Leading New Zealand based consultant and scientist Dr John Roche said this became a bigger challenge as farm size increased.

In particular, farmers needed to understand the concept of marginal milk to ensure their businesses remained robust.

Dr Roche, who is Dairy NZ’s principal scientist for animal science and spent a number of years in Australia, identified five challenges that farmers had the opportunity to influence.

The other four were climate change, biosecurity, government regulation and public sentiment.

These sat within the much broader challenge facing the world: that it needed to produce more food in the next 30 years than it had within the last 2000.

Quality of decision making

Dr Roche said on a 50-cow farm, most decisions made by the farmer were biophysical.

But as farms grew to 500 or 1000-cow farms or beyond, the biophysical decisions were made by somebody else, the farm manager or owner was making human-resources decisions, large-scale contracting decisions or future supply decisions.

But there were too many sheep in the dairy industry globally, farmers who followed what their neighbours were doing.

Farmers needed to be more disciplined in their decision making, to think for themselves and establish their own goals.

They needed to follow a robust decision-making process:

Define their own goals.

Do their own research.

Consider the consequences.

Make their own decision.

Upskill for self-improvement.

Revisit and review their decision.

Dr Roche said an example of this was in the lack of understanding of the concept of marginal milk.

The NZ industry had changed dramatically in the past 13 years. The drought of 2007-08 in NZ mimicked the drought of 1983 in Victoria in that farmers changed their entire system on the back of a 1-in-100-year drought because it might come again.

“We went from 60,000-tonne of palm kernel being fed in a 4.5 million-cow dairy industry to 1.5 million tonnes of palm kernel being fed in a 4.5 million-cow dairy industry in the space of two years,” he said.

The industry now fed about 2 million tonnes of PKE with the same number of cows.

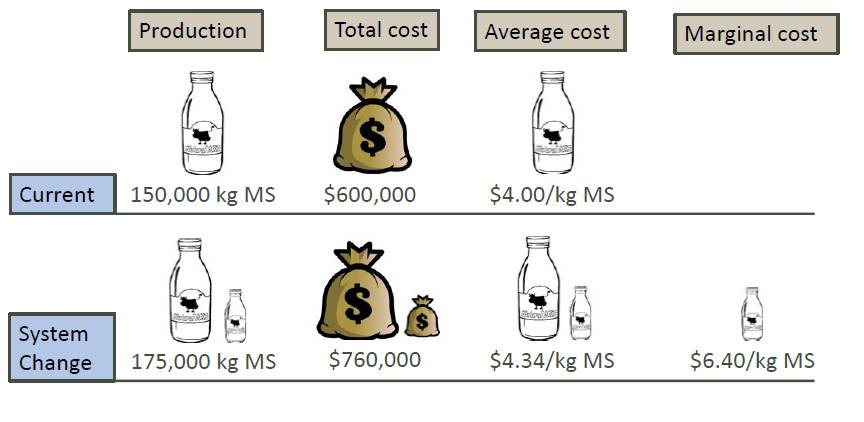

But farmers failed to understand the concept of marginal milk (see Figure 1).

“When I talk about marginal milk, I am asking, are you making money from milk or are you making milk from money,” he said.

“Is the cost of the extra milk, so when you make a change to your system, you buy more machinery, you buy more cows, you buy in feed, you do whatever, but you produce more milk, is the cost of that milk less than the revenue generated from that extra milk?”

Lincoln University research showed as farmers moved from low inputs (about 500 kilograms of supplement a cow) to medium input (500-1200kg) to high input (4.2-4.5 tonnes), the marginal cost of producing the extra milk generated by those inputs was about NZ$7.60/kg milk solids. But there were only a couple of years where NZ farmers were paid more than that for the milk.

Dr Roche gave a specific example of a farmer in NZ who had returned his parents’ farm in the south Waikato after his father became unwell. He realised the farm was not making much money, so had asked DairyNZ staff to do a whole-farm assessment and Dr Roche then looked at the economics and biophysical side of the farm.

“He had six years’ data there and so we were able to track the changes on the farm,” he said.

“Now remember years are not independent, there are going to be differences in rainfall etc, but this part of Waikato was pretty safe countryside.

“So over the six years, his total costs of production were increasing, his marginal costs were increasing.”

