Luke Micallef and his wife Jess run their family farm, Camden Valley Veal, where all the meat they produce comes from animals that are traditionally considered waste products in the dairy industry.

The family downsized from a large production dairy farm as they were uncomfortable with the practice of destroying bobby calves, the removal of bull calves from their mothers to slaughter.

They now run a milking herd of just 25 jersey cows in Cawdor, on the outskirts of Sydney, selling the aged meat and veal direct to butchers.

“We rear all our own bull calves and buy bull calves in from all the local dairy farms, and we rear them through until they get to about 220 kilograms,” he said.

Pressure to reform welfare in dairy farming

The dairy industry is under pressure to improve its reputation on the issue of unwanted calves.

In a Nuffield Scholars report, Dr Sarah Bolton has written that dairies are missing out on a high value niche market for veal, among welfare conscious consumers.

“There is a very real monetary value attached to a social licence to operate,” Dr Bolton said.

“The general population is beginning to put more emphasis on making more ethical food choices.”

Dr Bolton also notes in her report that globally, dairy beef is rather common.

She found that in Europe, surplus calves and cull cows contributed up to 80 per cent of the beef consumed, while it was the opposite in Australia.

But she found that due to food trends and a focus on healthy eating, people wanted to learn more about what they consumed.

“People want to reconnect, and I think there is a real opportunity in that for agriculture,” she said.

At Camden Valley Veal, Mr Micallef is on board, producing both veal and aged beef with a focus on the wellbeing of his animals.

“It’s quite different to what people might consider traditional veal, in that the calves are all grown outside on fresh milk, they’ve got a complete diet of pellets, pasture and hay,” he said.

He said that contrasts with consumer perceptions that dairy veal was a young, week old calf, “deprived of movement and deprived of things like iron … to enhance the colour of the meat”.

Overcoming challenges

The Micallefs approached many butchers who would not even trial their veal, but their persistence paid off.

“Some [butchers] would start off with a calf a month and it’s just grown and grown for us,” Mr Micallef said.

He said the dairy industry is unfairly stigmatised, because the lamb and pork industries both process young milk-feeding animals.

Mr Micallef said Australians have not developed a culture for eating veal.

“We need the consumer to accept and embrace dairy beef and veal, so that we can continue to give these calves a better life,” he said.

This challenge is not surprising, as 83 per cent of Australians have a distant or non-existent connection to agriculture, according to a 2017 National Farmers Federation survey.

Protests condemning meat production are also on the rise, with dozens of high-profile demonstrations taking place in Australia over the past two years.

Mr Micallef said the protests have their place in an evolving society, but disagreed with the untrue smear campaigns that some organisations run.

“[But] poor management and poor handling of cattle — I’ve got absolutely no problem with those things being exposed because they shouldn’t happen,” he said.

“People see things that they’re not comfortable with and assume that it’s industry practice when it’s not.”

Preserving public trust

Mr Micallef said it is important people understand where their food comes from to ensure that Australian meat production and consumption remain viable.

“We also do dairy education in schools, so we take cows around to schools and show kids where milk comes from and how different dairy products are made,” he said.

He said he found ignorance about farming in regional areas, as well the cities.

“Earlier this year we did a week trip out to Dubbo and visited schools out there and I was amazed … that there were six-year-olds who had never seen a cow before,” Mr Micallef said.

“And the sad thing is that often kids have a better understanding of where food comes from, than their parents.”

Future of farming

Mr Micallef believed most farmers want to change the current practice, but they needed more incentives.

“I don’t think an industry can sit by and have half of its [animal] population considered a waste product and expect to remain viable,” he said.

“I think if we’re going to bring these calves into the world, we’ve gotta have a use for them.”

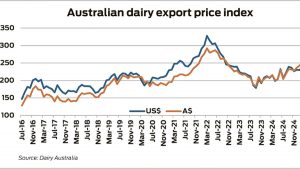

Against a backdrop of drought and stagnating milk prices, the Micallefs’ move into dairy beef, had given the family hope.

“As the industry’s gone through more and more struggles over the last ten years, people are looking for new ways of doing things in a way that they can keep businesses viable,” he said.

“Some people are going to cheeses, some people are bottling their own milk.

“For us, we saw a niche and need for the use of the bull calves.”