Dairy Outlook: Cows produce more milk and less methane compared to 15 years ago.

Since the introduction of frozen bull semen in the 1950s, dairy farmers have been using artificial insemination to improve the next generation of their dairy herds and increase farm safety by eliminating mature bulls from their farms. During the next six decades, genetic improvement largely remained the same, as identifying the succeeding generation of elite bulls required eight years of elaborate progeny testing.

“That all changed in 2008, when genomics was introduced to the dairy industry,” says Corey Geiger, lead dairy economist for CoBank. Genomics, the comparison of an individual animal’s DNA to the phenotypic performance of the entire population, reduced the generation interval with minimal loss in accuracy.

“Genomics has been the most important reason for improvements in milk, butterfat and protein production; cow health; and cow longevity,” Geiger adds.

While several indexes track genetic progress, Lifetime Net Merit (NM$) is the most universally implemented index across all major dairy breeds; it combines over 40 traits that consider production, health, longevity, feed efficiency metrics and confirmation into one measurement based on U.S. dollars, according to Geiger.

“The economic values are steeped in research, and a conservative $16.50-per-cwt milk price is used for the production traits,” he says. “The NM$ index is formulated by geneticists at USDA’s Animal Genomics and Improvement Laboratory and published by the Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding [CDBC].”

Under the progeny test system, the average genetic gain from 2000 to 2004 was $13.50 per year for marketed Holstein bulls.

“That means that with each successive year, the new crop of bulls would sire daughters that were $13.50 more profitable for the combined set of 40 traits than the previous year,” Geiger explains. “For various reasons, the gains from 2005 to 2009 — prior to and right after the introduction of genomics — moved up slightly to $36.90 per year.”

By 2010, just two years after genomic testing became commercially viable in the U.S., Geiger says that genetic improvement leapt forward, more than doubling from $36.90 per year to an $83.33 annual genetic gain from 2010 to 2022. That is a sixfold improvement compared to those years before genomics, or $70 in additional value per cow per year.

Great gains

“It’s important to note that these genetic gains are cumulative, as dairy farms routinely keep heifer calves from their cows for successive generations,” Geiger says. “With that in mind, the aggregate gain since 2010 would be $4.28 billion when calculating the full genomic impact. From a sustainability standpoint, this means the U.S. dairy industry needs fewer dairy cows with each passing year to supply the same amount of milk to serve the domestic market.”

To verify genomic predictions with real-world cow performance, Penn State University’s Chad Dechow plotted butterfat and protein production from Holstein cows in the pre-genomic and genomic eras. From 2000 to 2009, butterfat production improved annually by 0.46%, moving from 932 to 976 pounds per head for Holstein cows born in each respective year.

“The annual gain for butterfat production leapt to 1.75% annually in the genomic era, as actual butterfat production moved from 1,005 pounds to 1,216 pounds from 2010 to 2021,” Geiger says.

The same pace of change played out for protein production. From 2000 to 2009, protein yields in U.S. Holstein cows moved from 763 to 807 pounds, a year-over-year improvement of 0.56%. Genomics more than doubled gains at a 1.23% annual gain, as protein production moved from 821 pounds in 2010 to 942 pounds for cows born in 2021.

