It’s considered a staple by most households but has become a subject of much angst as the price in supermarkets has pushed ever higher and become increasingly unaffordable.

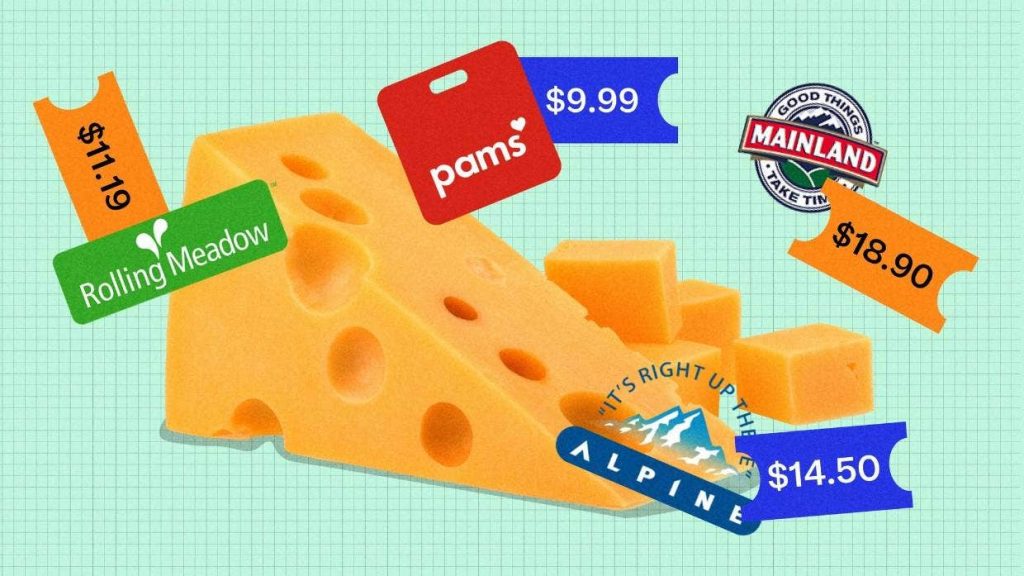

According to the latest food price index data for February, the average price for a 1kg block of mild cheddar cheese in the supermarket was $14.13.

That’s the third-highest level on record, behind January’s record $14.56 and December’s $14.44.

We are told that local prices in New Zealand are set by the global market.

But cheese prices on the Global Dairy Trade platform have fallen back to July 2021 levels. Back then, Stats NZ data shows the average cheese price was $11.08, although inflation has since been running hot.

Consumer NZ says it’s really hard to know if shoppers in New Zealand are paying a fair price for cheese at the supermarket.

“We have consistently heard from Fonterra that the price we pay for dairy is set by the global dairy trade – so when the global price drops, we expect the price we pay should drop too,” says the consumer watchdog’s communications and campaigns manager Jessica Walker.

“No doubt it is more complicated than that with multiple factors to consider but it’s our view that Fonterra should not be taking advantage of global price drops to the detriment of shoppers here.”

Still, Fonterra says that it’s not getting the profit margins in New Zealand that it gets elsewhere. The company recently wrote down the value of its domestic consumer business by $92 million, saying it had not been able to raise prices as quickly as its costs were increasing, putting pressure on margins.

The head of the local business, Fonterra Brands New Zealand managing director Brett Henshaw, says its wholesale cheese price, which is what supermarkets pay, is influenced by global dairy commodity prices as well as the cost of making the finished products including labour, packaging, energy, manufacturing, storage and distribution.

“Global Dairy Trade (GDT) prices can be volatile, which is why we always take a longer term view when determining our wholesale prices,” he says. “When there’s a sustained change in GDT prices or other input costs we can expect that these will flow through to our wholesale prices eventually.”

But he notes that supermarkets set retail prices at their own discretion.

ANZ agricultural economist Susan Kilsby says there is a correlation between GDT prices and what the supermarkets pay for cheese, but there’s often a big lag because the supermarkets buy their cheese on longer term contracts, rather than week-to-week based on GDT prices.

The price for end consumers also depends on competition and how retailers choose to set their pricing, which will influence whether consumers see any changes or not, she says.

“Generally with cheese prices coming back in the international markets, you would expect at some point to see some softening in prices at the supermarkets but there would tend to be quite a big delay in that coming through,” she says.

“The general trends over a longer time and sort of smoothed out will flow through, but it doesn’t mean we’re going to see lower cheese prices next week.”

Kilsby says she can’t comment on whether prices were being passed through appropriately because she doesn’t have access to the data around pricing.

Supermarkets in New Zealand are dominated by two large groups, Foodstuffs, which owns Pak ‘n Save and New World, and Countdown. The Commerce Commission found the duopoly could be making $430m a year in excess profits.

Foodstuffs last year commissioned economics consultancy Infometrics to produce a monthly Grocery Supplier Cost Index which measures the cost of more than 60,000 grocery products from its suppliers. But both Foodstuffs and Infometrics say they can’t provide data on the cost of cheese.

Rival Countdown also says it can’t provide data on the cost of cheese from its suppliers as it’s commercially sensitive. A spokesperson suggested speaking with suppliers and producers.

Neither Synlait nor Goodman Fielder responded to a request for comment.

“Retail price setting is opaque in New Zealand – there could be a number of parties clipping the ticket, including Fonterra and the duopoly,” says Consumer NZ’s Walker.

“Consumers are vulnerable because it is so hard to know what a fair price is.”