A new outreach program focused on farmers is missing something: farmers. But experts are determined to meet them wherever they are.

John Miller carries a red oak chair into the conference room at Union County’s civic center and places it beside a long table, where seven older men sit, carving wood. “This is a Franklin chair,” says Miller, 70, wearing a Gun Owners for Trump cap on his head and a hearing aid in his left ear. The men pause their carving—they’re making Li’l Abner boots under an instructor’s guidance—to look over his chair. Miller, a recreational hunter until his knees wore out, had driven home during class to retrieve it and share it with the group. “I made one for each of my daughters and one for my wife,” he says. Kyle Haney, rural health manager at the University of Georgia’s College of Family and Consumer Sciences (FACS), is the first to ask a question: “Is it named after Ben Franklin?”

“Well, he’s the one that designed it,” Miller answers.

Haney—a lanky man with a degree in mechanical engineering, and a 27-year-old in a roomful of men in their 70s—carries the quiet ease of a young adult accustomed to connecting with older people. For more than a year now, he has organized gatherings for men in Union County as part of a pilot program from UGA called Meet at the Shed, focused on farmers’ mental health. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, farmers can be up to twice as likely as people in other occupations to die by suicide. The meetings, where men gather to learn wood carving or woodworking, have attracted dozens of older rural men, a cohort also at great risk of dying by suicide. But, so far, no farmers.

Agriculture is the state’s largest industry, contributing more than 350,000 jobs and more than $74 billion to Georgia’s economy. With high risks and, often, thin profit margins for family-owned farms, social isolation, the vagaries of weather, and the burden of a multigenerational family legacy, the work can wreak havoc on mental health. According to a statewide survey from Mercer University, nearly a third of farmers in Georgia report thinking of dying by suicide at least once a month; 60 percent have thought about it in the last year. To combat this, a team from UGA has been reaching out to provide support—trying various approaches, from handing out fliers to organizing social events. But it’s proven difficult, says Diane Bales, a professor and extension specialist at FACS: “Farmers are sort of brought up to be independent and not ask for help.”

• • •

A 1908 article in the Macon Telegraph notes the first recorded suicide in Union County history: a 55-year-old man described as a “well-to-do farmer,” who owned 125 acres and was regarded as “one of the very best citizens of Union County.” He left behind a wife and several children. Today, Union County is home to more than 400 farmers and has one of the highest rates of suicide in the state, which is why UGA chose it for its first Meet at the Shed chapter. Farmers here and elsewhere are mostly male, older—in Union County, the average age of a farmer is about 58—and white, another group at higher risk for suicide. These men are at the central pressure point of several demographic groups—race, location, gender, age, and profession—most likely to die by suicide.

Often, financial solvency hinges on circumstances beyond a farmer’s control. Global market events and fluctuations in supply and demand affect sales and costs: The war in Ukraine caused a rapid rise in diesel oil prices, for example. Recent changes by the U.S. Department of Labor to the H-2A agricultural guest worker visa program helped farmworkers earn better wages but increased labor costs for farm owners. Those political problems aren’t new: In the 1980s, a corn and grain embargo against the Soviet Union, put into place during the Carter administration, caused prices to tumble and set into motion the biggest setbacks to farmers’ solvency since the Great Depression.

Then there’s the weather—which can devastate a crop or destroy a farm. “I can’t make it rain. I can’t make it not rain,” says Ginny Franks, a 63-year-old dairy farmer in Burke County. “I can’t make it not be a hundred-and-something degrees.” Tal Talton, 38, lost his family home last year when a tornado ripped through their Houston County farm, where he raises cows and row crops. Scientists predict more extreme weather events—such as droughts and heavy rainfall—as the earth warms.

Profit margins are frequently narrow for smaller farms. In the past, if farmers wanted to increase their profits, they might expand their footprint. That route, however, is becoming more difficult as they’re forced to compete with real estate developers, according to Haney, the rural health manager. “The farmer’s never going to be the highest bidder,” he says.

For two decades, the rate of suicide has been higher in rural areas than in cities, and that rate continues to rise. The stigma of seeking mental healthcare can be acute in these places, where there’s already a paucity of providers. Appalachia’s suicide rate is 17 percent higher than the country’s average. Following traditional social and gender roles with which they’ve been raised, men in rural areas coping with severe depression often believe they need to suffer in silence.

Miller, the woodworker, is a married father of three adult children and a retired schoolteacher and pediatric nurse. Today is his first visit to the Shed, and he doesn’t know any of the other men. Describing himself as a lifelong learner, Miller says the class is “something to do on a Saturday.” Across the table sits 79-year-old Tom Richardson; he and his wife of 56 years moved to Union County—to the county seat of Blairsville—a year ago to be closer to their adult son and his family. Richardson is an Air Force veteran and a regular at the Shed gatherings. Before he moved, “my garage was where everyone came to talk with me.” Here in Blairsville, “nobody comes down our street except FedEx and the mailman,” he says. “I really miss people.”

