward net zero.

Karen Scanlon, executive vice president of environmental stewardship for Dairy Management Inc., runs point on NZI and is excited the initiative will provide further proof that dairy is produced responsibly.

“We fully believe that all farmers – regardless of size or geography –– are already doing something that contributes to progress and will help our industry reach our environmental stewardship goals,” Scanlon said. “Dairy farmers’ values, progress and long-standing commitments are the reason we can set aggressive goals and be leaders in sustainably nourishing people and the planet.”

NZI will document farmers’ efforts, such as producing renewable energy from wind and solar, as well as anaerobic digestion. It also will track other energy-saving measures, such as LED lighting installed in barns or switching to high-efficiency refrigeration used to instantly chill milk at the farm. Practices in the fields, such as minimal disturbance tillage, cover cropping and buffer strips, are also ways farmers reduce their GHG emissions.

Different practices work for different farmers, so they can tailor what works for their region and climate.

Adapting Game-Changing Technologies

Some practices are pretty high-tech. Varcor may top the list.

Varcor was created by Peter Janicki of Sedron Technologies and gained attention when the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation used a similar technology to process human waste into safe, drinkable water for developing nations.

It so happened Janicki’s wife has roots in the dairy community and conversations started about how this technology could be applied to the industry. That’s when Donald and Cheri De Jong, who own Natural Prairie Dairy Farms in Texas and Indiana, and another farmer met with a team of Janicki’s engineers to explore the possibilities.

Varcor offers more than a clean water solution for dairy farmers. Using a process called vapor recompression and distillation, cow manure that has been mixed with water from cleaning dairy barns is piped into the Varcor system where it reaches a near boiling point. It then is dried and scraped. The finished product is an odorless, concentrated nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK) fertilizer.

While the water runs clean, it has yet to be approved as safe by the Food and Drug Administration for human or animal consumption, but it finds a second life nourishing crops that are grown to feed the De Jong’s cows. The system also produces another byproduct: aqueous ammonia, which is high in nitrogen and can be injected into the ground as additional crop fertilizer.

Varcor ultimately would eliminate the need for manure storage lagoons on some dairy farms while greatly decreasing methane emissions. It also would reduce or eliminate tractors, dump trucks and fuel used for handling manure.

Cheri De Jong said she figures Varcor can produce up to 20 tons of NPK solids daily from the farm’s 3,000 cows in Indiana.

“This is a game-changer,” she says. “We’ve gotten more calls and e-mails about dairy farmers’ interest in this. They see opportunities out there, whether it’s Varcor or other technologies. They are looking at things differently because sustainability is the key to our future in dairy farming.”

Community Collaboration Turns Waste Into Energy

Washington dairy farmer Jim Werkhoven understands sustainable practices can change the course of business for the better. His family operates two dairies in the Cascade Valley town of Monroe, about 30 miles northeast of Seattle. The farms are at the confluence of the Skykomish and Snoqualmie rivers in a setting fit for Instagram. Werkhoven’s goal is to preserve the pretty picture by avoiding a potential manure runoff caused by the family’s 2,000 cows.

Jim Werkhoven’s digester in Washington converts his community’s waste into enough electricity for about 300 homes.

The rivers are sacred to the nearby Tulalip Indian tribe, which has used them as a source of drinking water and salmon harvesting for generations. About 20 years ago, conversations began regarding enhanced water protection measures supported by the Tulalip that would have a dramatic impact on management practices at Werkhoven’s farms. His family and other valley farmers became worried.

But instead of letting matters become heated, the farmers met with tribe leaders, a salmon recovery group and local officials.

“They educated us on some of the problems they have with salmon recovery, and we educated them on modern agriculture practices,” Werkhoven said. “We decided we need to figure out a way to do something collectively. Our values are not that dissimilar that we can’t work together.”

The group identified about 300 acres of state property where a prison farm once operated. A legislative act then deeded the land to the tribe with a provision it remains in agriculture. This led to the construction of a methane digester in 2008. Cow manure now leaves Werkhoven’s dairies and is fed into the digester along with waste from the Tulalip community. And, to borrow Werkhoven’s description, “gunky” material makes its way there from local businesses.

He said there is a “cottage industry” of people who collect remnants from fish processing plants and slaughterhouses as well as used cooking oil from restaurants’ deep fryers arrive by the semi load.

“It’s real ugly stuff,” Werkhoven says. “This is the stuff sewer plants hate and landfills struggle with because it’s liquid. Twenty-five years ago, it was going down the drain.”

But the digester’s microorganisms work their magic and convert about 22,000 gallons of the assembled waste daily into methane, which powers a 450-kilowatt generator. This produces enough electricity for about 300 homes.

“The digester has been successful, but honestly the biggest success is a good working relationship with the tribe,” Werkhoven said. “Things sometimes seem like they need to start with a fight in agriculture. In our experience it showed you’re going to be more productive if you work together. The tribe has been a super partner and being partners is a whole lot better than being enemies.”

