Sales and new products are up, say industry experts, because people want alternatives to animal products for health and environmental reason and the industry is offering a greater variety of non-meat choices, with flavors and textures often mimicking animal products. And it’s getting product placement in many cases right next to animal-based products.

“I think it’s important to showcase plant-based options to an audience who may not be seeking them,” Kalie Marder, co-owner of Renegade Foods, with production facilities in Sonoma County, said. “One way to normalize vegan food is to put it in the grocery store where you will find its animal counterpart. Consumers tend to be presented with a meat-free option that still meets their expectations.”

Anja Raudabaugh, CEO for Western United Dairies, said any weakening of the standards around butter fat, for example, threatens to weaken the formulaic price, “or at least it has the potential to.”

“Take it to its logical conclusion. If products can fill shelf space that claim to be butter, you’re not only losing shelf space, but you’re losing value at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (which sets the price for butter),” Raudabaugh said.

The lobbying organization and think tank represents nearly two-thirds of California’s dairy farms.

The California dairy industry, which employs 286,000, has lost 2% of its market share in the past eight years.

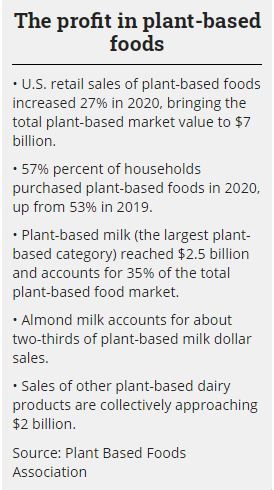

Meanwhile, in 2020 plant-based yogurt sales grew 20%, almost seven times the rate of conventional yogurt; plant-based cheese grew 42%, almost twice the rate of conventional cheese; and plant-based eggs grew 168%, almost 10 times the rate of conventional eggs, according to the Plant Based Foods Association. The plant-based egg category grew more than 700% from 2018, 100 times the rate of conventional eggs.

“Our most recent data that covered the 2020 grocery year shows plant-based food sales were up another 27 percent. That has been the way it has been year-over-year for the last six or seven years with tremendous double digit growth,” said Michael Robbins, who handles policy for the association. “It’s outpacing all other sectors of the grocery store.”

North Bay providing alternatives

Amy’s Kitchen in Petaluma is a powerhouse in the vegetarian/vegan world, having been in business since 1988.

“We never could have predicted that one-day vegetarian and vegan would become mainstream and on track to surpass animal protein alternatives someday,” Andy Berliner, Amy’s co-founder and CEO, told the Business Journal. “Consumers are more educated about food choices and the impact diet has on their health and the health of our planet. They’re seeing the data that a plant-based diet can improve personal and planet health. Now our biggest challenge is keeping up with the demand.”

He said demand for Amy’s products “surged 100% in 2020.” Berliner attributes this to people stockpiling during the pandemic and wanting to eat healthier. Revenues in 2020 were about $600 million.

“We expect a record year in 2022 because of investments we’ve made in more production facilities — new locations in San Jose and Goshen (in Tulare County) — and people,” Berliner said.

The company has 136 products on the market, and in a normal year launches six to 12 new items.

“Amy’s is unique in that everything is made from whole, organic ingredients and cooked in real kitchens much the way you would at home with a lot of love,” Berliner said.

Innovation, like most industries, is a key to success. Ten-year old Wildbrine and WildCreamery in Santa Rosa just released an oat butter and soon will have a quinoa-based sour cream.

“We have made cultures for plant based items that are derived from the same byproducts by fermenting plants,” co-owner Chris Glab said. Products are usually found in grocery stores mixed in with similar non-plant based items.

Glab said in the United States in the 12 months ending Jan. 24, 2021, compared with the previous 12 months:

• Plant-based cream cheese grew 2.3 times faster than traditional dairy cream cheese (45.1% vs 19.7%)

• Plant-based sour cream grew 3.8 times faster than traditional dairy sour cream (53.8% vs 14.8%)

• Plant-based butter grew 6.6 times faster than traditional dairy butter (133.3% vs 20.3%).

While Renegade Foods has only had plant-based products on the market since 2020, research and design was a decade-long process. The company is headquartered in Berkeley, with production taking place in Petaluma.

The company produces non-meat salami that is all plant-based. Marder would not reveal what future products will be, but said to expect something from Renegade in 2022 that could be found in the deli section.

“Renegade is tailored to the flexitarian; the consumer who is looking to consume less meat,” Marder, the company’s co-owner, said. “We have the same mouth feel and flavors of the meat analogue.”

Those tracking sales of non-meat products say people who identify as vegan or vegetarian are not eating more, it’s the flexitarians who are moving the needle. These are people who are eat less meat each week and more plant-based foods. They may also be using soy or some other milk instead of cow milk.

