Future five: the key areas to watch for the future

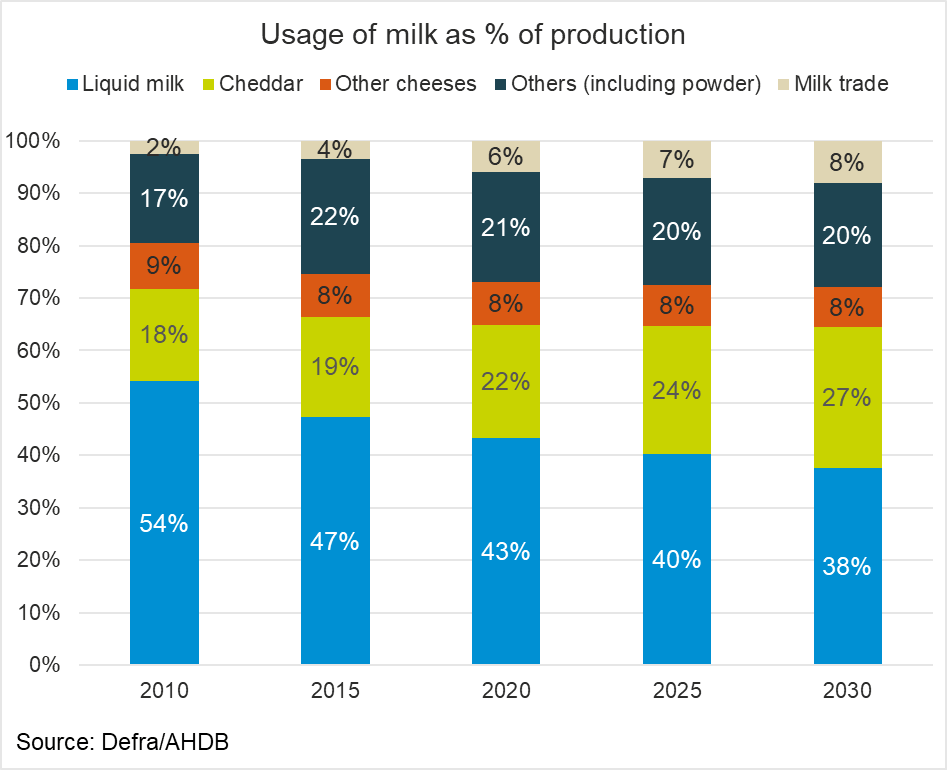

-Rise in proportion of milk used in manufactured products

-Resultant increase in value of milk solids

-Continual risk of business disruption

-Need for flexibility, resilience and adaptability

-Risk to efficiency levels to deliver that adaptability

In January, when we penned our article looking ahead to 2020, coronavirus was predominantly an issue for those trading with China. How the world has changed in the last six months.

Global trade

The FAO is forecasting a contraction of 4% in world exports in 2020 due to coronavirus, with faltering import demand – the sharpest year-on-year decline in three decades.

Widespread disruption caused by the pandemic has hit trade, although, apart from some initial short-term challenges, dairy markets have been relatively resilient, on the whole. However, across the globe, the FAO is expecting a widespread economic slowdown. Lower petroleum prices will have a significant impact on oil-rich countries and their ability to afford imported dairy products.

On top of that, Brexit is now a certainty, although we still do not know what the final trade relationship will look like. Exchange rate risk and general trade disruption remain a concern and the uncertainty is likely to make the whole supply chain more risk-adverse.

However, concerns about trading post-Brexit are mirroring some of the early coronavirus questions around ensuring shelves were full during lockdown:

-How complex is the supply chain?

-How reliant are we on imports for finished products or key ingredients?

-How reliant are we on specific export markets, and how easily and quickly could we switch to alternative markets?

The continual unrest in global trading is making it clear that the companies that will thrive are those that are astute enough to spot the opportunities and have the agility and flexibility to benefit from them. However, what is possibly more important is that companies respond quickly to challenges, whatever they may be, and have the resilience to survive them.

Consumption trends

Over the last few months, in general, consumers moved from being cash-rich/time-poor to being cash-poor/time-rich. The resultant increase in home baking probably isn’t sustainable for everyone as lockdown is eased. The return to work and increase in travelling will make many people time-constrained once again. An increase in home working may allow some the luxury of holding onto lockdown habits. For others, unemployment will put pressure on household finances and mean shopping will be restricted to necessities.

Some habits may continue for longer. The move to online shopping, for example, is likely to be a timesaver few will want to give up. However, selling groceries to consumers online brings different dynamics and challenges. For example, how do you launch a new product when on-shelf advertising and gondola ends are not visible and consumers just add their long-established favourites into a virtual shopping cart?

