Cows in New Zealand are getting a cocktail typically associated with hipsters in New York or London.

Branded Kowbucha, a nod to the popular fermented drink kombucha, it’s being tested by one of the world’s biggest dairy producers, Fonterra Cooperative Group Ltd., to see if it can reduce the amount of methane burped out by the country’s 4.9 million cows.

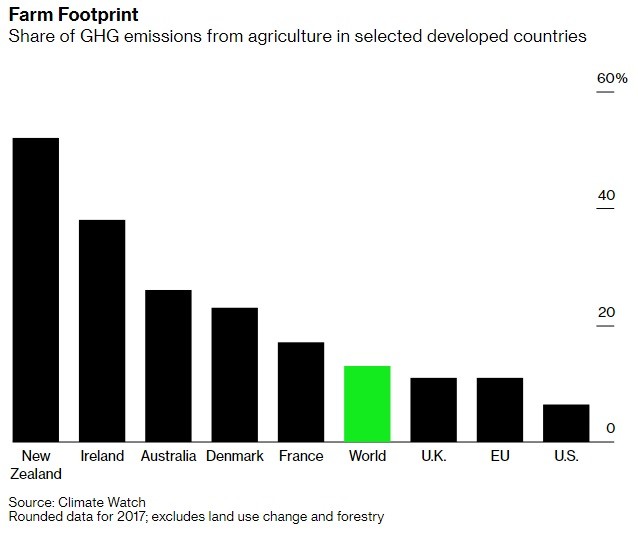

The supplement is the latest effort by the nation’s farmers to solve an increasingly pressing problem of livestock emissions as it pledges to become carbon neutral. Unlike most developed economies, New Zealand is heavily dependent on agriculture, especially cows and sheep, so while others focus on cutting carbon dioxide, it has a much bigger problem with gases produced in animals’ stomachs.

Fonterra has cultures that Kiwi farmers have collected since the 1920s for making cheeses and yoghurts and is now testing which ones can reduce the amount of methane cows burp when they digest grass and feed.

“The fermentations produced by those cultures can have quite dramatic effects on digestion, not just in humans but in animals,” says Jeremy Hill, the co-operative’s chief scientist. Kowbucha is one of the possible candidates for the dairy co-operative, which is also looking at other options including seaweed.

The technology is still at an early stage of research and, like other potential solutions to the bovine problem, faces questions over how to deploy it in the pastures where cows spend most of their days, and whether farmers would be able to afford it. But it’s critical for New Zealand if the country is to reach net zero.

Methane, made of carbon and hydrogen, is up to 56 times more potent than CO2 to global warming when measured over 20 years. The United Nations backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates a global methane reduction of 40% to 45% by 2030 is needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C, as cheaply as possible. Moreover, because methane stays in the atmosphere for only a decade, reducing its output can deliver a relatively quick win compared with CO2, which lingers for centuries.

“If you don’t deal with agriculture, you’re never going to get to these low warming targets,” said Drew Shindell, the lead author on an upcoming United Nations research paper on methane.

The Global Methane Assessment, due to be published next week, shows that curbing human-caused methane emissions by as much as 45% by 2030 will avoid nearly 0.3° C of global warming by the 2040s, preventing more than quarter of a million premature deaths.

But the science behind reducing cows’ digestive gases is a lot harder than curbing other methane emissions, such as from flaring in oil and gas fields or leaks from landfills. Cows and other ruminants use microbes in their stomachs to break down tough fibers that humans can’t digest. Curbing the methane they produce as a result requires tweaking the animals’ biology and physiology.

