The pegs were not holding socks or shirts that needed to be dried. Instead, each plastic peg gripped onto a clutch of bills. One held bills more than 60 days late, another peg those more than 120 days late, while a third with bills yet to reach their due date.

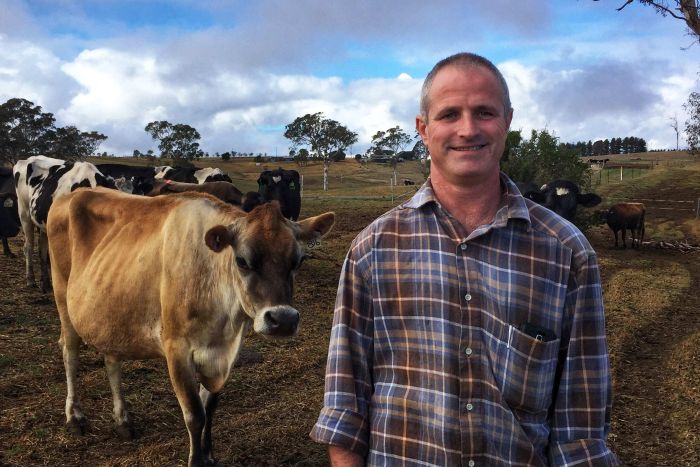

For the leader of one of Australia’s biggest agribusinesses, himself a dairy farmer until just a few months ago, it was another telling moment of the severe drought hitting farms and hurting agribusinesses across the country.

While Roberts wasn’t observing a problem on a production line at a Bega factory, the challenges faced by struggling dairy farmers such as steep feed costs, vast electricity bills, veterinary costs and hefty council rates flow directly through to dairy companies such as Bega.

Fast-rising costs are occurring at the same time as many dairy farmers have sold off some of their cows simply to make ends meet, reducing their ability to earn ongoing revenue from supplying milk.

“The thing that really hits home is when they bring out two or three clothes pegs jammed full of accounts they can’t pay. That’s the one that hits home then, and you just see the desperation,” Roberts says.

To secure the right amount of milk to keep its factories running at optimum, dairy company Bega this week announced an increase in the prices it pays farmers for their milk. At the same time it delivered a profit warning in relation to its 2020 earnings – the drought was mainly to blame.

Increased business costs squeeze margins, and Bega advised the market that its 2019-20 normalised EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) would be $95 million to $105 million. This is down from last financial year’s $115 million result.

In part, the decision to pay higher payments for milk reflects the fact that Bega is playing a long game.

“We’ve always said that we wanted to maintain the milk supply because you’ve got to take a long-term outlook on this,” Roberts tells The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald.

“Because if you can maintain the milk supply, keep the farms in business, in the long term it’ll pay dividends.

I think everyone needs a drink, that’s just the reality of agriculture across Australia at the moment. It’s horrendous.

Hugh Killen, chief executive of Australian Agricultural Company

“If you’ve got stainless steel and you’ve got brands and you’ve got markets, you can’t afford to lose them. You’ve invested heavily in those and that investment has to be protected, and you need the milk,” he says.

Corporate kryptonite

The current drought started in 2017, with northern Australia experiencing a “failed” wet season over the summer of 2017-18. Drought conditions have steadily worsened in Queensland and NSW, the two worst hit states, in the period since. Parts of Victoria are also in drought, while other parts including northern Victorian dairying regions are facing severe seasonal conditions.

The Morrison government has spent more than $2.5 billion in various drought assistance packages and has quarantined $5 billion for a future drought fund. The fund will distribute $100 million a year, beginning next July.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison said this week the drought response would continue to evolve and promised “more measures soon”.

For some of Australia’s listed agribusinesses, the drought has been like corporate kryptonite.

Bega’s profit warning came less than 24 hours after fresh produce giant Costa Group, the country’s biggest grower and marketer of fresh fruit and vegetables, unveiled its fourth profit warning of 2019. Investors in the companies reacted swiftly to the downgrades, sending their shares down sharply.

Costa Group cited a range of issues behind the downgrade, with the combined effect of severe drought and extreme heat among the major reasons. Drought has pushed up its water costs, while severe heat has hurt crops – affecting size, yields and prices.

“This drought’s gone longer and deeper than most people, most observers would have thought,” Costa chief executive Harry Debney said this week.

Asked where the business would be if the country had experienced normal seasonal conditions over the past year, Debney said Costa would “be in good shape”.

The hot conditions have slowed plant growth and led to smaller avocados, blueberries and citrus fruits. And in horticulture, smaller fruit typically equals smaller prices.

“It is true to say that agriculture has a higher degree of volatility than other sectors of industry. We’ve done a lot of work to mitigate that with protected cropping and putting more technology into high-tech glasshouses,” Debney said.

If you can maintain the milk supply, keep the farms in business, in the long term it’ll pay dividends.

Max Roberts, Bega Cheese chairman

“We’ve done that but we are not immune, we are not immune at all from a lot of the vagaries of temperature and drought. So I think people have got to weigh up agriculture, even if you like a more technologically-based agricultural company it has still got a risk factor or a set of risk factors and the market I think has got to make its judgment on that,” he said.

The Australian Agricultural Company, or AACo, was established in 1824 so knows a thing or two about droughts; it has seen plenty of them.

AACo is the country’s largest cattle and beef producer with huge operations in the Northern Territory and Queensland. It has felt the severity of the current drought in both states.

The company has cattle across about 6.4 million hectares of Australia, and because of drought is having to buy plenty of feed. Feed grain is now costing about $415 per tonne; this time two years ago it was about $320 per tonne.

The big dry has also pushed up AACo’s trucking and fuel costs, as it has had to move large numbers of animals around to find better conditions.

“It (the drought) is having a broad impact across a couple of areas,” says chief executive Hugh Killen.

“Number one is, our cost of production is clearly going to be higher given we’re a large feeder of cattle. So as the drought bites, commodity input costs into businesses like ours get extremely tight,” he says.

AACo, which is set to release its half-year results this month, was whacked by climatic events in the 2019 financial year. Then it said drought-related costs totalled $60 million, while a huge flood event in Queensland’s Gulf region at the beginning of 2019 killed about 43,000 cattle and cost about $47 million.

The severe impact of drought last year led to significant planning by AACo in anticipation of continued drought.

AACo has sold cattle more aggressively and reduced the size of its herd with an eye on both strong cattle prices and long-term weather forecasts. It also planted a vast amount of hay and so far this season has cut about 18,000 tonnes of it to feed livestock. It has plenty left to cut.

“We’ve got a significant amount of hay available to us, whereas others can’t actually afford or get hold of hay,” Killen says.

Another thing buttressing the company is the price of beef, with strong demand for beef from key markets such as the United States and China lifting prices.

“Global meat prices are extremely high at the moment. So you’ve got probably one of the biggest bull markets that we’ve seen in red meat, probably ever,” he says.

AACo may be sitting on a very good beef price and a hefty pile of hay, but Killen says all of the northern beef industry needs a “significant” wet season, expressing hope that forecasts for a late start to the wet season are wrong.

“I think everyone needs a drink, that’s just the reality of agriculture across Australia at the moment. It’s horrendous,” he says.