One of the key long-term trends that we’ve seen is how consumers have shifted the way they consume dairy. While overall dairy consumption continues to increase, consumption per capita is showing a movement away from liquid milk and towards manufactured products like cheese. Consumption per capita of cheese will reach a natural saturation point at some stage, although there are no signs of that yet. However, with population growth, changes in domestic consumption and further increases in exports, we see a clear rise in the relative value of the solids element of milk.

What does that mean for UK dairy over the next 10 years?

-Increase in exports and domestic consumption of cheese, so that by 2030 around 27% of UK milk will end up in Cheddar

-UK milk production needing to increase to meet shifting demand, potentially from 15bn to 16bn litres per year by 2030

-Gradual reduction in the proportion of milk consumed domestically in liquid form

Rather than the historic 50:50 split, in five years’ time, 60% of milk in the country could be destined for manufactured products and only 40% for the liquid market. This has implications for how we pay for the milk, with a higher requirement for milk solids than we have seen historically.

Environment and sustainability

The start of 2020 has reconfirmed concerns of extreme weather, and such events are likely to become more frequent and continue to impact production. That raises key questions around exposure and risk:

-Have you carried out a risk assessment for extreme weather, be that drought or flood?

-Are there measures you can take to mitigate the risk?

-What have you learnt from previous weather issues; what worked and what didn’t?

We should stop treating extreme weather events as a surprise and risk-assess businesses to understand which events have the potential to cause the most disruption. For example, if periods of flood, followed by drought are to become the new norm, what water management do we need to build resilience?

At the same time, environmental concerns are increasingly driving consumer decisions around food choices. UK farm support is changing and will increasingly be guided by a philosophy of ‘public money for public goods’. Although in the short term the overall level of support available could be the same, the amount of money distributed will also depend on environmental scheme design and uptake.

Changes will need to be made to food supply chains to meet the Government’s pledge to be net zero by 2050, and we can expect to see both political and consumer pressure on food producers to help the country meet this challenge.

Understanding on-farm costs of production and marginal returns will never have been more important. If livestock farms are going to be paid to produce environmental products, how much will this be in addition to, or at the expense of, agricultural output?

Flexibility versus efficiency

The challenges of 2020 have already put a focus on the flexibility and resilience of companies and individuals across the supply chain. However, as the dust starts to settle, there are some fundamental business questions that are worth consideration:

-Length and complexity of supply chains

-Reliance on one product type or one route to market

-Level of spare capacity and ability to cope with increases in demand

-Flexibility in production, level of automation and ability to cope with a reduction in staff numbers or need for social distancing. Automation may seem like the answer but may simply lead to an increased need for technical and engineering support

-Reliance on individuals, and the need for staff flexibility. Can staff cover other jobs and is the level of specialists versus generalists right?

-Stock levels of finished products, key ingredients or packaging

All of these are simply raising the efficiency-versus-flexibility question. For years, companies have been forced down the drive for efficiency in order to compete. However, when rapid changes occur because of lost sales channels, restrictions due to social distancing or increased staff sickness, this changes the relative level of risk. So will we see companies build flexibility and buffers into the process rather than simply driving for efficiency?

The lack of cash across the supply chain is going to limit reinvestment. With pension pots depleted, those who still have the legacy of final-salary pension schemes to shore up may see an increased demand for money to be diverted into doing just that. However, where there is a lack of cash, there is also an increased opportunity for mergers and acquisitions. The current uncertainty could drive an increased rate of consolidation in the industry, assuming competition laws allow.

Conclusion

With Brexit, the UK supply chain will need to reassess its view of demand from consumers, both domestically and internationally. The UK market has long been characterised by an overt focus on liquid milk and retail customers. The reality is that if we want to take advantage of emerging opportunities, we need to think more broadly, in terms of international reach and product portfolios.

While we still don’t know what the playing field for trade looks like in the post-Brexit environment, we do know that global demand continues to increase. Population and income per capita growth will continue to act as key drivers. So how do we compete? While we may not be the cheapest commodity producers, we certainly know how to produce world-class dairy products, and I can see a drive for more added-value foods using the provenance that GB has.

This may require an adjustment in milk utilisation to ensure that we are producing the right products for the right consumers. As the proportion of milk used for manufactured products increases compared with the liquid market, the importance of milk solids will become ever more evident.

As if the factors above weren’t enough, we also have the Government’s consultation on contracts now underway. While the debate could well be heated, we mustn’t lose sight of the macro-economic factors that are playing out around us. The future is likely to bring greater exposure to world markets and, with that, increased uncertainty and price volatility. Risk management will become even more important, both in terms of the outright price of inputs and outputs but also market exposure for those outputs.

Coronavirus has shown us that things can change dramatically in unexpected ways. It will be our ability to respond to the inevitable challenges that will determine the extent we can take advantage of that demand. In my mind, working as a joined-up supply chain has never been more important than it is now, in order to provide the flexibility we need to thrive in this ever-changing world.