• • •

Jason Martin had no intention of joining the family business started by his grandfather in the 1940s. The 600-acre Martin Dairy Farm in North Georgia is home to 300 cows, which provide milk to a nearby processing plant. A couple of decades ago, his older brother, John, took over management of the farm, while Jason went on to serve as a youth pastor in Gwinnett County. Then John died by suicide. John was divorced, with a teenage daughter, and nearly a decade Jason’s senior. Their parents were in their 70s when it happened. “It kind of put the family in a very stressful position, so that’s when I decided that it would be best for me to come back to the farm and help figure out what to do next,” Jason says. “I had to process what was left behind.”

That was more than 15 years ago. Jason is now 46 and married, with children of his own. He still manages the farm in Bowersville, where twice a day—every day of the year—those cows need to be milked. Other chores: mix feed rations for milking and dry cows (pregnant or about to deliver), water and feed the animals, care for those that are ailing, deliver new calves, manage manure, monitor herd health and nutrition—and, depending on the season, prep, plant, or harvest fields. Since 2019, Jason has made multimillion-dollar investments in the business. He borrowed money to build an upgraded barn and become the second dairy farm in the state to use robotic milkers. He bought four of the machines, at about $250,000 each. Jason often worries that to ensure the farm’s future, he could have endangered it—that the debt he’s taken on might lead to the farm’s failure. “I’ve taken all that 70-something years’ worth of effort, and I’ve risked it all,” he says. Having witnessed the aftermath of his brother’s death, Jason never considers dying by suicide, but he’s honest about how tough running the business can be. How does he manage the pressure? “Some days are better than others.” Jason lives too far from Blairsville to participate in the Shed program there—he’s about a two-hour drive east—but he’s the type of farmer Haney would love to reach.

The inspiration for Meet at the Shed came in 2021, when a team at UGA read U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy’s 2020 book, Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World. In a section entitled “Lonesome Cowboys,” Murthy chronicles the emergence of the Men’s Shed movement, which began in Goolwa, a small river community in Australia, and has since spread to the U.K. and the U.S. The motto for the U.S. Men’s Shed Association is “Men don’t talk face to face. We talk shoulder to shoulder.”

“It occurred to me that one reason for the men’s shed movement’s success is that it doesn’t require men to admit they’re lonely,” Murthy writes. Nothing in UGA’s Meet at the Shed promotional fliers mentions mental health. “We had always been very cognizant of this stigma surrounding suicide and mental health, and very intentionally chose stress as a much less pejorative term and one that people could speak about more comfortably,” says Anna Scheyett, a professor at UGA’s School of Social Work.

Miller, who intends to return for future gatherings, says he was raised to be stoic. “That’s the way guys were taught: ‘Keep your feelings to yourself. Otherwise, you’re weak.’” This mindset can exacerbate the social isolation that sometimes happens later in life. Murthy writes that, because the vast majority of Americans do not live in multigenerational households, aging can be a chapter of life when their peer group dwindles and their risk of loneliness begins to rise.

