At the start of 2020, Minnesota’s livestock farmers looked out and saw a fairly good year ahead. Dairy farmers had just enjoyed a price rebound that lifted their financial hopes while corn and soybean growers feared another year of low prices and abundant crops.

Today, nothing looks like it did a year ago for Minnesota’s food-growing industry, the nation’s sixth-largest by revenue. A wrenching disruption upended hog farming, and milk producers teetered as the coronavirus pandemic spread last spring.

But corn and soybean growers flourished, after extreme weather and a surge in exports bolstered prices. “It turned out to be a way better year than what we thought it was going to be,” said Tim Little, a corn and soybean farmer near Faribault.

The pandemic threw the U.S. economy into recession for the first time since 2009 and changed the trend line in every segment of farming. And yet, farmers, food processors, distributors and grocers kept Americans fed even as eating patterns underwent a rapid shift driven by the need for people to spread out and stay home to slow the virus.

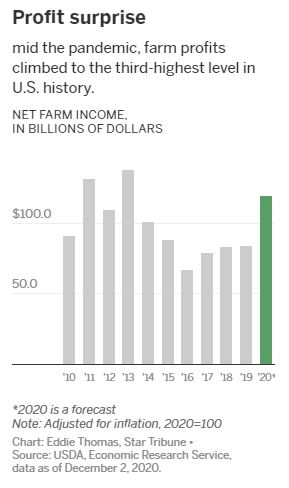

Congress and President Donald Trump approved federal assistance of unprecedented size to farmers to offset effects of both the pandemic and a trade war that had stretched into a third year. The result: Overall farm income rose 43% in 2020 to its third-highest level ever, surpassed only by 2011 and 2013.

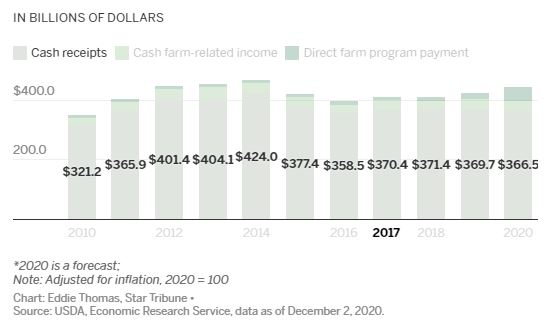

But even without that assistance, cash receipts for crops and livestock came in just 5% below the average of the past decade as prices surged near the end of the year for corn, soybeans and pork. And Minnesota farmers benefited in ways that those in other states didn’t.

Iowa and Nebraska, among other states, endured weather disasters that depressed crop yields. Minnesota’s farmers escaped all that and put up some of the best production numbers in the country. And now, in the months between harvest and planting, they are using their profits in ways that haven’t been seen for several years. They are paring debt, updating equipment and making improvements to land and facilities.

“We had all of these years of really rocky farm income and now we had the coronavirus on top of that,” said Megan Roberts, a University of Minnesota agriculture extension economist who farms near Madelia, Minn. “It is nice that I’m sitting here now having a conversation about what was on average an unexpectedly decent year for farmers.”

Farm revenue components

Receipts for crop and livestock sales neared the 10-year average in 2020, but a huge infusion of government aid lifted overall revenue in the farm sector.

Spring

For all farmers, 2020 began with hope because of a break in the trade war the U.S. started with China in May 2018 that led the Chinese government to stop buying most U.S. farm products. On Jan. 15, Trump and China’s top trade official signed a deal in which China would resume purchases.

Hog farmers were particularly happy. China had been the largest buyer of U.S. pork, accounting for about 25% of farmers’ exports before the dispute.

“We had quite a bit of optimism at that point,” Dave Preisler, executive director of the Minnesota Pork Producers Association, said as he recalled the start of the year.

“A big part of the reason was the Chinese agreement and what looked to be some pretty promising export growth,” he said. “We were geared up to look at a good year, not a great year, but a good year.”

China was also the No. 1 destination for U.S. soybean exports and one of the top buyers of corn. But it would take months for China to begin to live up to the purchase targets set forth in the deal. And just over a week after the trade deal was signed, the U.S. and the rest of the world began confronting the coronavirus that originated in China.