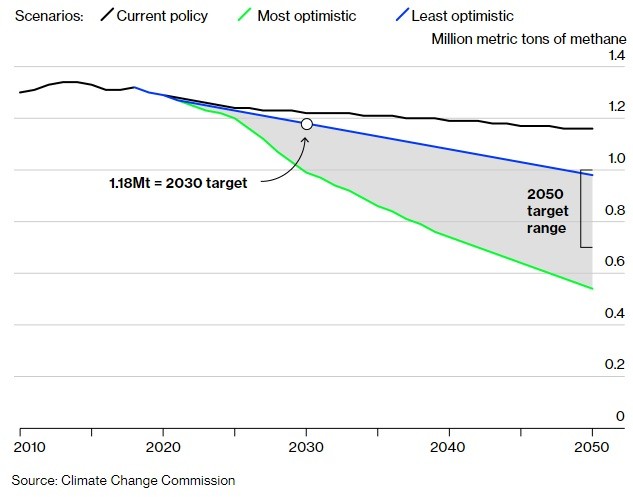

That’s one reason why New Zealand’s farmers aren’t on track to deliver their share in avoiding catastrophic climate change, according to the nation’s independent Climate Change Commission.

Milking It

New Zealand isn’t on track to meet its targets to cut methane emissions

Some of the world’s biggest polluters have pledged to zero out their greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades, including China, South Korea and the European Union. New Zealand is one of the few countries to have a net-zero goal enshrined in law, helping to boost Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s profile among climate activists internationally.

But there’s a loophole in New Zealand’s Zero Carbon Act. The methane that makes up more than 40% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions is exempt. Instead the government set a weaker target to cut methane by between 25% and 47% by 2050 compared with 2017 levels. And the farming industry is exempt from the emissions trading system – the government’s main tool for cutting greenhouse gases.

“It’s a trick. The government carved out biogenic methane,” says Russel Norman, Greenpeace New Zealand executive director and former co-leader of the Green Party.

A true commitment to net-zero would include methane in the overall target, according to Anna Chapman, an analyst at the research group Climate Analytics.

But following through on ambitious climate targets has proven difficult for Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s government in the face of the nation’s powerful agricultural lobby. When she was elected as New Zealand’s youngest female prime minister in 2017, she formed a government with support from the Green Party on campaign promises to make farmers pay for their pollution by bringing the dairy industry into the nation’s decade-old emissions trading system.

Farm Footprint

Share of GHG emissions from agriculture in selected developed countries

Rounded data for 2017; excludes land use change and forestry

It hasn’t happened. With an election looming last year, and the nation even more reliant on agriculture as the pandemic crushed its tourism industry, Ardern struck a deal with the agriculture industry that would further delay its entry into the ETS. Instead, the government has allowed the sector to develop its own ways to measure and price farm emissions. It will check on progress in 2022 and, if insufficient, could bring agriculture into the ETS before 2025. The New Zealand government did not respond to a request for comment.

That threat is putting pressure on suppliers like Fonterra to find a solution. As well as Kowbucha, Fonterra is working with red seaweed on suppressing the microbes. It has a partnership with Dutch nutrition company Royal DSM NV to speed up the deployment of Bovaer, a synthetic feed supplement that’s been shown to reduce methane emissions by about 30%. The company, which has an annual NZ$100 million ($72 million) research budget, has also worked on developing ‘climate-smart’ cows whose stomachs emit less methane, as well as vaccines.

But producing climate-friendly cows takes years, and developing vaccines is “very, very difficult,” says Hill. Seaweed, which has garnered a lot of interest in recent years, is difficult to feed to pasture-raised livestock, who don’t like the taste, and has possible safety issues over substances such as bromoform, a toxic chemical found in small quantities in ocean plants. Even DSM’s promising feed supplement, which has undergone several tests and peer reviews, faces a regulatory wait and questions over affordability.

Yet dairy companies are under growing pressure from consumers to reduce their carbon footprint of livestock, according to Dan Blaustein-Rejto, director of food and agriculture at environmental research organization Breakthrough Institute, who says reducing methane emissions from livestock is critical to decarbonizing agriculture. Making more climate-friendly products may allow them to offer produce at a premium and could help fend off competition from a growing number of alternatives, such as oat milk, vegan burgers and other plant-based alternatives.

If successful, New Zealand’s efforts could become a test case for the global livestock industry, especially nations such as Ireland and Brazil that rely on ruminants for a chunk of export revenue. But the CCC says the technologies being developed can’t be counted on to meet the interim target.

“The silver bullet for dairy production technology has been just over the horizon for the last 12 years” says Harry Clark, commissioner at the CCC. “It’s still yet to arrive.”

— With assistance by Matthew Brockett