Key points:

- The state government is under pressure to review recent flood disasters, considering the impact of developments in river catchments

- Farmers who have experienced successive floods say the inundations behaved in unusual and disastrous ways

- Flood-prone communities want action to better protect them from worsening and more frequent events

Agricultural organisation NSW Farmers wants an independent review to consider how flooding has changed across the state, especially in the wake of last year’s deadly devastation at Lismore in the Northern Rivers and Eugowra in the Central West.

“We have in front of us a once-in-a-generation opportunity to build back better from a major, widespread disaster, and set up a process that will protect people, property and improve planning certainty into the future,” president Xavier Martin said.

Mr Martin believes understanding floods and planning for them has not kept up with the rate of development across the state’s river catchments.

“Levees, roadways or other structures built on the landscape alter the movement of floodwater, and we’re concerned that this is why we’re seeing unprecedented flooding in new places,” Mr Martin said.

He said it is time to face the real consequences of those decisions.

“Flooding rains can’t be avoided, but we can avoid exacerbating the problem, and we can prevent future loss of life, of livelihoods, of property and of business.”

Disrupting natural flows

One of Australia’s most complex and dangerous flood plains lies on the outskirts of Sydney.

The Hawkesbury Valley has been smashed by six floods over the past three years.

But before 2020, the region had gone 30 years without a major flood, which locals say lulled planning authorities into a false sense of security.

Richmond turf farmer Jess Micallef said tens of thousands of new homes have exacerbated inundations in an already flood-prone area.

“Every time that a development goes up, a road, anything like that makes a huge difference … whether it be how quick we flood [because] there’s not as much soaking ground anymore,” she said.

She is among those who want more done to protect thousands of at-risk homes, businesses and farms.

Floods have done extensive damage to her farm, and those nearby.

Erosion has torn a 300-metre-wide hole in the riverbank, and in last year’s floods water broke through and inundated formally dry land, she said.

“The process of the water is not a natural process now. It’s been been played with, it’s been tampered with and we’ve done nothing about it.”

Ms Micallef is concerned there are no concrete plans on how to protect this community.

“If you change things on one side you must change things on the other, otherwise there’s going to be a disaster and there has been a disaster. Multiple times,” she said.

The Minns Government has ruled out raising the Warragamba Dam wall, a project it claims will not guarantee downstream communities will be safe from floods, and would do damage to heritage and the environment.

Instead, it will look at more immediate options such as building levee banks, improving evacuation routes and emergency communications.

Flood plain populations grow

The Hawkesbury City Council rued the decision to rule out the dam wall upgrade.

“You need to step up to our community and tell us what you’re going to do to protect us,” Liberal party councillor and Mayor Sarah McMahon said.

“We still need a longer-term flood mitigation option and the raising of the Warragamba Dam wall proved by independent data that would lower floods here in Windsor by three to four metres.

“That means hundreds of homes, farms, small businesses not impacted.”

She said far more people are living in flood-prone areas.

“Because we’re moving more people out and we have to cater for more people who are also stranded — the risk does increase. Every single life means that risk increases.

“We end up as the end result of all that development, so we need to have a broader conversation.”

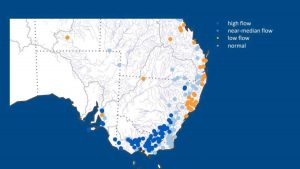

NSW Farmers want a review to draw on local knowledge and state-of-the-art technology such as aerial laser mapping, known as LIDAR, to understand the landscape and how future events could play out.

It would take into account both legal and illegal works.

Water management specialist Celine Steinfeld from the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists said that would fill a knowledge gap.

“Planning on flood plains has been increasingly favouring the development of river systems and the real challenge of managing the flood risk and ecological element I think is still yet to come,” Ms Steinfeld said.

“The big opportunity here is we can ensure flood plains can safely pass water through them and we can have agricultural and ecological systems working together.”

But she said living in such areas always comes with risks and uncertainties.

In a statement, a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Planning and Environment said the government made an election commitment to proactively plan and mitigate against the impacts of floods by “drafting new rules and updating planning processes to stop inappropriate developments on dangerous flood plains throughout NSW”.

The statement said, in line with the recommendations of the independent 2022 Flood Inquiry, the department would work with the NSW Reconstruction Authority to create a risk-based approach to flood planning.