Consumers are still standing in the grocery checkout line with more dairy in their cart than in the past, but the industry can’t replace the lost food-service demand and the throttled exports by selling each grocery customer an extra gallon of milk, a little more butter for their home-baked goods, and a small package or two of cheese.

The dairy-industry supply chain is in shambles. No one issue is entirely to blame, but the combination of lost sales to food service, logistical snarls and full warehouses has forced some processors to take on less milk or to idle completely. On the East Coast where the pandemic is most severe, some processors can’t run at full speed because their employees are staying home for fear of contagion. While many balancing plants are running as hard as they can, there’s simply too much milk and too much cream. As the spring flush accelerates, the industry is buckling under the strain. Hundreds of loads of milk are going down the drain or into a lagoon every day.

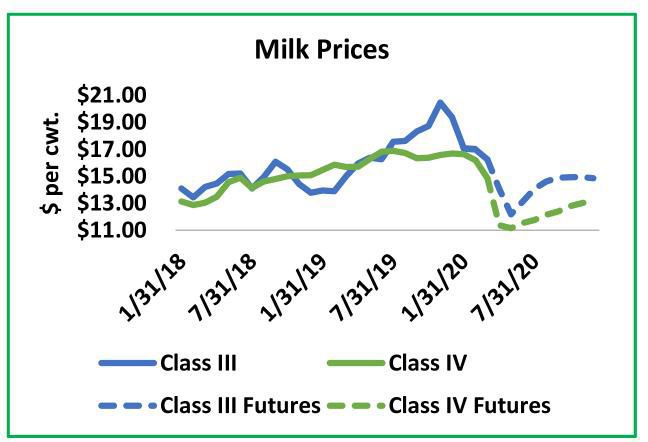

Dumped milk means many producers will suffer steep discounts on already inadequate milk checks. The impact of the novel coronavirus has been heartbreaking for the dairy industry, which must quickly move fresh products to market. Since Jan. 31, Class III futures have lost between 15 percent and 30 percent. May Class III futures are more than $5 per hundredweight less than they were two months ago. Class IV contracts have lost one-third of their value, with May through July contracts reduced by more than $6.

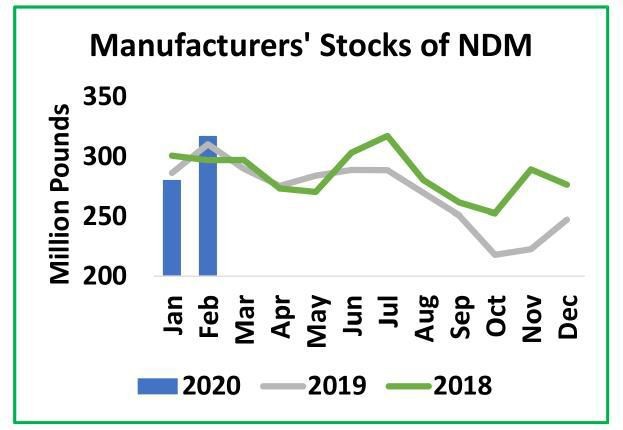

Among agricultural commodities, Class IV futures have sustained some of the steepest losses. Both nonfat-dry milk and butter are struggling with oversupply. This past week Chicago Mercantile Exchange spot nonfat-dry milk decreased 5.75 cents to 86.25 cents per pound. Milk powder depends on foreign demand, and the strong dollar and logistical woes already slowed exports in February. After adjusting for Leap Day, U.S. nonfat-dry-milk exports slumped to 4.7 percent less than year-ago levels. With product sitting in warehouses, manufacturer inventories reached 317.5 million pounds Feb. 29, the largest amount since December 2017. Exports have slowed considerably since February; output has not.

