Brazil, South America’s largest country, is largely self-sufficient in dairy supply.

The last three years have seen major changes in prices of goods and services worldwide and Brazil is no exception. While some important dairy farming inputs like fertilisers and concentrates have now come down, others like herbicides, seeds, and fencing equipment have not.

To understand what is happening in the Brazilian dairy industry one must first remember (a) farmers are paid by the litre; (b) the average farm operation is very small by New Zealand standards (110,000-274,000 litres/year), and extremely diverse (ranging from 18,000 to 33,000,000l/farm/year); and (c) the country is not an exporter.

Also, it should be noted that Mercosur countries (the free trade agreement encompassing Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) apply a 28% tariff to any dairy product imported from outside the bloc.

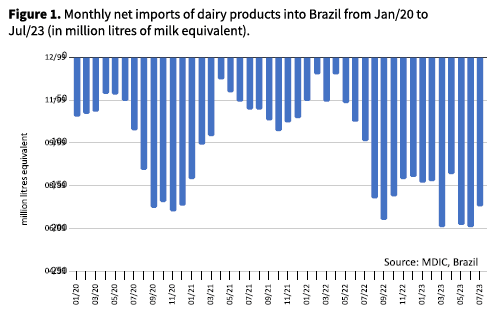

Brazil is largely self-sufficient in dairy supply, usually importing only 1-4% of its demand, nearly all from Argentina or Uruguay. The exceptions are times when BRL/US$ exchange rate favours small exports or when national milk prices are too high as compared to world prices, triggering larger import quantities. The latter is the situation at the time of writing (Fig. 1).

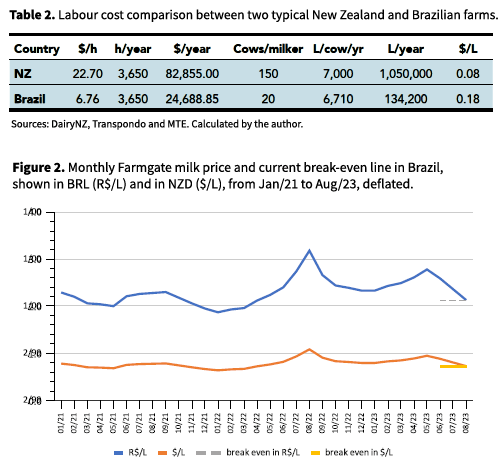

As imports increased, farmgate milk price (which is monthly adjusted) went down from an all-time high in August 2022 ($1.08/L) to $0.72/L last August, reaching the break-even point of most farms (Fig. 2). Because Brazilian milk has only 7.2% milksolids (MS), this would equate to $10/kg MS, a conversion that should be made with caution, as most milk is produced and traded to be consumed as fluid, domestically (3% fat UHT milk is the main product).

Fig. 2. Farmgate milk price and current break-even line in Brazil, shown in BRL (R$/L) and in NZD ($/L), from Jan/21 to Aug/23, deflated.

According to DairyNZ, NZ milk production costs were typically $9.17/kg MS during the 2022/23 season. This means Brazil is producing at a cost roughly 9% higher than the latest NZ cost figures available, on a MS basis (i.e. $9.17 vs $10/kg MS), but 13.9% lower on a volume basis (calculated from $9.17 x 8.9%MS = 0.82/L compared to $0.72/L in Brazil).

So milk purpose (fluid versus solids) and payment system ($/L versus $/kgMS) are very important drivers of competitiveness, within each type of business.

NZ, as an exporter, depends heavily on milksolids. Brazil, largely, does not. Only one Brazilian company (a secondary level co-op) is transitioning from a volume to a milksolids payment, as it depends almost entirely on producing and selling milk powder. All others buy milk by the litre, at most paying a bonus price for percentage MS, depending on their product mix. This co-op’s move will probably stimulate competitors who also depend on milksolids to follow suit (e.g. cheese companies).

