When the dairy farmer Shane Hickey calculated his hourly rate of pay at just $2.46 last year it prompted a wave of outrage and sympathy. Consumers vowed to change their purchasing habits to support small, independently processed milk instead of the $1-a-litre offerings in the major supermarkets.

But among other farmers, the conversation was very different. “I got quite a few phone calls from farmers asking me how I made $2.46,” Hickey said.

“They were quizzing me … One guy was losing $500 a day, $15,000 a month. Another guy just up the road, they’re losing $10,000 a month.”

The Australian dairy industry was already in crisis when drought struck key production regions in Victoria and New South Wales in 2018. Now farmers like Hickey say they are barely hanging on.

He has reduced the number of cattle on his 200-acre property at Kyogle in the northern rivers region of New South Wales from its peak carrying capacity of 150 to 85.

It’s a situation repeated across the country. You can’t run a dairy farm without water — it takes 1,000 litres of water to make one litre of milk — and there is little to be had.

This is the latest in a string of setbacks that have faced the Australian dairy industry in the past decade. The number of dairy farms in Australia has fallen from 7,511 in 2010 to just 5,669.

Most of those problems can be traced back to 2014, when a combination of the lifting of quotas for European milk producers and sanctions against one of their biggest markets, Russia, over the downing of MH17 created an oversupply that led to a downturn in the global milk solids price.

Milk solids are the dried powder of fats and proteins that remain once all the water has been evaporated. Milk is usually about 12% solids, and milk prices are based on milk solids.

I was speaking with another local farmer just the other day, we are both saying we don’t know whether we will survive

Phil Ryan

In Australia, Coles and Woolworths took advantage of that oversupply to bargain down the wholesale price of milk for their own-brand products, which they had begun selling for $1 a litre in 2011.

In April 2016 the major processors Murray Goulburn and Fonterra stepped down their milk supply contracts mid-season after overestimating the global market that saw the companies facing shortfalls of up to $200m. The price offered to farmers was reduced by about $0.80 a kilogram of milk solids for Murray Goulburn and $0.60 for Fonterra and the cut was applied retrospectively, meaning that for the last two months of the contract, payments to farmers were cut by almost two-thirds. The sudden drop in cashflow drove some farms out of business..

Decades of industry advice to Australian farmers was to invest more and produce more when bills were mounting in the hope that greater efficiencies would improve the bottom line. At the same time, farmers were urged to reduce debt to reduce their exposure.

When the drought is on, they can do neither.

“Chasing that efficiency that we all got told was how we were supposed to make our money, because we weren’t going to get more money for our milk, has actually increased our cost base and added more risk into our business,” dairy farmer Phil Ryan said.

A report by the Australian Competition Consumer Commission last year blamed the farm-gate price on “power asymmetries” between supermarkets and processors, and processors and consumers, but said it “did not obtain any evidence that supermarket pricing, including $1 per litre milk, has a direct impact on farm-gate prices”.

This is because farmers are paid the same milk price whether it ends up in $1 milk or not, with prices set by processors such as Murray Goulburn.

On Monday Woolworths announced that it was increasing the retail price of its own-brand milk by 10c a litre on two- and three-litre bottles, with the increase to be passed on to the farmer. About 450 farmers are expected to receive a price increase, which will work out at less than 10c per litre produced.

The agriculture minister, David Littleproud, had been pushing the idea of a temporary levy for drought-affected farmers since September and welcomed the news, calling on Coles and the German supermarket chain Aldi to follow suit.

But the government response many farmers remember is that of the prime minister, Scott Morrison, who said: “I want to ensure we can ensure the sustainability and viability of our dairy sector, but not doing that at a cost to mums and dads pouring milk on their cornflakes.”

Ryan runs a 200-cow operation near Bega on the NSW south coast, supplying Bega Cheese. He is now just above 50c a litre at the farm gate, roughly the same as it is costing him to produce. He says it’s not fair to put the burden of reducing the cost of living on farmers who cannot pay their own bills.

Ten cents a litre or 20 cents a litre isn’t going to break most household budgets, he said. “If [Morrison] genuinely doesn’t think that Australian families can afford that then there’s a much bigger problem than the dairy industry. It’s an issue for raising minimum wages.”

Ryan worked in IT in Sydney until 2007 and is preparing to take a second job to support his operation if the drought does not break in the next 12 months. The mental health toll is high. Half of the farmers Ryan knows admit to dealing with depression and anxiety. Many more bottle it up.

“Six out of 65 farms locally have sold in the last 12 months,” he said. “I was speaking with another local farmer just the other day, we are both saying we don’t know whether we will survive … we have got four-month-old bills that we can’t pay.”

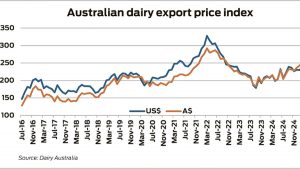

Rabobank’s senior dairy analyst, Michael Harvey, says the milk price in Australia is likely to increase next financial year in response to a shortage on global milk markets, which will provide “some comfort” to drought-affected farmers.

The global commodities price is expected to settle at $6 a kilo of milk solids over the medium term.

“You need to plan your business and structure your business for that being an average milk price going forward and if you can make money at that then you have got a sustainable future,” Harvey said.

There is growing demand for dairy products, particularly in China, but the market favours those with the lowest cost of production. Some high-value products, such as baby formula, which is bought by the boxful from Australian retail shelves and shipped directly to China through informal channels, require additional ingredients that cannot be sourced in Australia even if the domestic milk production increases.

Farmers were fed a big load of shit

Shane Hickey

Australian farmers are able to be globally competitive if they can rely on rain-fed pasture growth rather than grain or hay feeding. Those conditions, once considered normal, are becoming less frequent due to climate change.

Farms that rely on irrigation, such as those near the Murray River in northern Victoria, are less viable, and many have already been listed for sale.

Labor’s agriculture spokesman, Joel Fitzgibbon, has said he will ask the ACCC to investigate introducing a floor price for milk to ensure farmers can cover their costs. Littleproud says the idea is unworkable without a quota system, which would undo the deregulation of the dairy industry after two decades.

The chief executive of the advocacy group Australian Dairy Farmers, David Inall, met Fitzgibbon to discuss the proposal this week. He said farmers are increasingly worried that farm-gate prices don’t cover production costs and encouraged them to “work with Dairy Australia on strategies to keep their cost of production low while also capitalising on export and other opportunities”.

Some Australian farmers advocate the return to a highly regulated quota system, like the Canadian model. The Canadian academic Bruce Muirhead describes the current Australian system as “completely unsustainable” and based on neoliberal agricultural philosophies about the uncapped power of investment and technology to achieve greater efficiencies

Or, as Hickey puts it: “Farmers were fed a big load of shit.”

“They were told to get bigger, get economies of scale, buy all this equipment that’s really expensive to maintain … get all these expensive commodities in to make your cows produce more milk.

“Now the commodities have disappeared, hay is through the roof, all your soy bean meals are nonexistent, so all these farmers that have listened to the experts are screwed.”