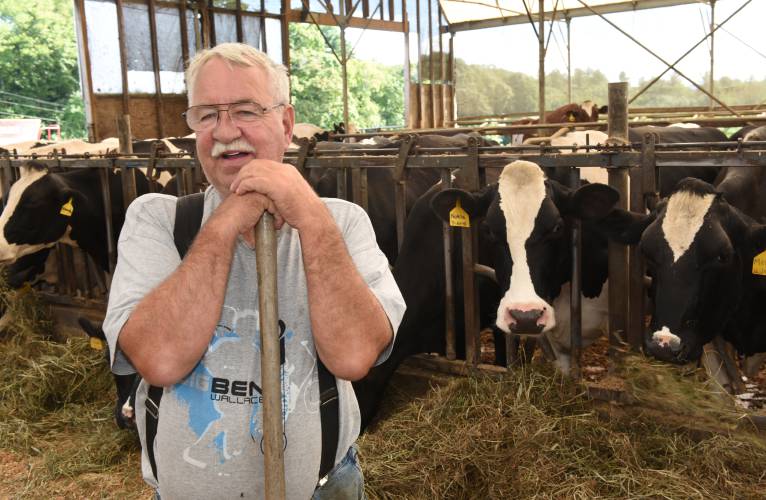

“Dairy farming is not easy,” Duprey said. “You put in a lot, but you don’t get back anywhere near as much, except satisfaction.”

Duprey is a third-generation dairy farmer. He lives in the house and on the land where his grandparents lived and farmed, and then, his parents. His son helps on the farm, when he’s not working his full-time job. His two daughters live near Boston and have careers there.

Sunbrite Farm at 144 Eden Trail in Bernardston was passed down to Duprey after his father died. Today, Duprey owns about 100 acres — 70 are woodland and 30 are pasture and hay. To keep the cows fed, they also rent another 75 acres for haymaking.

“He died when I was a kid,” Duprey said of his father. “He started farming after he was in the service. I watched him work hard, and I helped. But I never knew just how hard it was until I took over.”

Duprey’s father died from a brain tumor. He said he was only 12 years old at the time, so his mother rented the land to farmers, though that never lasted long.

“It sat idle for a long time,” he said.

When Duprey graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, he decided he wanted to try dairy farming on his own.

“I didn’t know what else to do,” he said.

Cost of living

Duprey, like many other dairy farmers in Franklin County and across the state, said dairy farming has always kept a roof over his and his family’s heads, but not much else. His wife, Deborah Barton-Duprey, 64, has always had to work a full-time job off of the farm to keep food on the table and for the health insurance.

“We raised three kids,” he said. “We couldn’t have done it without her working off of the farm.”

Barton-Duprey said though she has always worked off the farm, she has also helped on the farm when she could. For instance, she helps her husband and son get the cows ready for milking.

Selling milk, the couple gets a paycheck every two weeks for their efforts. They have 120 cows and are milking about half of those (56). Forty are young stock, so they’ll be milked in another year or two.

Duprey said what they get paid for the milk doesn’t cover the cost of living, even for just the two of them now that their three children are grown.

“You do this because you love it,” he said.

Duprey said he receives around $18 for 100 pounds (11.6 gallons) of milk. That’s the price at this time, though he said it fluctuates from day to day — sometimes a little more, sometimes a little less.

He, his wife and son, plus the three part-timers who work for him milking every morning and every evening, produce about 3,800 a day. A single cow can produce up to 65 to 70 pounds each day.

“The amount they produce can change each day, too,” he said. “A heat wave can knock down production. So can other things.”

‘We’ll keep doing what we’re doing’

Duprey said it’s almost impossible for someone to start dairy farming at this point, because of all of the costs and little return financially.

“It’s a lot of manual labor and you’re always looking for ways to make things more labor-efficient,” he said. “You need machines that help lighten the load. You need a milking parlor. Unless you have a lot of money to begin with, you’re not going to get rich doing it, so not a lot of young people are looking at it as an option.”