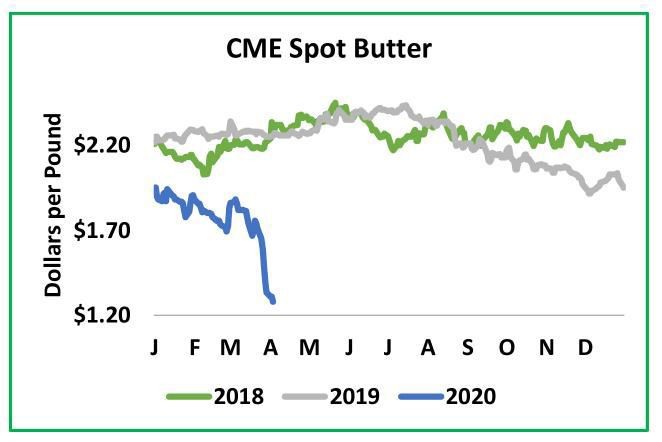

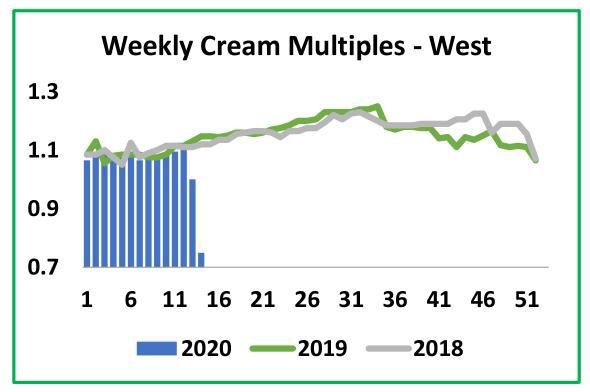

Butter has been abundant for some time, but recently the situation has worsened. February butter output was 5.2 percent greater than the prior year, after adjusting for Leap Day. Since then butter production has likely increased even more. The sharp increase in fluid-milk bottling has spun off more cream. Meanwhile steep declines in restaurant traffic have almost halted the flow through food-service channels of processed cheese, butter, cream, sour cream, ice cream and other products laden with milkfat. Cream is now historically cheap. In mid-March cream traded in the West at or 1.2 times the butter price. This past week multiples ranged from 0.5 to one. Butter makers are likely filling their churns, but there’s still cream pouring down the drain. This past week CME spot butter decreased to its cheapest price in a decade, at $1.28, a decrease of 20.75 cents from the previous Friday.

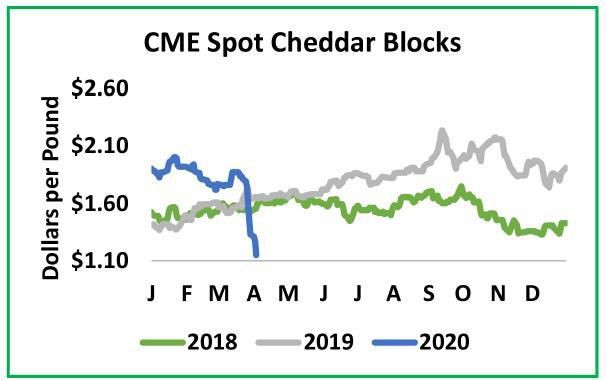

The cheese markets also revisited their 2009 worst prices. CME spot Cheddar blocks decreased 44 cents to $1.15. Barrels decreased 20.25 cents to $1.1375. U.S. cheese production reached 1.03 billion pounds in February, an increase of just 0.1 percent from a year ago, after adjusting for Leap Day. But Cheddar production was 3.7 percent greater than the prior year, implying there’s a lot of cheese that may arrive in Chicago if it can’t find a retail outlet. U.S. cheese exports to Mexico reached the greatest-ever total for the month of February, but sales to South Korea and Japan decreased by nearly one-third year-over-year. COVID-19 took hold in Southeast Asia before it did in Mexico, so that trade pattern doesn’t bode well for U.S. cheese exports in the months to come.

The red ink and dumped milk make it clear that without a thriving food-service sector and little outlet for exports, U.S. milk output is far greater than demand. Unfortunately severe contraction will be necessary to bring milk production in line with consumption. The markets are clearly telling dairy producers to cut output, and many cooperatives echo that message with programs to penalize overproduction. Ideally dairy producers would send more cows to slaughter and at least recoup a beef check. But the packing industry is running into its own processing-capacity issues. Slaughterhouse employees must often work in close quarters. The meat industry is finding it difficult to accommodate social distancing; kill volumes could slow due to staffing shortages. If the issue worsens, it’s possible dairy producers may not be able to cull as quickly as the market demands.

Grain Markets

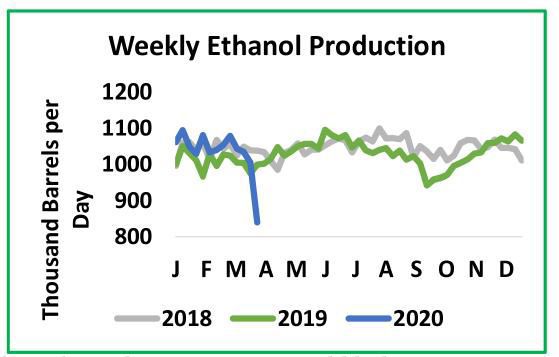

Ethanol plants are slowing output or closing their doors altogether, disrupting feed markets throughout the Corn Belt. The corn basis had been sky-high since the rains became problematic this past spring, but now the basis is close to zero in much of the Corn Belt. Cash corn values have decreased greatly. Dairy producers and other livestock growers who fed distillers grains will need to adjust their rations, which likely means more soybean-meal purchases. Unfortunately soybean meal is one of the few commodities that has been increasing in value.

The soy complex had some further support this past week from fears that Argentina would halt exports. Port workers are demanding closures so they can stay home until the virus recedes. But Argentina depends on export taxes and is likely to try to keep product moving, albeit at a slower pace.

May soybeans closed at $8.815 this past Friday, almost 20 cents more than the previous Friday. At $323.10 soybean meal decreased back to $2.10 per ton after a big rally the previous week. The corn market increased slightly from the previous week’s multi-year worst prices. May corn settled at $3.46 per bushel, an increase of 2.25 cents.

Sarina Sharp is with the Milk Producers Council. Visit www.milkproducerscouncil.org for more information.