The world’s dairy farmers are facing an existential crisis.

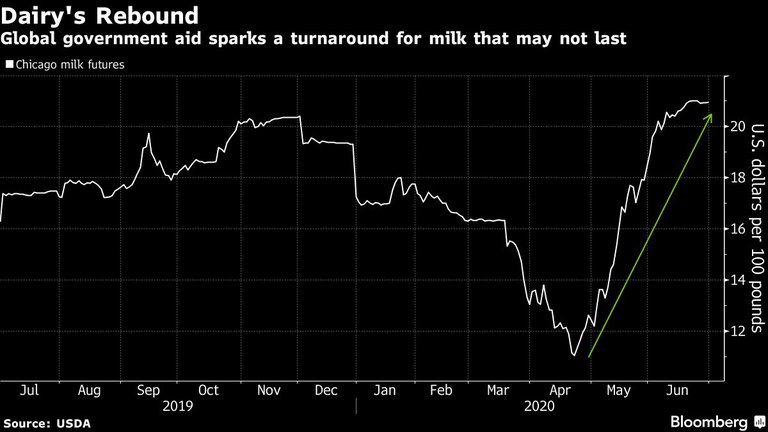

They’ve dumped millions of gallons of milk, slowed output and sold off older cows. Global governments stepped in with stimulus cash that provided some much-needed temporary relief, helping benchmark Chicago milk futures to almost double in two months. But once the aid money starts to dry up, many producers will confront tough choices again: suffer through losses, or pack it all in and shut the farm.

It’s going to be a long time before restaurants go back to serving buttery, cheesy dishes on the scale they did in the pre-pandemic world. While lockdown restrictions are easing, slower economic growth means consumers will be cutting back on dining out and even home-delivery orders.

That’s a hit the dairy industry won’t be able to sustain. Even with billions in stimulus, the contraction for U.S. herds will likely match record levels this year, according to the National Milk Producers Federation. Declines are also expected in Europe and Australia, two other regions key to global exports.

“Are people still at home in three to six months, ordering pizza to watch a football game? Or are they conserving their money, and will they stop ordering out?” said Matt Gould, editor at Dairy & Food Market Analyst Inc. “At no point have we seen the light at the end of the tunnel, and even now with prices spiking, we could be in the ditch in three to six months.”

Dairy is one of the world’s most important food markets. The sector accounts for about 14% of global agricultural trade and more than 150 million farmers keep at least one milk animal, according to the United Nations. The industry is valued at about $700 billion, but it’s facing a reckoning. For years, milk demand has been on the decline in developed countries. That’s only accelerated recently as more consumers turned to plant alternatives amid climate concerns.

When coronavirus lockdowns went into place, dairy markets were among the hardest hit in the food world. It turns out, consumers the world over eat a lot more cheese and butter when they’re dining out than they do at home. As restaurants shuttered, farmers were left with an overwhelming glut. Hundreds of millions of pounds of milk got dumped.

Things still looked relatively dismal until governments stepped in to intervene. The U.S. promised $2.9 billion in its dairy bailout. The European Union pledged 30 million euros ($34 million), and Australia has also earmarked funds for the industry. That sent milk futures in Chicago soaring after touching a decade low in April.

Wisconsin farmer and dairy consultant Daniel Olson is betting on retrenchment.

Many producers are likely pulling in more profits now than they were pre-pandemic, Olson said, but he’s doing everything he can to lock in prices, with futures still trading near $21 for 100 pounds, the highest since 2014.

“It’s just a matter of time before it goes down to as low as $10,” Olson said. “I’m using this opportunity to never see $10 on our farm.”

The recent price rebound and the government aid will allow some producers to get through this rough period, but it won’t be enough to forestall the long-term trend toward bankruptcy and farmers leaving the industry, said Peter Vitaliano, the chief economist at the National Milk Producers Federation, whose members produce more than two-thirds of U.S. milk.

In 2019, there was a 9% drop in licensed U.S. dairy herds, a record high, Vitaliano said.

“I expect there will be a similar shake-out this year,” he said.

That’s likely to be the case globally, as well. The European Commission has forecast the region’s dairy herd could drop by about 0.7% this year, after a 1.2% decline in 2019. Almost 500 Australian dairy farmers left the industry in 2019, and the trend will probably continue as production costs have stayed above retail prices.

‘Heavy Inventories’

Even with herd contraction, the world will see overflowing supplies, according to analysts at Rabobank, which forecasts a 1% increase in production in the second half of 2020 from a year earlier in the major producing regions.

“Heavy inventories and reduced demand growth will weigh on global milk prices through 2020 and into 2021,” the analysts led by Ben Laine said in a June report.

Still, there’s the chance that governments could supply more stimulus. The Rabobank analysts say that’s a possibility in the U.S. ahead of the November presidential election. Donald Trump has counted on farmers as a key part of his constituency.

But without another injection of funds, there’s more pain in store for farmers.

Tony Sarsam, the chief executive officer for bankrupt Borden Dairy Co., expects more people to continue to eat at home — especially as the pandemic leads into a recession — which could worsen dairy demand. Plus, there’s the longer-term problem of consumers turning away from drinking milk.

“How fresh fluid milk becomes a staple again remains to be seen,” he said. “It’s not going to be solved with a government program. Consumers want new ideas, indulgent foods, healthy choices and convenience — and the dairy industry has a lot of work to do there.”

— With assistance by Ainslie Chandler