When he first started dairy farming, it was extremely labor-intensive, so there was a much higher turnover of employees. He said dairy farmers have struggled with that for years.

Duprey said a state incentive program has helped him buy equipment and invest in the farm over the years.

“I’m not sure what we would have done without the program” he said. “It was getting to the point of ‘I have to fix these things or quit,’ when the program assisted with some money to fix them.”

He has used the program twice in 10 years to borrow money that he could pay back slowly and at a good rate.

Barton-Duprey, who does the bookkeeping for the business, along with working a full-full time job off the farm, said she loves the farm, too. It has taught her to be frugal, and she knows how much her husband loves what he does, so that makes it all worth it.

“I grew up in Leyden,” she said. “I always worked two jobs when I was old enough, so I could pay my bills and buy whatever I wanted. The way you live on a dairy farm put stress on the marriage in early years, because I couldn’t do that any longer. But I learned you don’t do something like this for the money.”

Duprey said he’ll see how things go. He said he has no intention of retiring at this point, but you never know.

“We’ll keep doing what we’re doing,” he said. “We’ll keep equipment purchases to the bare minimum and spend time taking care of the cows because, after all, they pay the bills.”

Duprey said the only advice he can give someone who is either thinking about starting a dairy farm or taking one over is to not think they have to get really big really fast and to realize you need an outside income to keep it going.

He worries about the future of dairy farming. He’s not sure any of his children will end up taking over his farm, and he said it’s the same with many other dairy farmers he knows.

Family tradition

According to Claire Morenon, communications manager at Community Involved in Sustaining Agriculture in South Deerfield, land costs are high in Western Massachusetts and dairy farmers do not get paid well, so it makes it difficult to survive financially.

Currently, there are 29 (bovine only) dairy farms in Franklin County. There are 142 across the state, with half of those in Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden counties. She said dairy farms make up about 2 percent of all farms in Massachusetts and 3 percent of the farms in the Pioneer Valley, while they make up 18 percent of agricultural activity. Twenty percent of the milk in the state is produced by Massachusetts dairy farms.

“Dairy farmers are anchor tenants,” she said. “They manage a lot of land and livestock, but get little for what they do. They still have all of the costs other farmers have, like equipment maintenance. So, many of them are closing their doors.”

Morenon said it’s an emotional issue for farmers, because they take what they do seriously, love it so much and many have done it for as long as they can remember, so deciding to stop can be quite traumatic, especially if generations before them were dairy farmers, as well.

“It’s a family tradition for most dairy farmers,” she said. “Not many, if any, new farmers will choose dairy.”

Morenon said the process of producing and selling milk is efficient. Farmers milk the cows — some are turning to robotics to make it even more efficient — and trucks pick it up at the farm and get it to nearby plants, like Cabot and Hood. There is at least a “splash” of Massachusetts milk, and in many cases it’s local, in the milk people drink in Franklin County. Milk is collected from all over the state and combined.

“It’s a well-functioning infrastructure,” Morenon said. “But, there are big, regional meetings that are happening to discuss how dairy farmers can stay in business. Farmers are always thinking about how they can maintain the status quo and make it even better. The industry needs to be stabilized. They’re just not making enough money to survive.”

Morenon said many dairy farmers have started to diversify, so they have other sources of income to fall back on, like ice cream stands and crops they never grew before.

“They’re just not on stable ground and that’s sad,” she said. “They’re just not as visible as other types of farmers because they don’t sell their products directly to the public; so, for instance, you don’t see them at farmers markets selling milk.”

The challenge, Morenon said, will be helping farmers find a way to make it possible to pass their farms on to the next generation and keep the industry viable.

Duprey said he hopes that’s possible.

“We’ll see how it goes over the next few years,” he said. “I’d like to keep doing it a few more years, at least. It all depends on how I feel. Then, we’ll see what happens after I decide to retire.”