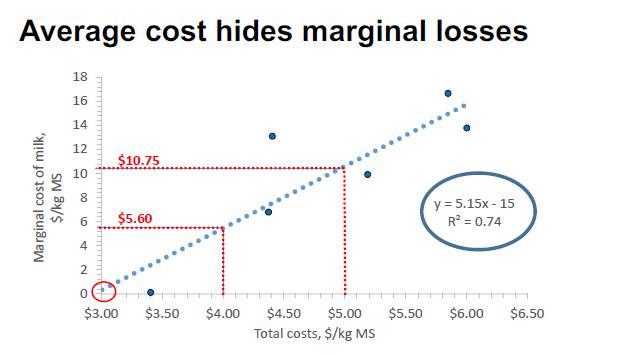

Figure 2 shows the marginal cost of milk compared with the total costs of milk on the farm.

“So for every $1 increase in average cost, the cost of the marginal milk had actually increased $5.15,” Dr Roche said

Some farmers in NZ can produce milk for less than NZ$3/kg milk solids with no supplements going into their system.

Dr Roche said so most people would not be concerned about average costs of NZ$4/kg MS. If this farm had been operating at that level of costs, the marginal milk would have cost NZ$5.60/kg MS (see lower red dotted line on Figure 2).

But the farm’s average cost was actually NZ$5/kg MS, which meant the marginal milk was actually costing him NZ$10.75/kg MS (see higher red dotted line on Figure 2).

That particular year, the farm was being paid NZ$3.90/kg MS.

“The first milk he pulled out of his system was costing him NZ$17/kg milk solids to produce,” Dr Roche said.

The bigger, the more complex the businesses, the more important it was that farmers were skilled in all of these facets of decision making.

Dr Roche also challenged farmers to think about whether they wanted to be running big, complex businesses and how that impacted on things that might be important to them, such as spending time with their family.

Climate change

Dr Roche said there was no doubt climate change was occurring.

There was a high degree of confidence in the science showing average temperatures would rise, the number of hot days would increase, cool-season rainfall would decrease and there would be increased intensity of extreme rainfall events.

But he said he was tired of the hyperbole around climate change, which was scaring people into inaction.

Farmers could respond to the changes. Options included:

Genetics – selecting animals for heat stress tolerance and increased resilience.

Infrastructure – installing fans and misters in sheds, planting more trees or creating artificial shade.

Nutrition – managing diet, for example, using feeds that cooled rather than heated animals.

But farmers should not stick their head in the sand and say this wasn’t happening.

Biosecurity

Dr Roche said many farmers were naive about biosecurity threats to their operations. He saw first hand the impact of this in Ireland when the foot-and-mouth outbreak occurred in 2001. That had created high awareness there but since then it had fallen away.

Dr Roche said Australian and NZ farmers believed biosecurity was something the government did at the borders.

In the past decade, the number of tourists and shipping containers coming into Australian and NZ had doubled but the number of biosecurity staff had remained the same.

This meant the risk was increasing. “This is no longer a case of if but when,” he said.

It was vital farmers were vigilant and took responsibility for dealing with this issue on their farms – they needed to be governors of their own businesses.

Dr Roche said there were resources available to help farmers manage this, including Dairy Australia’s recently developed biosecurity tool.

Government regulation

Dr Roche said increasing government regulation – across a range of areas including health and safety, human resources, environment, animal welfare, food safety, antimicrobial resistance and organics – was an increasing challenge for dairy farmers.

A united dairy industry was vital to help deal with this as it could ensure government decisions were science-based.

People within the industry needed to step up and call out bad behaviour to help reduce the regulatory burden.

Governments were regulators of last resort – they usually stepped in when people were doing something they should not be doing.

Public sentiment

Dr Roche said all forms of agriculture were under attack from people who were no longer connected with it.

But he said educating people about agriculture was not always the answer. One lot of Canadian research showed that people given more information about dairy farming had lower levels of confidence in it.

It was critical to recognise we now lived in a post-science world and emotion was the key to getting people to engage.

People bought the process not product, he said.

Australian dairy farmers had an emotional process to sell. Selling points include:

Producing the highest quality wholesome foods.

A trusted food safety system.

‘Free range’ animals producing low carbon footprint, nutritious food.

Taking responsibility for the environmental footprint.

Animal care of the highest standard.

A biosecurity system, second to no one.