More than 1,100 Minnesota dairy farms closed up between 2012 and 2017, leaving only about 3,600 farms in an industry beset by years of low milk prices and a long, hard winter that delivered enough snow and wind to collapse the roofs of at least two dozen dairy barns.

The Minnesota Legislature passed the $8 million Minnesota Dairy Assistance, Investment and Relief Initiative (DAIRI) this year, in response to crisis in the dairy industry in Minnesota, the seventh-biggest dairy producer in the United States.

While an influx of cash could help, dairy industry watchers are looking toward the future with trepidation.

A string of lows

The state the dairy industry’s in is nothing new — and that’s the problem. For dairy farmers, a 5 percent profit margin is considered a good year, said Lucas Sjostrom, a dairy farmer and the executive director of the Minnesota Milk Producers Association. Lately, lots of things have been eating away at those profits.

Like farmers in any ag sector, dairy farmers’ income depends on a lot of things that are outside their control: weather and international commodity prices among them. Farmers are used to some degree of price fluctuation year-to-year.

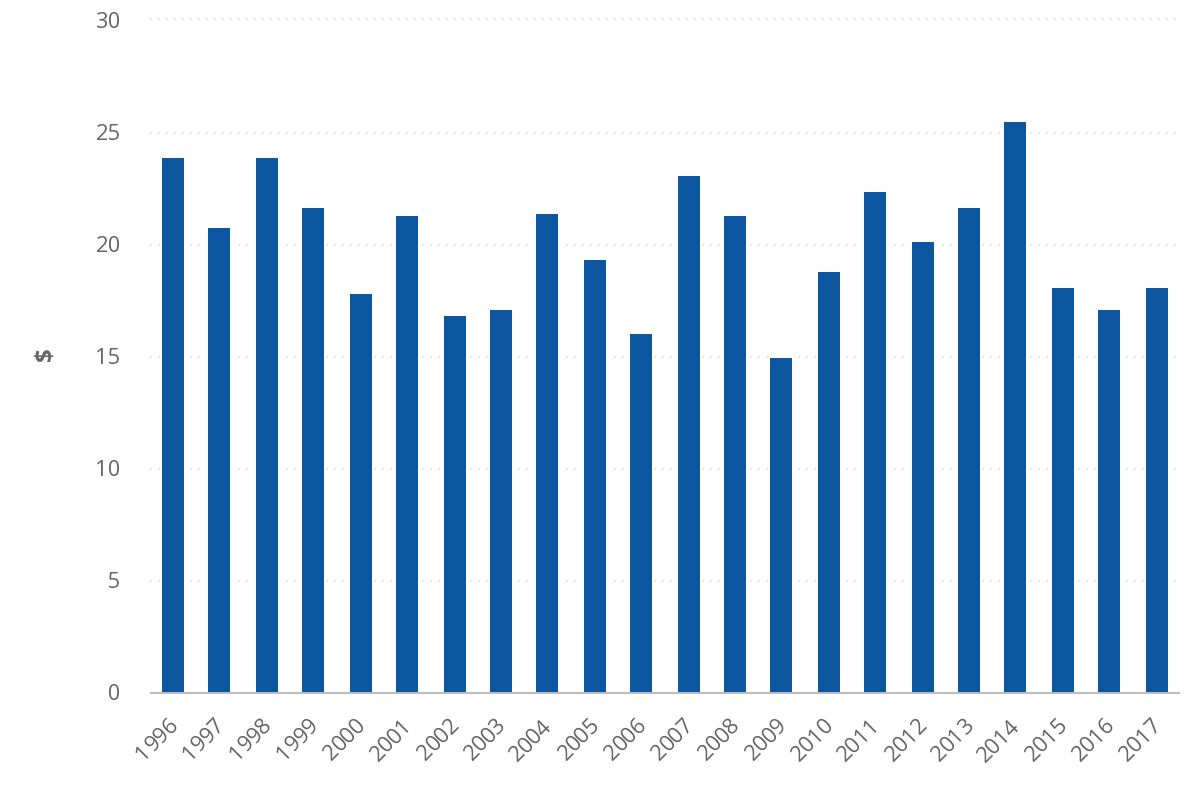

The dairy industry was on a fairly consistent three-year cycle from the early 2000s, with good prices every three years or so. Until it wasn’t. In 2015, dairy prices smashed records. Then, prices stayed low for a couple of years. Dairy industry watchers thought things might look up in 2018. And then they didn’t.

