On a hot July day, cattle farmers Jesus Hurtado and Dirk Rietsma welcome a delegation of international visitors to Suntado, their soon-to-open dairy processing plant in Idaho’s Magic Valley. The visitors include the Chinese official who serves as official emissary to the western state. For the life-long dairymen, her presence is a key step to realizing their $150 million dream of shipping their milk around the world.

Most of Idaho’s 500 family-owned dairy farms sell locally—or as far as the milk can go before it is processed or spoils. Hurtado and Rietsma are taking a different tack: They invested in 18 aseptic production lines that extend the shelf-life of milk from about two weeks to 12 months. The change means the two farmers, who collectively produce about 100 million gallons of milk a year, can now seek out new markets across the globe.

China is only the third largest importer of American dairy, after Mexico and Canada, spending $607 million last year. But, considering the changing cultural attitudes towards dairy, it also represents one of the largest growth opportunities. According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, China consumes about 15% of what Americans consume per capita. If that gap closes China would add more than $600 billion to the global dairy market.

Even amid rising geopolitical tensions, the U.S. and other countries are fighting for a slice of that…cheese. China’s minister of international trade, Wang Shouwen last month invited American dairy firms to set up shop in China and the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced a $1.2 billion investment in dairy exports. Some of the largest banks in America are already financing a $7 billion dairy boom, and private equity is starting to take note.

“Protein is a building block of life,” said Reitsma, speaking from Sunrise Organic Dairy in Paul, Idaho, where he tends to 10,000 cows. “And a lot more people are realizing that the whole dairy protein is as good as you can get, better than anything else that we consume.”

Tainted milk, broken trust

The Chinese dairy investment opportunity goes back sixteen years, according to David Ettinger, a food safety lawyer at Keller and Heckman, whose clients include candy giant Mars and and plant-focused Impossible Foods. Amidst conflicting reports on whether the disparity between Chinese consumption and most the rest of the world might be based on a genetic difficulty processing dairy, Ettinger blames it on insufficient regulation.

In 2008 the Chinese government seized tainted milk from more than 20 companies, leading to a global freeze on many Chinese food imports. The seizure only came after the poisoning of multiple children, making consumers wary of purchasing local dairy. China’s government mounted an aggressive response, which included the execution of two corporate executives. But it was too late, and Ettinger says many Chinese shoppers still choose to spend more rather than buy local.

It wasn’t until ten years after the scandal, in 2018, that China started publicly fighting for global dairy market share. That year the state council, the highest administration in China, published a report on how to revitalize the dairy industry. “That was when I first started to see China put some focus on encouraging dairy,” says Ettinger during a recent trip to D.C. “Because if they push the dietary intake of dairy, the consumers are not going to buy it, unless that trust comes back, and it was damaged for almost a decade.”

Between 2017 and 2022 China’s dairy consumption increased slightly from 30.4 million metric tons to 39.3 million metric tons, according to a Rabobank report from last year, and is on course to grow by an average compound annual growth rate of 1.5% by volume, reaching 62.2 million metric tons in 2032. If China consumed the same amount of milk per capita as the United States, it would consume 326 million metric tons. At todays prices, converted to U.S. dollars, that would be worth $626 billion.

“Pizza has become their lunches and dinners,” writes Tara Qu, China’s chief representative to the State of Idaho, in an email to Fortune. “However, China’s import of dairy products has reduced in the recent years.” The Rabobank report predicts an 8% drop in imports, due largely to increased local production.

Leading the fight for that market share is New Zealand, with 42% of the market last year, followed by 13% from the U.S. and 11% from Germany. While New Zealand and Europe are both integrating stringent sustainability measures into their dairy rules, American regulations are much more lenient, according to Wells Fargo economist Tim Luginsland. “They’re not expanding due to the carbon footprint etcetera,” says Luginsland “And we are continuing to build out.”

Milk goes high tech

Based in Burley, Idaho, the roots of the Suntado dairy farm go to back to 1986, when Jesus Hurtado immigrated from Casacuarán, Mexico and learned the trade at Reitsma Dairy, the farm owned by Dirk’s father, John. Hurtado proved himself so adept at the job he ended up buying the farm, and rebranding it Hurtado Dairy, which manages 30,000 cows. In 2013, Reitsma bought his own dairy, 30 miles away.

The old friends turned friendly competitors grew tired of shipping so much of their value to third-party processing plants and hatched a plan to personally invest $45 million as collateral to borrow $150 million from New Jersey-based BMO Harris.

Though regional banks still finance most American farms, it’s the new technology at these processing plants that gets large American banks’ attention. Not only do the plant’s aseptic production lines extend the shelf-life of milk, but they also let the dairymen keep the tolling fees—the cost to process and package the milk—they’d otherwise be paying others, generating an estimated $300 million revenue the first full year of operation, says Reitsma. By the time the company is fully operational it’ll employ 300 people and generate more than $1 billion revenue.

