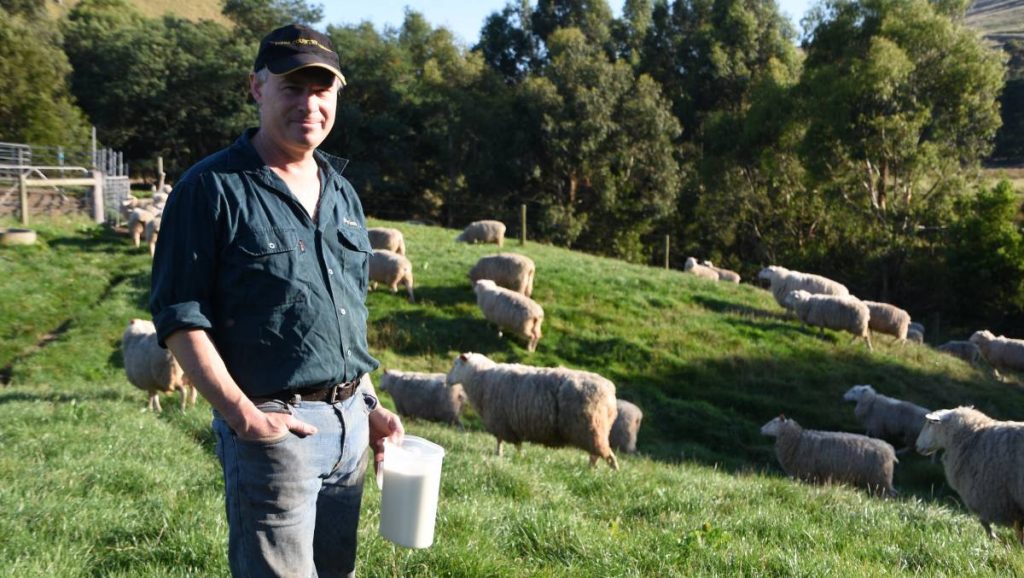

The sheep dairyman knows the visiting reporter has endured a lifetime of gushing dairy cow showers.

“See this bucket?” he says, sweeping a ewe’s miniature manure pellets into a white chemical pail with a hearth brush.

“We’re lucky to fill it in a week.”

Of course, it’s not just the manure; almost everything about sheep dairying is on a smaller scale.

Burke and wife Bronwyn milk 150 ewes on about 60 useable hectares in a 12-sheep-aside swingover.

The 1960s-era concrete-block dairy is just a hundred metres or so further up the driveway from their boutique cheesemaking facility, Prom Country Cheese.

The ewes have two rather than four teats and production is less than a tenth of what you’d expect from a dairy cow, peaking at about 3 litres a day per ewe.

The volume is too small for the reliable operation of automatic cup removers but each litre packs a punch, with a fat content between 5 and 8 per cent and protein at 6 to 7pc.

The sheep graze the almost perpetually lush green grass of Moyarra, South Gippsland, which has a rainfall high enough to be forgotten.

“It’s about an inch a week,” Mr Brandon said.

“We don’t bother recording it anymore.”

The ewes’ diet is supplemented by homegrown hay and just a sniff of grain to encourage stress-free milkings.

In so many other ways, it’s the same as any bovine dairy: there’s constant vigilance for mastitis, youngsters need to be trained alongside wiser, older milkers and the males are a pest if they make it into the dairy.

Each milking takes two to three hours and, for five months a year, they’re milked twice a day.

It’s a strictly seasonal operation, with a nine-month lactation, after which all the milkers are dried off.

And, while the average ewe weighs about 80kg, a fraction of the 500-700kg frames of Holstein dairy cows, the workload is every bit as heavy.

As well as the milkings, feeding, breeding and pasture work associated with dairy cows, there are added routine crutching and shearing chores.

If that didn’t keep the couple busy enough, hours are spent cheesemaking and selling product as well.

“It’s just as well there are 24 hours in a day because we can fill all of them during the peak times,” Mr Brandon quipped.

Months can pass between social outings for the Brandons and even wedding anniversary dinner is on hold until the ewes are dried off for the season.

But sheep dairying, particularly if you have cheesemaking skills, suffers less of the uncertainty associated with cow dairy businesses.

The Brandons certainly don’t monitor global commodity prices, exchange rates and processor opening prices with the anxiety of many dairy farmers.

Being part of a niche industry does, of course, bring some challenges, like sourcing suitable genetics.

“You can’t just go out and buy milking sheep in Australia so we’ve had to do a lot of selection over time,” Mr Brandon said.

The Brandons started off with traditional Coopworth, Dorset, Corriedale dual-purpose breeds crossed with East Friesians.

Although the East Friesian is the main milking sheep breed, it has different characteristics in Australia.

“The East Friesian was brought to Australia about 30 years ago to increase the milk of prime lamb mothers so they’ve been selected for the prime lamb industry, not milking characteristics,” Mr Brandon said.

“So things like temperament, conformation of the udder and teats are what we’ve been selecting on.

“Milk quality is the underlying criteria but not the critical one for us.”

During Prom Country Cheese’s preparations to make Victoria’s first commercially-produced raw milk cheese, about 20pc of the milking flock was culled.

Any ewes with health issues that could affect the cheese quality simply had to go.

But Mr Brandon seemed unfazed by the enormity of the transition.

The ewes average twins so, with 300 lambs a year to serve as replacements, there’s the opportunity to sell prime lamb while culling heavily for rapid genetic gain.

“Lamb is a side business for us,” Mr Brandon said.

“They’re a bit slow to grow out and take nine to 10 months to grow out but are not fatty.

And while the sheep are bred primarily for milking, they are also heavy producers of carpet-grade wool.

“Every milking sheep in the world needs shearing because they’re selected for milk not wool-shedding ability,” Mr Brandon said.

“The wool grows very fast but it’s a coarse wool that really just covers the cost of shearing.”

Crutching was far more important and extensive – extending right up the belly – and carried out three times a year because the udder must be kept free of wool.

But one thing was clear, the Brandons wouldn’t swap ewes for cows any time soon.