There are lots of factors keeping milk prices down, on both the supply and demand sides.

On the supply side, there’s more milk on the market. By breeding for specific traits — higher milk yields and healthier cows — production in the dairy industry has become more efficient and milk more plentiful. That can put downward pressure on prices.

At the same time that it’s easier to produce more milk, demand for U.S. milk products is down, both domestically and abroad. Americans are drinking less milk, and trade disputes in recent years have shrunk global markets for U.S. dairy.

In 2017, Canada changed its pricing system, decreasing the cost of a specific milk type domestically, which made U.S. milk used for the same purposes too expensive to reasonably import.

Then came the tariffs. From both Mexico, the U.S.’s No. 1 dairy export market, and Canada, its second largest market, Sjostrom said.

“It’s been a tough year, but the only reason it has been a tough year is because it’s been a tough roughly four and a half years,” he said.

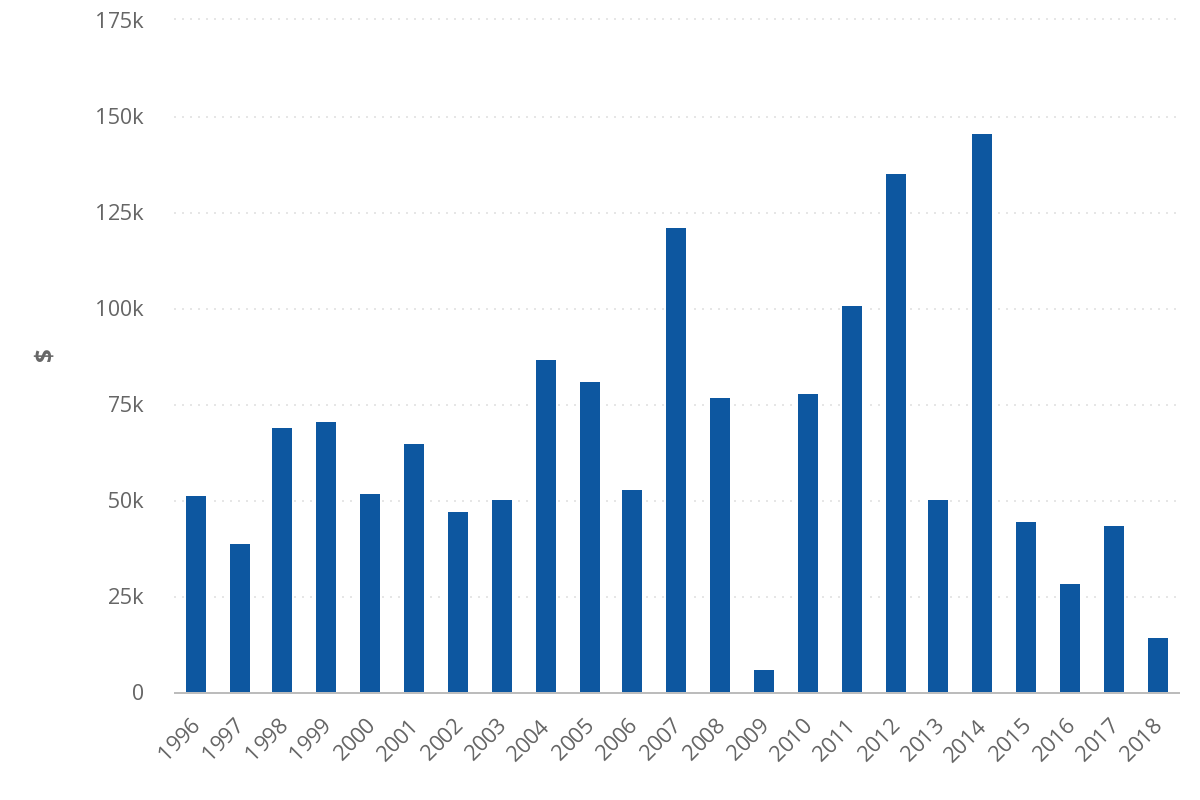

In 2018, the median Minnesota dairy farmer made $14,700 — the smallest median annual income in a string of lows, according to the most recent year of data available from the Minnesota State and University of Minnesota Extension farm income survey.