“We had come off the second of two wet years and commodity prices were still low,” said Brian Thalmann, a farmer near Plato and president of the Minnesota Corn Growers Association. “And it appeared there was going to be a little light at the end of the tunnel. Then COVID hit. That turned everybody upside down.”

Even before the food supply chain began to feel the effects of consumers staying at home, farmers noticed the change in prices and demand for ethanol, the vehicle fuel derived from about 40% of the nation’s corn production.

Ethanol facilities began to shut down, sending corn prices lower. And there was a knock-on effect: The market for carbon dioxide — a byproduct of ethanol refining that is put in tanks and sold for use at food storage facilities and to put the fizz in beer and other drinks — flew out of whack.

In mid-April, pork-processing plants had become hot spots in the COVID-19 outbreak, leading their owners to close them for deep cleaning and equipment upgrades to isolate and protect workers.

Because processors take hogs at a certain weight and size, the closures created backups in the supply coming from farms. Feeding pigs past that weight is a losing proposition for farmers and some were forced to kill fully grown animals because there was no market for them.

“The bottom really fell out of the hog market,” Roberts said. “It was one of the hardest-hit industries in agriculture.”

A demand slowdown also hit dairy producers, forcing farmers in some states to throw milk away because dairies refused to buy it. In Minnesota, where a greater proportion of the milk supply goes into the production of cheese, that didn’t happen.

Amid such an unpromising start to the year, farmers caught a break from Mother Nature.

“The one positive was we had a nice spring,” Thalmann said. “Farmers were able to get the crop planted on time or ahead of schedule.”

Summer

The good weather continued through summer and commodity prices remained depressed, in part because the pickup in exports expected from the thaw in U.S.-China trade relations hadn’t materialized. At the end of May, China had purchased less corn from the U.S. than it did in 2017, well below the target set in January.

In Washington, Congress and the Trump administration crafted a coronavirus aid package that gave farmers about $32 billion in direct payments, dwarfing the usual government assistance for crop insurance and conservation of around $7 billion to $10 billion annually and also the aid crafted in 2018 to offset trade losses from the fight with China.

At year-end, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s data would show that nearly all the revenue gain farmers as a whole experienced in 2020 was because of the higher amount of government aid. But as the first wave of that money flowed out during the summer, the main source of farm revenue — cash receipts for crops and livestock — also started to pick up in several key segments.

With pork plants running at normal capacity by midsummer, prices stabilized. Similar disruptions also prompted rebalancing on turkey farms. Even the carbon dioxide shortage had eased by July.

Then, in August, an inland hurricane known as a derecho swept through Iowa, Illinois and Indiana, leveling buildings, corn and soybean plants. The destruction reduced the output on 20% of Iowa’s farmland and finally began to drive commodity prices upward.

Fall

Through August and into September, China’s purchases of U.S. farm products accelerated. In about a four-week period just as harvest began, corn and soybean prices climbed 20%.

For about four years, farmers had been paid less than $8 to $9 a bushel for soybeans, below the break-even point for many. When prices broke above that, many farmers sold their harvest directly to market and emptied bins. “A lot of beans sold in that $9 to $10 range,” said Little, the Faribault grower.

By late September, the pork market was also back in balance and processors avoided further workforce disruptions from the virus. “Demand for pork both domestically and for exports has been very good,” Preisler said. “A big part of it is simple market economics. With people being at home more, there’s been a huge increase in interest in barbecue and smoking, meals that take a little more time to prepare.”

While a snowfall in mid-October slowed the harvest, most Minnesota farmers finished their work early. And a long dry period in November and early December gave them plenty of time to set up for 2021.

“I think a lot of fields are in really great shape in advance of spring planting,” David Meyer, founder and chief executive of Titan Machinery, the West Fargo, N.D.-based implement dealer with more than 100 outlets around the Upper Midwest. The company saw a surge in sales of tractors, combines and other equipment in the early fall and raised its profit outlook for the end of the year.

On Dec. 31, soybean prices surpassed $13 a bushel as global supplies fell to the lowest level in seven years and drought threatened the crop now growing in Argentina. Last week, a Cargill Inc. executive said distributors are on the verge of rationing soybeans. Minnesota farmers are spotting a new effect: rising costs for seed, fertilizer and other materials.

“I see our inputs taking off,” Little said. “It just makes me wonder where we’re going.”

Evan Ramstad • 612-673-4241