But Mark Stephenson, dairy policy analyst at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said you would never know it just by looking at Wisconsin’s total milk production for the year.

“You couldn’t pick 2020 out of that set of trends as being an unusual year in any way at all,” Stephenson said. “But it was a very abnormal year. The way we got there was through some pretty rigorous changes.”

According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wisconsin’s milk production has been increasing each year since 2004 and has been setting a new annual record since 2009.

Last year was no exception, with the state’s dairy farms increasing total production by just under half of a percent to 30.7 billion pounds of milk.

Stephenson said the year’s total growth is thanks to a comeback that started in the latter part of 2020 and has continued into this year.

After milk prices plummeted at the start of the pandemic and a few farms were forced to dump their milk, Stephenson said dairy plants and cooperatives tapped the breaks on milk production by implementing base/excess programs, where farmers get less money for extra milk beyond their usual production level.

“Farms slowed down, you could see that very clearly. Both the number of animals dropped and milk production per cow declined,” Stephenson said. “And then two months later, we had a record-high cheese price, and we’re back on and needing to fill orders for things.”

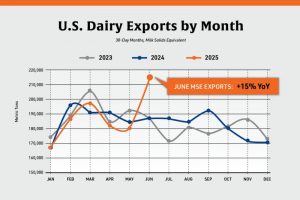

Stephenson said much of this new demand came from pandemic-related food assistance programs by the federal government. But he said dairy exports also picked up in 2020, leading some farms to add cows to their herd and dial up production per cow through management strategies.

Stephenson said this growth was also made easy by a good growing year for feed crops in 2020.

“That’s kind of led us to where we are now, with pretty strong milk production and unsurety, I think, about just how strong milk prices may stay this year,” Stephenson said.

Stephenson said he’s been concerned with how quickly producers have rushed to increase milk production without knowing how the industry and the country will recover from the pandemic.

But some dairy cooperatives in the state are still playing it safe because they haven’t seen local demand for milk return.

Mick Homb, director of milk marketing for FarmFirst Dairy Cooperative in Madison, said it was almost a year ago that his phone first started ringing off the hook with dairy plants wanting to scale back on how much milk they were buying. That forced the cooperative to put in place their own limits on milk production.

“We asked our farmers that if they were going to increase (production) above 3 percent, that they needed to call us and get permission in order to do that,” Homb said. “I think they learned early on that we were going to have way more milk than what we were going to be able to sell, and we were going to be in for a lot of months of having to sell distress milk (at a lower price) to make sure we didn’t have to dump any milk.”

A year later, Homb said FarmFirst still has that policy in place because they’re still having to sell some milk below market price.

He said many small cheese plants in the state have gone from being steady consumers to buying milk sporadically because they’re struggling to move their own inventory.

“It seems like instead of planning for the future, two to three months in advance…they’re only reaching out a week or two. Because with everything going on, you just don’t know where it’s going from here. And I think that has changed the landscape of how people plan and produce and predict what they’re going to do,” Homb said.

But Homb said he knows many dairy farmers are looking for ways to grow their production in 2021. He started getting calls last month from producers hoping to join the cooperative after their milk buyer told them they wouldn’t take on more milk.

“I have not taken on any new farmers in over a year and still can’t because how can you take new milk on when you’re still selling milk at distressed prices?” Homb said. “I think it’s gotten better but from who I talk to and listen to, I think everybody is still trying to get rid of some of their milk.”

Stephenson said almost all milk cooperatives in the state are having similar debates as they think about the months ahead.

“We’ve got to be prepared to tap on the brakes a little bit and slow down. That’s on the horizon,” Stephenson said. “We don’t want to be in the situation that we were in last year when we hit the brakes pretty hard and then all of a sudden discovered this new demand for cheese needed for food box programs. We’d like to be able to meet the need in a more steady and uniform way.”