Last year, 50 percent of dairy farmers surveyed reported a negative net farm income, and the average dairy farmer lost about $29 per cow, said Joleen Hadrich, an associate professor and extension economist at the University of Minnesota who specializes in the dairy industry.

“Prices really haven’t recovered since then, so that’s something on our forefront. We know farmers are really becoming financially strapped. They may have been able to dip into their cash reserves, if they had any, but those opportunities are really bottoming out,” she said.

DAIRI

Enter DAIRI. The new Minnesota program, designed for small and medium-sized farmers, became available last week. To be eligible, farmers have to produce less than 160,000 hundredweight of milk (a hundredweight, the unit of measurement used in the dairy industry, is 100 pounds). That’s what about 750 cows can produce, and would cover most of Minnesota’s dairy farms, said Paul Hugunin, of the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s Ag Marketing and Development Division. Farmers also have to sign up for five years of coverage under the new federal Dairy Margin Coverage program in order to be eligible for the state program.

The Dairy Margin Coverage program, authorized in the 2018 farm bill, is like crop insurance for dairy farms: Farmers pay a premium each month, and the federal government will send farmers a check to make up some of their losses if prices go below a certain level.

The state program is designed to work in concert with the federal program. It would pay 10 cents per hundredweight of milk, up to 50,000 hundredweight.

Hadrich estimates a farm with 100 cows would get about $8,000 from the federal program this year. Minus the cost of their premium, including a discount for signing up for the state DAIRI program, such a farm would net about $5,700.

The farm would get about $2,000 from the state DAIRI program, which would bring it up to $7,700. Add that to the $14,700 median dairy farm income last year, and that farmer’s hypothetically making $22,400.

It’s not designed to make farmers rich, but it might help cover a feed payment and keep some farms afloat.

“These programs are not meant to be profit maximizers; they’re very much meant to be revenue stabilizers,” Hadrich said.

If there’s money left over after the state makes initial payments from the DAIRI fund, qualifying farmers will get another check, of an indeterminate amount, in the fall.

Sign-up at local Farm Service Agencies started last Monday, and by Tuesday, the state already had its first application for DAIRI.

“This particular program, from a state level, is the state trying to help bridge that gap between where we are today and when things improve,” Hugunin said. “We need to make sure we can help farms weather the storm, so to speak, and survive to see better days.”

Better days ahead?

It’s not yet clear when the markets will improve.

Dairy farmers necessarily have to look years ahead as they make plans for the season: It takes two years for a calf to grow big enough to have a baby and start producing milk, and it’s five years from birth until a farmer gets a return on investment out of her, Sjostrom said.

“You’re basically making a five-year plan every time a calf is born,” he said.

For some, that future looks uncertain. One big question is what the price of corn and soybeans, used to feed cows, will be in the future. Bad weather this year may well drive them up, while tariffs could bring them down.

And there’s another wild card: Swine fever in China has killed a large share of that country’s pigs. On one hand, for dairy farmers, that’s depleted the market for whey permeate, a milk product shipped to China to feed piglets.

On the other hand, fewer pigs in China . could increase demand for U.S. beef abroad, another source of profit for dairy farms. Dairy farmers typically make 10 percent to 15 percent of their income on beef — selling calves to become steers and dairy cows who age out of production for meat, Sjostrom said.

“There’s only so much protein in the world, so when people buy less of one type of meat, they buy others,” he said.

As the daughter of dairy farmers in Central Minnesota, Hadrich said it’s in their nature to be optimistic.

“I think there’s a lot of people who want to stay in dairy and they’re trying to find creative ways to stay in the industry,” she said. “For a lot of them, this is a way of life.”