Near record high milk prices in Australia are hitting the country’s dairy exporters as Asian food companies ditch local products for cheaper supply from New Zealand and further abroad.

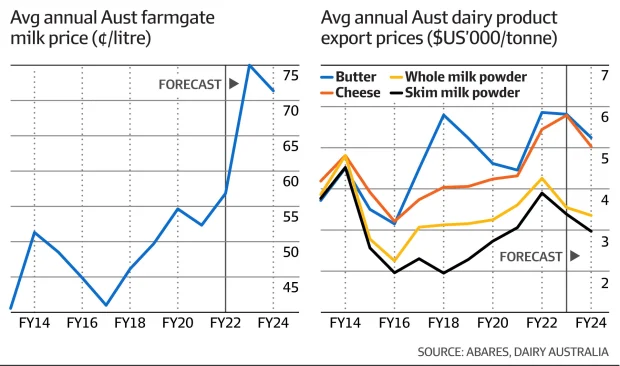

Farmgate prices hit an all-time high of $9.93kg per milk solid in the 2022/23 season, and while they have dipped back to $9.44, they are still 40 per cent above the five-year average. That has pushed supermarket prices higher, with a bottle of milk jumping 13 per cent over the past year which was more than any other food group, according to Dairy Australia.

“Competition for milk within our country has been supporting higher prices being paid to farmers compared with internationally,” said Eliza Redfern, an industry analyst at Dairy Australia. “Milk prices are significantly higher compared to the likes of New Zealand, US and Europe.”

Prices are expected to remain elevated from reduced milk supply and there is risk of further disruption from El Nino, a weather system due to arrive this summer that will likely bring drier conditions and weigh on feed availability.

Last season dairy production in Australia fell a further 5 per cent from flooding, labour shortages and as more farmers left the industry. It also follows two decades of declining supply to just 8.1 billion litres compared with 10 billion litres produced in 2015.

“Competition for milk within our country has been supporting higher prices being paid to farmers compared with internationally,” said Eliza Redfern, an industry analyst at Dairy Australia. “Milk prices are significantly higher compared to the likes of New Zealand, US and Europe.”

Prices are expected to remain elevated from reduced milk supply and there is risk of further disruption from El Nino, a weather system due to arrive this summer that will likely bring drier conditions and weigh on feed availability.

Last season dairy production in Australia fell a further 5 per cent from flooding, labour shortages and as more farmers left the industry. It also follows two decades of declining supply to just 8.1 billion litres compared with 10 billion litres produced in 2015.

While analysts are optimistic about the industry’s supply outlook thanks to ample feed and irrigation, retail prices are expected to remain high for months as dairy processors, which pay the farmgate price for milk before selling it to supermarkets, compete to secure supply.

Rabobank senior analyst Michael Harvey said while he did not expect farmgate prices to climb much higher, the extreme competition among dairy processors would also stop prices falling significantly.

“It’s going to be challenging for processors to be able to compete on milk price, and then get a return from that milk in the global market,” Mr Harvey added.

Australia’s milk prices are significantly higher than other countries thanks to a price setting mechanism that is unique to the country. Under the dairy code of conduct, minimum opening milk prices are set only once a year on June 1, which means dairy processors are not allowed to reduce the prices offered to farmers during the season.

More pain ahead

This compares to New Zealand, where co-operative Group Fonterra twice cut its farmgate milk gate price to $6.65kg per milk solid (MS) for the current season, well below Australia’s average of $9.44kgMS.

Meanwhile, international dairy prices hit their lowest level in nearly five years, according to a major global dairy auction held last month.

This suggests Australian dairy exports are headed for more pain with around 30 per cent of the country’s dairy supply sold offshore. The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (ABARES) forecasts dairy exports to slip 5 per cent to $3.2 billion by mid-2024, after falling 2.3 per last year.

The decline in exports is in part due to China, a key customer, investing heavily in its own dairy industry and sitting on stockpiles of dairy products, particularly milk solids. New Zealand’s The a2 Milk Company has also warned of weak revenue growth and challenges in China’s $28 billion infant milk formula market.

And there are also reports in the industry that companies in Southeast Asia have ditched Australian dairy products for cheaper alternatives in rival markets including New Zealand, US, and Europe where supply has climbed.

ABARES said Australian butter and cheddar cheese, for example, were “substantially higher” than world prices last year, prompting dairy processors from importing countries to consider tweaking their manufacturing specifications to buy cheaper dairy from New Zealand.

Even Australian-based food service buyers are sourcing cheaper products overseas, particularly from New Zealand. Domestic milk imports jumped 17 per cent last season, according to Dairy Australia, with half of Australian milk imports coming from across the Tasman.

“China has been buying a lot less milk, particularly powder and that is the biggest trade flow,” said Rabobank’s Mr Harvey. “[Australian] farmgate prices have held up and not fallen as much as the international commodity milk complex” which while bad for exporters was a “good result for farmers”.

Even so, some farmers are still worried.

Still nervous

Phil Ryan, who runs a dairy farm in NSW’s Bega region and supplies milk to Bega Cheese, said he was disappointed by this year’s slightly lower farm-gate prices, and was concerned about the future.

“I am very nervous. Looking at international trade prices and price announcements in New Zealand, it is quite clear that farm-gate prices will be under a great deal of pressure next year,” he said.

While he is hopeful the country’s declining supply of milk and strong demand from Australian consumers will offset the trend, he’s also aware price pressure could accelerate the exodus of farmers. Nearly one-third of farmers have left the dairy industry in the past decade.

Mr Ryan, who has 170 Holstein and Jersey milk cows, is also among the thousands of Australian farmers feeling the pressure from higher inflation and labour shortages.

“We are heavily reliant on workers, and it’s quite hard to find them in rural and regional Australia,” he said, adding backpackers had not returned to pre-COVID levels and workers were reluctant to move to rural areas because of a housing shortage.

The farmer added that Australian dairy processors needed to expand into high-value products such as premium cheese nutritional products and infant formula rather than bulk products like milk powder.

But ABARES predicted the profitability margins of dairy processors will fall and discourage investment in milk facilities.