The dairy struggle

As one food segment grows, it often means another is declining. That is what dairy farmers are worried about — losing even more market share.

The number of dairy farmers is on the decline. According to the American Farm Bureau Federation, “Since 2003, the U.S. has lost more than half of its licensed dairy operations, now just shy of 32,000 dairy operations.”

Even so, the agency reports milk production in the U.S. in 2020 was 223 billion pounds, an increase of just more than 2% from 2019. Butter production increased in 2020 with so many people at home baking during the pandemic.

The dairy vs. non-dairy struggle has landed in the court system.

Some North Bay dairy farmers backed the lawsuit the California Department of Food and Agriculture filed against Miyoko’s Creamery of Petaluma. Miyoko’s won that fight in U.S. District Court in San Francisco in August, thus allowing it to use dairy-centric phrases in its advertising.

For Raudabaugh with Western United Dairies, Miyoko’s First Amendment fight wasn’t a case of big dairy versus the small vegan startup, but about standards of identity that are key to nationalized price points, and the import and export markets.

“Those standards are important. When we make trade agreements, we want to make sure our trading partners are adhering to the same standards of identity,” Raudabaugh said, adding that the formula for butter prices, which is tied to fat percentages, is set by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. “This is really where the fundamental concern of the U.S. dairy industry comes from.”

Tawny Tesconi, executive director of the Sonoma County Farm Bureau, a local industry group, has been outspoken in her distaste for Miyoko’s Creamery’s tactics, calling owner Miyoko Schinner a hypocrite for what she sees as attacks on the traditional dairy industry.

“I find it very hypocritical that (Schinner) slams animal agriculture, but wants to mimic the names of animal agriculture products,” Tesconi said.

When Miyoko’s won her First Amendment case, using the Animal Defense League attorneys, it further proved to traditional dairy industry insiders that the vegan creamery’s business model is as much about taking down animal-based dairy as it was a fight for free speech.

“She has been very outspoken against animal production,” Tesconi said. “She has been outwardly promoting a reduction or total termination of animal protein — that has really been her mantra. She has been very forthcoming about her belief that there shouldn’t be animals raised for agriculture.”

What Schinner told the Business Journal is she believes there are better ways to raise animals.

“My hope is that we can convince farmers that participating in a compassionate future of food will allow them to stay connected to the land and even evolve the relationship they have with their cows,” Schinner said.

She added, “Any time there is a shift in technology or industry, there will be a battle between the old way and the new. However, dairy farmers, too, are waking up to the truth behind some of their woes—consolidation. It wasn’t the plant-based industry or veganism that put over 30 farmers out of business in the Northeast, it was Danone (a consumer packaged food and beverage company based in Broomfield, Colorado,) consolidating.”

Dairy industry officials acknowledge they have work to do. It’s work that’s ongoing, Raudabaugh said, including efforts to reduce methane gas emissions and water pollution. She said the industry is working with partners in academia to be better stewards of the environment and have reduced methane emissions by 47% in the past decade.

Raudabaugh said most of the farmers Western Dairies represents are also in plant production. She said it doesn’t do the world any good to focus on eliminating dairy or its dairy alternative competition, emphasizing she’s disappointed that’s where the conversation has gone.

“We have to respect the market spaces we all hold, because that’s the key to true nutrition access,” she said.

For Schinner, she is ready for the next battle, believing those who raise and sell animal products for a living are on the attack.

“The battle at the legislative level will become heated as subsidies for animal agriculture start to become challenged by not only activists, but lobbyists for the alt-protein industry as well as some legislators themselves. We are headed for some interesting times when we unravel unfair practices that prop up certain industries while suffocating innovative new technologies,” Schinner said. “These battles will cover everything from nomenclature to subsidies to ag-gag laws that actually protect the incumbent industries and stifle free speech that aims to expose some of those harmful practices.”

Robbins with the Plant Based Foods Association said the push back is from ranchers, pig farmers and dairy ranchers.

“Rather than try to compete on a level playing field, they are constantly trying to undermine the plant-based food industry,” he said. He pointed to the First Amendment struggles like what Miyoko’s Creamery went through. (Schinner is a founding board member of PBFA.) “It plays out in courts, in state legislatures, with Congress and the FDA. It is something we are very engaged in.”

Robbins said companies like Tyson, Nestle and Cargill “are our allies.” He added, “They see consumers moving toward plant based and they are looking to diversify their lineups.”

Consumer demand and feed prices all play a role in the business side of dairy farming. What steps individual farmers will take to remain viable remains to be seen.

Scott Dicker, marketing analyst for the wellness-focused data company SPINS, believes consumers wanting more plant-based foods is having a ripple effect.

“It is causing the meat and dairy industries to be more cognizant so they are claiming more sustainability by saying they are certified humane and organic,” he said.