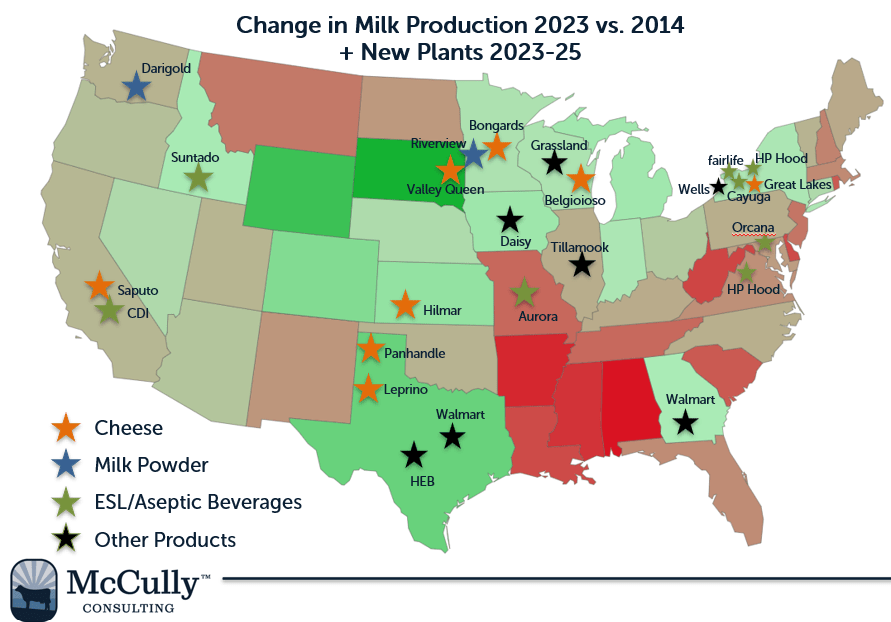

The upstart farmers are competing with some of the largest dairy companies in the world. Coca-Cola’s dairy production service fairlife is building a $650 million plant in Webster, New York, and earlier this year added a new line of “high nutrient milk” to its China line. Seattle-based Darigold is building a $600 million facility in Washington, selected specifically because of its proximity to the Columbia River, and streamlined access to China.

Big business

The dairy boom is largely being financed by five commercial banks: Bank of America, the Bank of Montreal, First National of Nebraska, U.S. Bancorp, and Wells Fargo, the largest bank investing in American dairy, according to data from financial research firm Stephens. Though Wells Fargo declined to share its total capital invested in dairy, its Minneapolis-based executive director, Josh Villas, has more than $1 billion allocated to dairy companies with revenue between $500 million and $10 billion. He says the single most popular reason dairy companies borrow money is to expand.

Private equity firms are also paying attention. Over the past year alone, Platinum Equity, Altamont Capital Partners and Osprey Capital have all bought U.S. dairy firms. In 2021 KKR invested in Adopt-a-Cow, a Beijing-based dairy firm. Villa’s latest financing round, in Minnesota-based Milk Specialties Global, caught the attention of PE firm Butterfly, in part because it opened up dairy markets in China and other nations.

Silicon Valley venture capital firms are also looking to get a piece of the Chinese dairy market. In 2021, Sequoia Capital affiliate Sequoia China invested in Chinese yogurt company, Simple Love and reportedly bought a 15% stake in Junlebao Dairy Group, for $170 million. Earlier this year, though, geopolitical tension forced the affiliates to part ways, leaving most of the Chinese assets in China. Though a letter signed by members of Congress expressing concern over the separation didn’t explicitly mention dairy, it speaks to lack of trust between the nations.

Meanwhile, Georgia state representative Mike Collins has warned that China owns 384,000 acres of American agricultural land, calling it a threat to national security. Even as China’s international trade representative Wang Shouwen welcomed U.S. dairy companies to the Chinese market, he warned that U.S. tariffs on China could result in “severe potential consequences on U.S. companies in China.”

“The U.S. and China aren’t really on the best of terms right now, and that likely won’t improve in the future, at least for a while,” says Mike McCully, a consultant focused on dairy and food companies. “This isn’t to say U.S. companies that have sales offices in China won’t be able to grow sales, they will. It’s just that there are a number of challenges to work through.”

Back at Suntado, Reitsma and Hurtado processed their first dairy truck last month, and the first phase of the build is already operating at full capacity. Going forward, the expansion will include 12 more production lines, tripling capacity, and finally opening up access to their first overseas clients. Reitsma says they’re currently in discussions with multiple companies in China and hope to enter the nation next year. “Their palate is changing,” he says. “And they’re seeing the health benefits of milk.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K