Costs and margins

Monthly estimated margin over feed cost is used in Brazil to track trends in profitability. An example is shown in Fig. 3, for the last three years. While the trends are valid for most farmers, actual margins over feed tend to be lower than reported by this type of estimate.

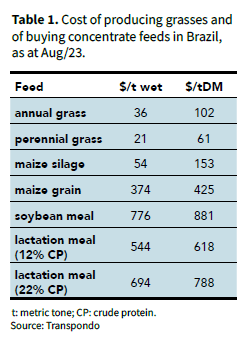

Feed accounts for 45-60% of operating costs in Brazil. The simpler the system, the lower the overhead, so the higher the weight of feed in the cost compound. Table 1 shows recent costs of producing grasses and of buying concentrates in. The grasses and maize silage figures are derived from top farmers. Average farmers have a higher cost.

Table 1. Cost of producing grasses and of buying concentrate feeds in Brazil, as at Aug/23.

What about labour?

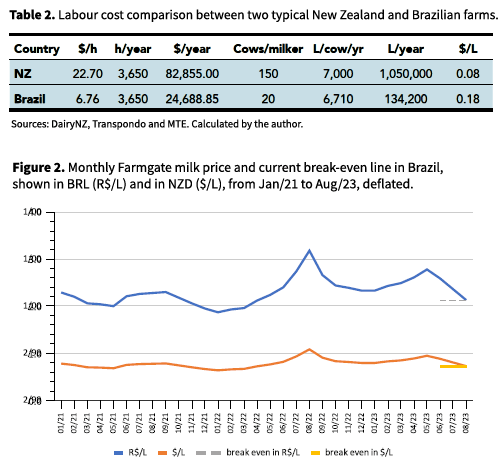

Though it may not look like it, labour is an important component of costs in Brazil. While the value paid for labour on dairy farms ($6.76/hour) may seem extremely cheap to Kiwis, when labour productivity is computed, a completely different picture is revealed (Table 2).

While the milker wage is 70% lower in Brazil, it costs the employer 125% more than its counterpart in NZ by the litre of milk produced. The example considered one labour unit in each country, replaced during breaks and holidays by a person receiving the same wage (Brazilian herds are milked year round, so for the comparison to hold, the Kiwi labour was kept during dry season).

Table 2. Labour cost comparison between two typical New Zealand and Brazilian farms.

Impact of land prices

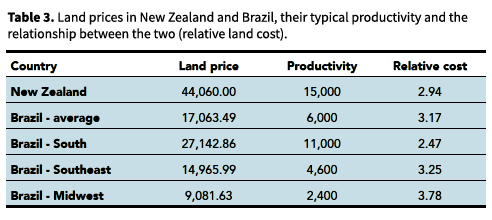

Land is another key factor determining the economic viability of the dairy business. While Brazil’s rural land can be extremely expensive in certain regions, average dairy farm land is 61% cheaper than in NZ. However, productivity is lower than in NZ, which actually makes it cost 7.8% more in Brazil if we divide the price paid per hectare by the litres of milk potentially produced in one year by that hectare (called “relative cost” in Table 3).

Table 3. Land prices in New Zealand and Brazil, their typical productivity and the relationship between the two (relative land cost).

Despite the differences in milk prices and input costs between the two countries, both seem to have a similar estimated proportion of farmers (70-80%) who will be at a loss, should current prices and forecasts hold.

As nearly all milk produced in Brazil is consumed domestically and imports are largely limited to Mercosur milk, the main direct determinants of Brazilian milk price are domestic supply and consumer buying power (currently eroded by inflation).

However, let’s not be mistaken. While NZ depends largely on exports, particularly to China, Brazil too is affected by its trade success, as milk not sold into China competes more fiercely in the world market, lowering prices and making Mercosur milk more attractive to Brazilian importers, thus depressing farmgate prices.

- Wagner Beskow is a senior dairy researcher and farm consultant with Transpondo, Brazil.