The co-operative says its terms and conditions of supply are designed to ensure local environments and communities are protected for generations to come.

“So, it’s important that all suppliers play their part,” group director Farm Source Richard Allen told Rural News.

His comments follow a High Court ruling that rejected a bid by Marlborough farmer Philip Woolley to claim $2 million from the co-op for uncollected milk that he had to dump in 2014.

Woolley was seeking $1.8m from Fonterra to cover the loss of milk, sharemilker costs and an enquiry to find out how much Fonterra should pay towards the $3.4m cost of receivership.

In 2014, Woolley put his company Awarua Farm Limited into voluntary receivership after racking up nearly $200,000 in legal fees, upgrading the effluent ponds and getting little income from the 2014 dairy season. The receivership ended in Sept 2016 with $274,688 repaid to unsecured creditors.

Justice Andru Isac ruled that Fonterra was not unreasonable in refusing to collect milk from Woolley’s farm.

He also ruled that Fonterra’s notice suspending milk collection was properly issued and effective.

Woolley’s “unlawful conduct” and failing to meet Environment Court’s enforcement orders resulted in his losses, Justice Isac ruled.

Allen says the co-operative is pleased with the outcome of the case.

“Strong healthy local environments and communities are the foundation for sustainable, profitable dairy farming,” he told Rural News.

“As part of ensuring we’re creating a sustainable future for our co-operative, our farmers and our communities, Fonterra reserves a right to suspend collection of milk from farms that do not meet the extensive environmental and other compliance standards agreed to in our terms and conditions of supply.”

Woolley, who owned two other farms, had several run-ins with the Marlborough District Council (MDC) with his obligations under the Resource Management Act, resulting in several prosecutions for effluent management breaches.

By 2011, Fonterra was coming under pressure to deal with Woolley as media reports emerged about his offending.

On July 30, 2011, Fonterra sent a letter reminding him that if his farm effluent systems didn’t comply with council regulations or the co-operative’s sustainability requirements, then milk collection would stop.

Over the next two years, council and Fonterra staff tried unsuccessfully to deal with Woolley to rectify effluent management issues.

In August 2013, the Environment Court found Woolley in breach of his resource consent, pointing out that it was “one of the most serious cases” brought to its attention. He was banned from milking cows on Glenmae Farm unless he got an engineer’s certificate approving his effluent pond was well-functioning.

In July 2014, Woolley resumed milking cows at the property in breach of the court enforcement order obtained by MDC. This prompted MDC to write to the then Fonterra chief executive threatening legal action if milk was collected from the farm.

By the end of August 2014, up to 20,000 litres of milk was being dumped every day into pond 1 at Glenmae, which had become a putrescent problem of its own.

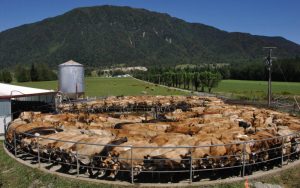

Around this time the number of cows on the property peaked at about 1200. Woolley alleged Fonterra was in breach of the supply contract by refusing to collect milk from Glenmae in the 2014-15 season.

Woolley claims that he complied with the terms of the enforcement order on 5 September 2014, when he obtained an engineer’s certificate. He says that afte that date Fonterra was not entitled to maintain its suspension of milk collection and that it exercised its contractual discretion to do so unreasonably. However, Justice Isac disagreed.