The elevated Savannah Highway landmark known as Bessie comes down anytime a hurricane or other gusty squall threatens the South Carolina coastline.

Now, the owner of the famous faux bovine is making preparations for a different kind of storm, one that’s been churning up the milk industry for years.

Borden Dairy Co., perhaps better known for its Elsie mascot, sought shelter from its bill collectors last weekend by filing for bankruptcy protection. It reported a $42 million loss for 2019 and owes between $100 million and $500 million to more than 5,000 creditors, including dozens of businesses and individuals throughout the Palmetto State.

The Dallas-based company said it plans to continue normal day-to-day operations during its restructuring.

Borden isn’t the only big milk producer navigating dire financial straits. Larger rival Dean Foods took the bankruptcy reorganization plunge in November.

Both companies, which account for a combined 13.5 percent of U.S. milk sales by one widely cited estimate, are drowning in debt they can’t repay. They’re also facing higher costs, fierce competition and unfavorable consumption trends.

“These challenges have contributed to making our current level of debt unsustainable,” Borden CEO Tony Sarsam said in a written statement last week.

Founded in 1857, the company employs about 3,300 workers and operates a dozen U.S. processing and packaging plants that can pump out nearly 500 million gallons of milk annually.

“There are no plant closures or personnel implications in connection with our filing,” Borden spokeswoman Adrienne Chance said Wednesday.

In South Carolina, she said, the company buys milk from 23 farms and employs about 160 workers, with about 100 of them based at a production and distribution site in North Charleston. The company acquired the LaCrosse Road operation about nine years ago when it snapped up Coburg Dairy from Dean Foods.

The market was already showing signs of souring when Borden took over the once-revered local brand that Charleston farmer Francis Hanckel launched with 100 cows and a horse-drawn wagon 100 years ago. Government data show the amount of liquid milk consumed nationwide has skidded more than 40 percent since 1975. The per-capita figure fell to 17 gallons in 2018. A drop-off in cereal sales is just one factor.

“While milk remains a household item in the United States, people are simply drinking less of it,” Borden finance chief James Monaco said in a U.S. Bankruptcy Court filing last week.

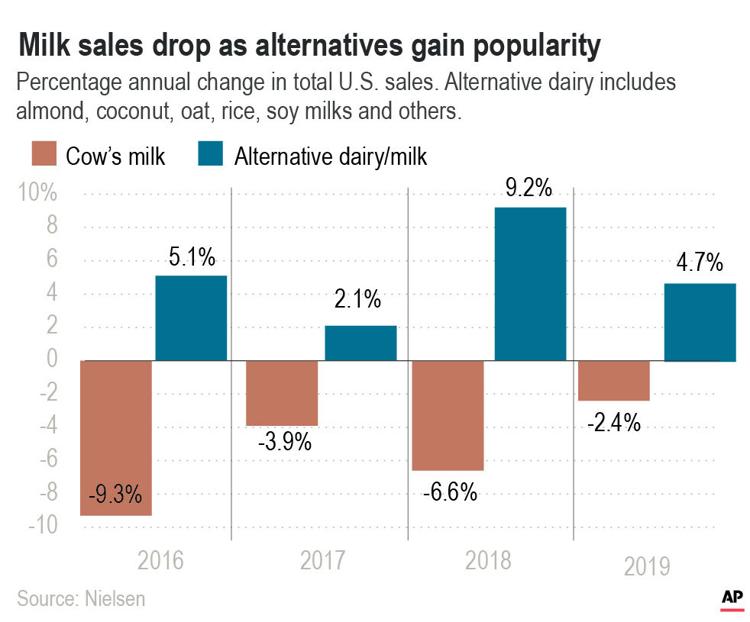

At the same time, a fast-rising crop of rival beverages, from teas to juices to non-dairy milk alternatives, have started competing for supermarket shelf space.

If that wasn’t enough, some retailers, namely Walmart, have jumped feet first into the milk processing business, forcing Borden and other rivals to keep prices low even as their supply costs have escalated.

The gradual decline of Big Dairy “has been similar to watching an accident in slow motion,” said Adam Kantrovich, an associate professor of agribusiness at Clemson University Cooperative Extension.

The fallout extends from processing plants to rural America. In court filings, Borden estimated that about 2,730 U.S. dairy farms have been put out to pasture since mid-2018. Kantrovich sees more consolidation ahead.

“This may mean some farms getting larger or at the very least having to invest in the right facilities to become more efficient while looking if there is an ability to cut costs,” he said.

As for Borden, the immediate game plan has all the makings of a straightforward bankruptcy reorganization. It said it plans to use the process to lighten its debt load, “maximize value and position the company for long-term success.”

If the company can pull that off, the Coburg Cow will likely remain on its elevated perch, as it has for about 70 years, near the original Hanckel family farm. At least until the next hurricane comes along.