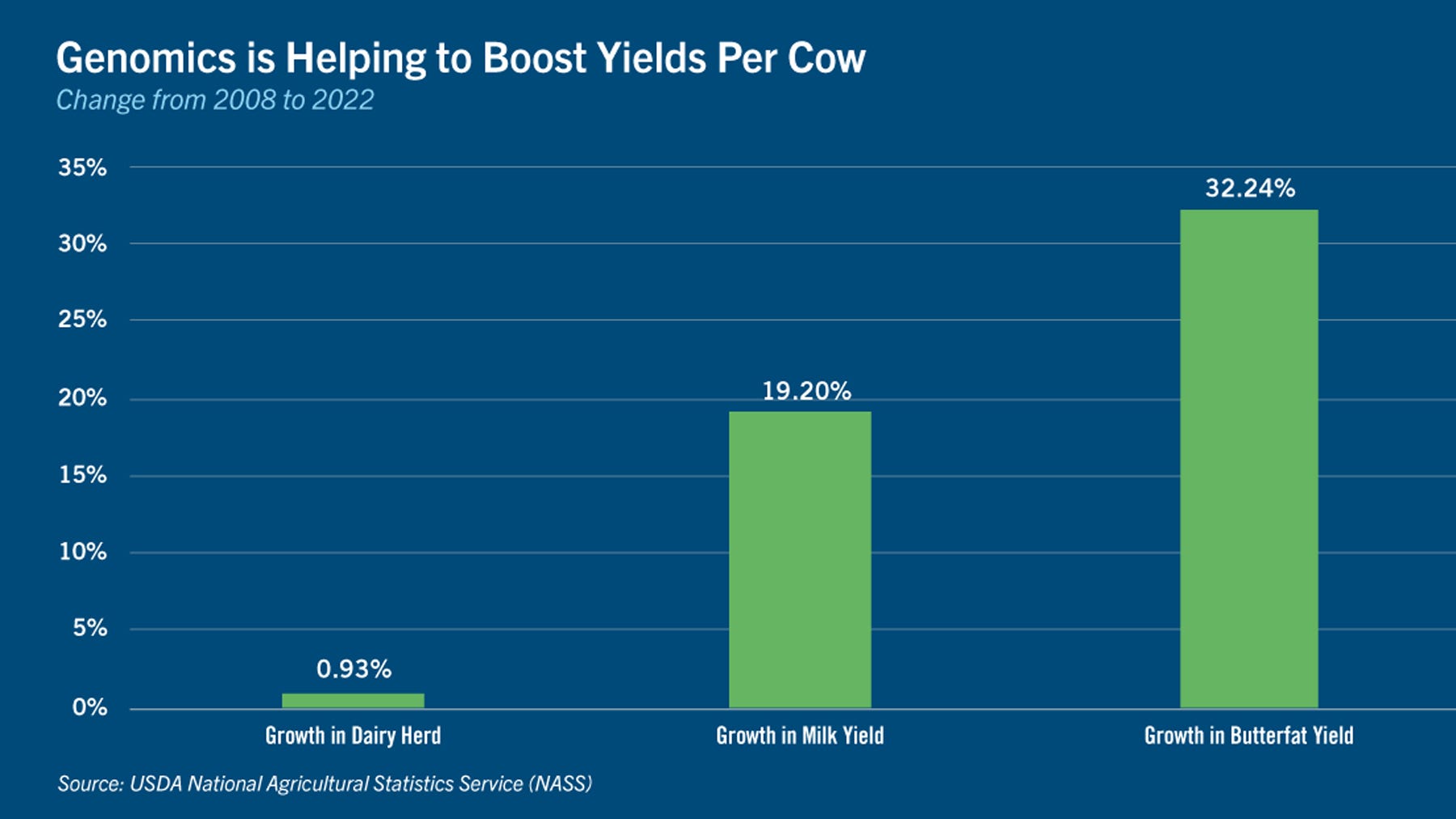

“When genomics started, the U.S. dairy herd had 9.3 million cows and has grown less than 1% some 14 years later. Yet the national dairy herd produces 19.2% more pounds of milk and 32.2% more pounds of butterfat than it did in 2008,” Geiger says. “Genetics has made a significant contribution, as has better feeding and cow care.”

The bottom line

While the sire impact has been tremendous, Geiger says genomic testing is starting to make significant inroads as more females get tested each year.

“It took seven full years for the collective U.S. dairy industry to run 1 million genomic tests from 2008 to 2015 through CDCB. Then it took another 26 months to run the second set of 1 million tests by July 2017,” Geiger says.

“It’s at this point that commercial dairy farms more fully bought into genomic science and started to test more heifer calves at birth to determine those animals that would make the best replacements by making the best use of resources. Those positive outcomes included less methane production, a reduced carbon footprint and less feed for each additional unit of milk,” he explains.

You can now read the most important #news on #eDairyNews #Whatsapp channels!!!

🇺🇸 eDairy News INGLÊS: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaKsjzGDTkJyIN6hcP1K