This compares with more than 50 conversions in the region during some of the peak dairy boom years.

Environment Canterbury said that its consent figures showed that there had been a steady decline in dairy conversions in the region since 2013. This was despite the completion of the massive Central Plains Water irrigation scheme last spring which some feared would lead to another surge in conversions.

ECan senior manager service delivery Nick Daniels said the regional council had “introduced some of the strictest rules in the country to help halt water quality deterioration and deliver the improvements the community demands”.

This includes requiring all farmers to operate within strict limits and adhere to industry agreed good management practice guidelines.”

Rather than managing intensification of farming activities by capping cow numbers or managing herd sizes, ECan instead imposed nutrient loss limits that allowed farmers to manage their activities within these limits.

The rules, introduced via the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan, became partly operative from 2015 and included stringent rules in areas with rising nitrate levels. In the Selwyn-Te Waihora catchment, much of which flows into Lake Waihora/Ellesmere, nitrogen losses from dairy farms must be reduced to 30 per cent below their average 2009-2013 nitrogen losses by 2022.

These controls, in place to protect waterways from intensive land practices, mean that stocking levels were effectively capped for most dairy farmers in Canterbury, Daniels said.

Federated Farmers North Canterbury provincial president Cameron Henderson said a combination of nutrient limits, flat payout prices, fewer buyers for dairy farms and more cautious bank lending had led to a waning interest in dairy expansion and conversions.

“It is hard to make the figures work, considering the cost of converting and accessing water for irrigation.

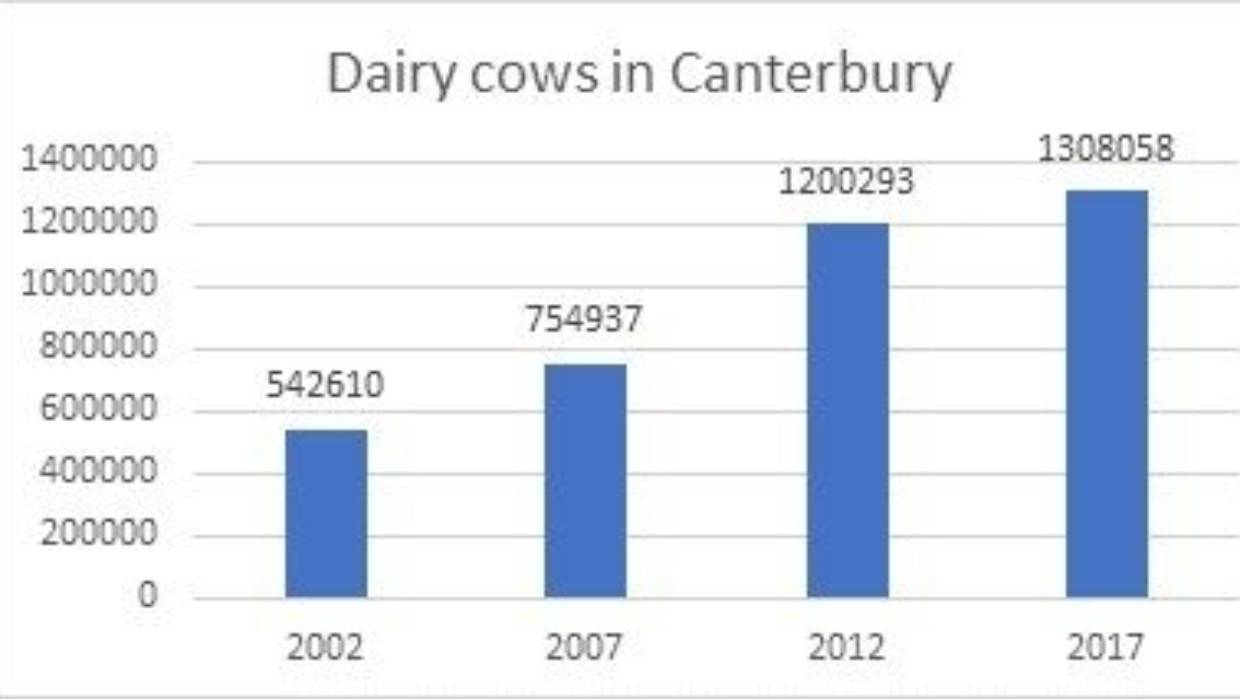

Canterbury farms the biggest and highest-producing herds in New Zealand, with numbers soaring to 1.3 million dairy cows and young replacement stock in the region in 2017, compared with 542,610 in 2002.

“This is happening, not just in Canterbury, but other regions that don’t have as stringent nutrient limits.

“There is not the gold rush on dairying there used to be and cow numbers are becoming naturally limited.

“As a dairy farmer it is nice to have the industry slow down and consolidate.”

Henderson, who farms at Oxford, said that when he converted in 2011, 60 dairy sheds were built in Canterbury that year.

“There has been a big mood change in the last eight years. Previously the attitude was that if you had land and water you put it into dairy and you couldn’t go wrong.

“People are now more aware of the risks and benefits, rather than thinking you will make money regardless.” Henderson said.

Canterbury farms the biggest and highest-producing herds in New Zealand, with numbers soaring to 1.3 million dairy cows and young replacement stock in the region in 2017, compared with 542,610 in 2002.

The region farmed 19 per cent of the national dairy herd in the 2017-18 season, producing 21 per cent of national milksolids production. This makes up almost half of the South Island dairy production, which at 44 per cent of the national milk supply threatens to eventually overtake the North Island’s dairy farming dominance.

ECan said that in 2018, the number of dairy effluent consents granted equated to 10 farms being converted from another farming land use. This was small compared to the 1333 farms with a dairy effluent consent in Canterbury. An additional 27 farms applied for an increase in dairy herd size.

Of these, seven of the conversions and 22 of the herd size increases were on farms within irrigation schemes, or collectives where nutrient loads were distributed amongst farmers, but cannot exceed the overall nitrogen load allocated to the scheme.

Daniels said that farms looking to convert from another land use can only do so within the farm’s existing nutrient leaching limit, which makes dairy conversions increasingly difficult to do. A farm previously used for sheep farming, for example, would need to make significant environmental enhancements to ensure that the increased nutrient load from dairying was offset.

In the Mackenzie Basin, there have been no new dairy conversions since 2014-15, when the controversial high country station Simon’s Pass was consented for large-scale dairying.