Across the country, a digester project in Florida also is primed to make an environmental impact. Chevron U.S.A and Brightmark have partnered on projects that will produce renewable natural gas (RNG) from biomethane captured at dairy farms through anaerobic digesters. The raw biogas is processed before being injected into local, state or interstate pipelines. Many businesses depend on natural gas for cooking, steam production, water heating, power generation and other uses.

Larson Dairy in Okeechobee, Fla., became a partner with the project last fall. It’s expected to annually convert 230,000 tons of manure from 9,900 cows into RNG.

The patriarch of the family’s dairy, Louis “Red” Larson, was involved with discussions of the project but passed away at 96 before seeing the work finalized.

His grandson, Jacob, said one of his grandfather’s favorite sayings was “do the right thing.” Those words were echoed by Jacob during a groundbreaking ceremony at the dairy last November.

“The Larson family feels this is the right thing,” Jacob said. “It’s the right thing for our future, it’s the right thing for sustainability.”

Elsewhere, Vanguard Renewables, one of the country’s leading food waste recyclers, has partnered with Dairy Farmers of America, Unilever and Starbucks to form the Farm Powered Strategic Alliance. Its goal is to reduce food waste from manufacturing and the supply chain and repurpose unavoidable waste that cannot be eliminated into renewable energy via farm-based anaerobic digesters.

“Dairy is really demonstrating the goodness we can do,” DFA’s Darr said. “Some of the country’s largest brands and companies are coming to dairy and asking us how we can collaborate with them. They’re doing it because of the reputation and track record that dairy is establishing around how we believe we can be part of environmental solutions and how we’re willing to have a dialogue to see how we can go beyond what we know and be part of unique, cutting-edge projects.”

Education plays a role

Farmers, such as Michigan’s Annie Link, have grasped the importance of dialogues, especially with consumers who are a couple of generations or more removed from the farm and food production. This gap inspired her family to create the Dairy Discovery program, using their farm as a destination for field trips, camps or for anyone else interested in learning about modern agriculture practices.

The conversations begin with a history lesson. SwissLane Dairy Farms was founded by Link’s great-grandfather, Swiss immigrant Fredrick Oesch, 105 years ago. He no doubt chose the location because a creek runs along the backside of the farm’s 90 acres where his cows could grab a drink of cold water and continue crossing into a field to graze.

The cows no longer wade into the creek, which today provides more sentimental purposes for Link. It’s a Mother’s Day tradition for her husband, Jerry, to take her trout fishing there.

“He knows all the best spots,” Link says. Whatever they catch, Jerry cooks. A couple of years ago it was her best catch ever: an 18-inch brown trout.

Annie Link of SwissLane Dairy in Michigan started an education program for anyone interested in modern agriculture practices.

Fishing aside, having a dairy that close to the water comes with added expectations from a magnified public lens that the farm does all it can to preserve the water’s integrity.

That motivated the family to further show its commitment to the environment. One goal was to become verified through the Michigan Agriculture Environmental Assurance Program, a state-based tool to prevent or minimize agricultural pollution risks.

During the review process, the farm was told one of its barns was too close to a steep hill, increasing the potential for runoff to enter the creek should a torrential downpour occur. So, in 2007 the family constructed a modern barn built further from the creek. This earned the dairy its verification, and it later received similar acknowledgement for its cropping efforts.

SwissLane also partnered with the Coldwater River Watershed Council to conduct tests on the health of the water and its fish. The results showed high water quality and healthy fish – and no concern the farm and its cows were impacting its integrity.

“Maybe it’s because the dairy is here that we have healthy fish and clean water,” Link said. “I always ask kids on our tour if they think the creek was cleaner now or in 1915. They always say 1915, but we have the facts that it is a renowned trout creek and it’s cleaner now.”

Back in San Diego, Frank Konyn farms under an even brighter spotlight. San Diego is the eighth-largest U.S. city with 1.4 million residents. He said there was a time when the county had more than 200 dairies. Now, he’s one of two remaining.

It may be why he’s always gone above and beyond to be a good neighbor. Around 2007, he began placing a pile of manure near the front of his dairy where people could take what they wanted for their home gardens. A donation box sat nearby for them to leave a few bucks if they chose.

“You’d check the box once a week and say, ‘Holy smokes, someone left a $10 bill in there!’” Konyn says.

From those humble beginnings, Konyn, 48, has built a composting business that requires much more than a donation box. He partners with large landscaping companies to take their green waste and trimmings. It’s mixed with his cow manure and results in 27 composting products available in the marketplace.

“Once again, it’s a story of material that would have ended up in a landfill now being diverted and composted with cow manure,” Konyn said.

It begs the question: Is Konyn a dairy farmer first and environmental entrepreneur second or vice versa?

“It’s a great question,” he says. “The dairy is like the mothership with all of these satellites around it, but the satellites wouldn’t exist without the mothership. I have a vision of what this place will look like when I’m 65, and right now I’m just assembling the pieces of the puzzle.

“Hopefully when I’m 65 someone will say, ‘He put together a hell of a show and it’s a viable enterprise and he’s doing the right thing for the environment. Let’s hope it continues for the benefit of the citizens of San Diego.’”