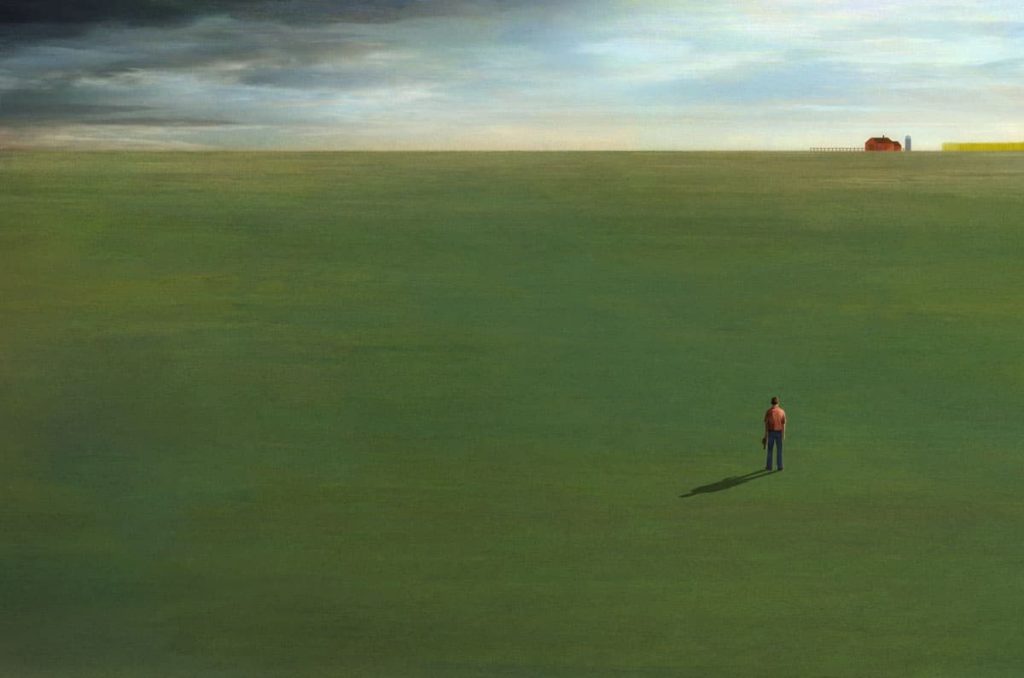

PHOTOGRAPH BY ALLISON SALERNO

Haney has spent hours advertising Blairsville’s Shed events, chatting up pastors, posting fliers in feed stores, placing ads in the North Georgia News, and posting on Facebook pages. A farmer himself, he understands the constant demands of the job: “Having the time to get out of the farm and do stuff is a big thing.” (Ginny Franks, the dairy farmer in Burke County, last took a vacation—for two days—in July 2018.) “Even once they do retire, it’s hard to break that cycle,” Haney explains. Now, more than a year into Meet at the Shed, he’s been encouraged by the program’s robust attendance: “In a rural community, so many people are connected through each other. If we prevent one suicide, we ultimately could be helping to reduce that impact for others.” But the goal is still to reach farmers.

In the U.S., midwestern states—Minnesota and Michigan, in particular—have led the way in studying and attempting to alleviate farmer stress. “We’ve been learning from them,” Scheyett says, citing a program funded by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture that pays for therapists to make house calls to farmers. UGA’s Institute for Integrative Precision Agriculture is working to map risk factors in real time in order to gauge where rural stress may be highest. The idea would be to target resources, such as mental health professionals trained to work in the community, as a kind of mental health rapid response team.

In April, Governor Brian Kemp signed a bipartisan bill that seeks to conserve farmland. So far, the legislature has not funded the program. Across the U.S., if farmers agree, in perpetuity, not to sell their land to developers, the federal government gives them half the money they would have earned had they sold the land for commercial use. Once Georgia’s program is funded, the state will join 29 others that currently offer money to help pay the other half.

During the pandemic lockdowns, Scheyett, the UGA professor, taught herself to weave; she compares her efforts to reach farmers with her new hobby. “Rather than thinking about programming, for me, it’s thinking about weaving,” she explains. “How do you make it a thread in the cloth, in the fabric of the community?” Last fall, in focus groups with farmers’ wives across Southwest Georgia, Scheyett learned that they would welcome information like how to manage their own stress, how to tell when stress is dangerously high, and who in the community they can call for help. “You need snippets of information in places [farmers] already are,” she says. Farmers’ wives often provide much of the emotional support for their husbands, so UGA hopes to reach them too, at new social events designed for them. Still, at the Meet at the Shed kickoff a year ago, rural women showed up—but no farmers’ wives.

Last October, Jennifer Dunn was hired as the state’s first rural health agent. She focuses on 41 counties in Southwest Georgia and uses production meetings hosted by the UGA Cooperative Extension to connect with farmers who might be in psychological distress. Farmers need to attend those meetings, in which agents talk about the latest fungi or about drought concerns, to be able to use pesticides on their crops; it’s a kind of continuing-education credit. Dunn’s work began with the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities after Hurricane Michael devastated the state’s pecan crops in 2018, because officials were concerned about the emotional toll the crop’s failure might have on farmers. Since then, she has expanded her outreach from meetings in three southwest counties to 11. Ultimately, Dunn hopes to train therapists to be rural health agents in other regions of Georgia.

She approaches the topic of mental health indirectly at the production meetings, which generally attract between 30 and 100 farmers, mostly men. A county health department employee is on hand to offer free blood pressure screenings and begin conversations about how stress impacts the body. Then Dunn, who was raised on a cotton and pecan farm, introduces herself and has a quick, five-minute chat with the farmers about the pressures they might be feeling. “First I say, ‘What stresses you guys out?’” she says. It’s usually the weather and their finances. Next, she’ll ask, What do you do about it? They say they drink. And pray. They joke about how sex is a good stress reliever. She tries to ensure they have a support system: a pastor, a significant other, a therapist, even a fellow farmer.

Finally, tucked into folders the county extension agent passes out about pesticide use is a flier about emotional health. “I sneak it in there,” Dunn says, along with her phone number. Although most men don’t follow up, Dunn knows they see it. Recently, after a meeting, a 67-year-old farmer approached her and said, Who would’ve thought that y’all cared enough to ask?

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or visit 988lifeline.org to speak with a trained crisis counselor any time of day or night. The State of Georgia also offers a toll-free call center for individuals to access services, 24/7. The number for the Georgia Crisis and Access Line is 800-715-4225.